Rohan Amerasinghe is one of the senior, but lesser known Sri Lankan artists whose work has always been about ‘politics’. He is a self-taught artist; a personality that claims an artist’s identity outside of Colombo’s art hierarchy which is constructed by the Faculty and Art graduates from the IAS (Institute of Aesthetic Studies, currently the University of Performing and Visual Arts). He has been actively participating in Colombo’s art scene since the mid 1970s. He is a regular participant in the annual art exhibition organized by the Art Council of Sri Lanka, and many a time his work has been rejected by the selection committee of this state sponsored show, for its explicitly radical nature.

A regular presence at various exhibitions in Colombo, he is an avid ‘culture buff’ and a latter day bohemian, who makes his presence felt at a multitude of art and cultural events. Despite his long and keen, and at times combative association with Colombo’s art scene, the art community has been lukewarm towards his art. As such, he is still not acknowledged as a mainstream artist.

A regular presence at various exhibitions in Colombo, he is an avid ‘culture buff’ and a latter day bohemian, who makes his presence felt at a multitude of art and cultural events. Despite his long and keen, and at times combative association with Colombo’s art scene, the art community has been lukewarm towards his art. As such, he is still not acknowledged as a mainstream artist.

For us, Rohan Amerasinghe presents a prelude of sorts for the 90s Trend. His importance as an art personality relies on his contribution to the contemporary or late modernist aspects of Sri Lankan art.

The purpose of this short essay is to endow Rohan Amerasinghe’s work with some historical weight, by positioning his art and artistic personality in the uncertain terrain that emerged at the modern/late modern interstice of the late 20th century art of Sri Lanka.

Noticeable aspect

Sri Lankan modernist art reached an important turn in the early 1990s. The artistic trend that gathered momentum in the early years of the1990s is now named the ‘90s Trend’. The most noticeable aspect of the 90s Trend during its early years was its preoccupation with issues pertaining to violence and political crimes, although it acquired so many other avenues and paths of expressions in later years. Consequently, some critiques of the 90s Trend called it the ‘trauma school of art’. Nevertheless, what I would like to emphasize here is, that taking violence and social injustice as points of reference for art making is not the sole purpose of the 90s Trend. But, what needs to be underscored is that Sri Lankan modernist art already had a well established tradition of art making that had a political interventionist edge. However, this particular tradition was not as strong and popular as the bucolic and meditative trends of 20th century modernist art. This politically interventionist art tradition, which was an important sub tradition within the modernist discourse, could not develop to its full potential. It did not develop a relevant body of aesthetics that had the potential to define a paradigm shift in art within the modernist framework. The major achievement of the 90s Trend is to energize this political interventionist art tendency into a fully blown art movement with its own theoretical parameters of aesthetics.

Even among artists of the 43 group who averted any direct expressions of violence and social injustice in their art, one can see sporadic attempts at recording and responding to events of violence, though in an indirect manner. One such example is, George Keyts’ ‘Bhima and Jarasanda (1943)’, which depicted the violent clash between two epic heroes from Mahabharatha. Ivan Pieries’ painting of the raid of Colombo during World War II (Easter Sunday raid, 1943-42) is another example of this nature. However, during the 1960s and early 1970s, the Sri Lankan art scene was not marked with any significant art with any reference to violence or socio-political issues worth mentioning. But, by the late 1970s, after the first JVP uprising and the violent social environment that emerged in the country, one can see the emergence of 3 artists whose work had a socially interventionist stance. The most popular and the best known of the three, S.H. Sarath, a graduate of the IAS, did a series of drawings on social injustice and violence, which were well received by the art audience of the late 1970s. Wijayakulathilake, a participant in the 1971 youth uprising, served a prison sentence and consequently, became a painter while in prison. Wijayakulathilake’s painting on violence and social injustice also acquired sufficient attention from the art audiences of the late 1970s. However, one cannot say the same of Amerasinghe. He remained largely obscure until the 1990s. The reasons for this are many. The most obvious reason is, he could claim no link with the IAS and therefore, remained an outsider to the art community, largely without the endorsing and supportive network of IAS.

Sarath is a graduate of the IAS, and Wijayakulathilake married a graduate of IAS while he was still imprisoned. Both Sarath’s and Wijayakulathilake’s painting styles had roots in the then established stylistic norms that came from the IAS, while Amerasinghe’s style was and still is totally alien to that.

Narrative artist

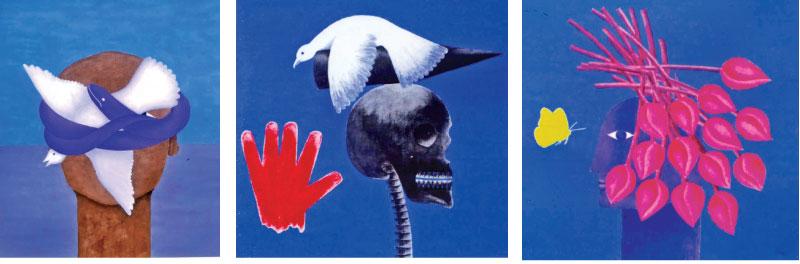

Amerasinghe’s artistic personality, I would argue, stands apart from the other two in several important ways. Unlike Sarath and Wijayakulathilake, who as artist-personalities critique the ‘establishment’ only through their art, Amerasinghe confronted the ‘establishment’ both through his artwork as well as through his personality as an artist! While both Sarath and Wijayakulathilake are classical modernist, in terms of ‘art thinking,’ Amerasinghe was never so. He has always been consciously a narrative artist: He always has a ‘story’ to tell which is more or less, issue based. He has never been concerned with expressing a ‘feeling’, or a ‘mood’. As can be seen in his work, he has never attempted to achieve a state of ‘sublime’ in a modernist sense. His story and his restlessness are very much located in the ‘now’ and ‘here’. This aspect of Amerasinghe’s art and artistic personality are the factors that make him an important artist in the transitional phase of 20th century Sri Lankan art, from modern to late modern periods. In many ways, he and his art pre-figured basic tenets of the 90s Trend. This allows us to consider Rohan Amerasinghe as an important and serious contemporary art personality.

Amerasinghe, characteristically is a very vocal personality. He has a magnetic attraction to pick up arguments and quarrels that can become long drawn debates on the meaning and function of art, artist personalities and art establishment. He engages in these quarrels/arguments in such a vocal manner as if he is demanding the attention of society. But, he has always been, in many ways, a loner with a very loud ‘monologue’.

- Jagath Weerasinghe.