Kelani Palama (The Kelani Bridge) written by the late R.R Samarakoon is a play which can surely be called a modern classic of Sinhala theatre; born on the stage at the juncture Sri Lanka opened its doors to the policy of an open economy, in the late 1970s. On Sunday, August 27, Kelani Palama came alive on the boards of the Punchi Theatre in Borella, and was performed to a near full house, which shows that this is a work of theatre which still draws a good audience.

The theme of the work deals with the plight of the urban poor who inhabit shanties or slums, along the banks of the Kelani River, beneath the Kelani Bridge. When the monsoons unleash floods, the residents of the slums become squatters on either side of the bridge’s pavements, which is the only (relatively) safe high ground they can occupy to escape the flood waters. This is a story that depicts the pathos as well as the hardiness and resilience of the poor folk who continually become temporarily displaced people, virtually destitute due to acts of nature as well as the inaction of the State. The latter of the two forces - the State (or government) provides no durable solution to the annual assail by flood waters which leave the homes of the shanty dwellers wrecked as well as endangering their lives and disrupting their livelihoods. Their repeated appeals for suitable land/homes to reside in, away from the danger of floodwaters are never answered. A problem said to date back decades and left unanswered by every successive government.

The action unfolds around the neighbouring ‘shelters’ (erected unlawfully on the bridge pavement) of ‘Chutte’, his wife Matilda, their son Saranapala, and of Martin and his new bride Rupawathi. The story brings out the frustrations of the affected people and the indignities they are made to suffer at the hands of hypocritical bureaucrats and politicians. This is also a story about how people in that stratum of abject haplessness strive to move up the social ladder. The prime example being Saranapala who reviles his socio-economic station, and at the end finds that the way to overcome it is by joining the very forces of the State that oppressed them.

The play contains doses of comedy as well as laughter of a ‘dark vein’. I did at several junctures wonder if laughter was in fact the proper response to some situations shown on stage, like for example, the way in which the displaced flood victims are marshalled to receive bread rations as food aid from the government. Comedy is built into the performance through (the) manner (of acting) and (tone of) language. Yet, one cannot help but wonder if in fact the segment of people depicted in this play would provide something of a comedic spectacle in the types of situations found in Kelani Palama. But then, the art of proscenium theatre must be acknowledged as predominantly a space of/for the segments in society who are not abjectly impoverished. This is not particular to Sri Lanka but very much the same, the world over. And, Kelani Palama as a work of theatre contains that undeniable vein of being a creation which is of and for ‘people not from slums’, but about slum dwellers.

The character of Saranapala, to my understanding, works as a symbol of centre-rightwing ideas. The work as a whole appears to carry a left oriented visage, as it decries government as a machinery of the affluent. And, for the likes of Chutte, it may be said, he can be viewed somewhat as the ‘stateless man’. The whole lot of them in fact through the narrative show that their ilk is the officially enfranchised but practically disenfranchised part of a nation. They are at best on the fringe of society hoping the centre will cast a genuinely empathetic look upon them, and actuate durable solutions to their unanswered problem. It is in effect a play that seeks to catch and reflect a glimpse of society’s intentionally neglected periphery, to eyes that lie in closer proximity to the centre.

A notable feature when it comes to the language brought out in this work is that it is not replete with course expletives generally perceived as characteristic of the speech of the urban slum dwellers. It is therefore, from a conservative standpoint more apt for a middle class family audience. However, the counter argument to this point may be the question as to how authentic a representation of the urban slum dweller does for the language of this play?As a reviewer, on this matter I make no judgements of my own, but shall simply present two sides to view this particular facet of the narrative.

Another notable facet of the stylistics in the dialogue in Kelani Palama is that it is colourfully expressive with metaphor and turns of phrase. This facet shows a strong dose of folk wit and wisdom through idiomatic language. One may almost feel at times that what is heard from Chutte and his like is like a dialect of its own.

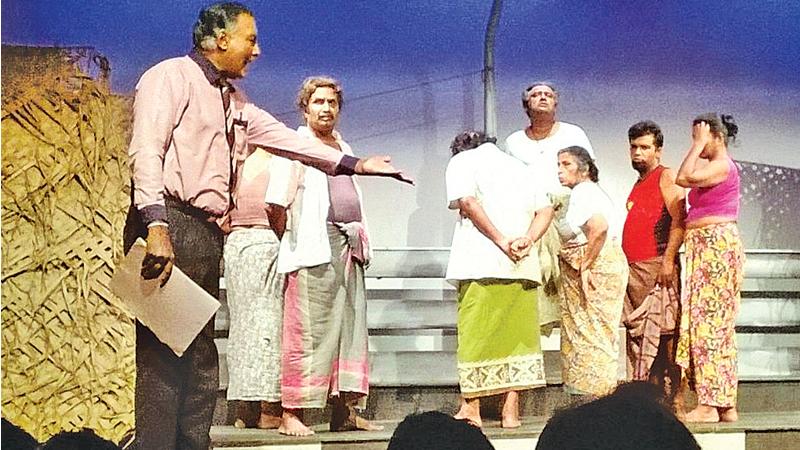

The costumes and makeup of the production were commendable. The set design too was appreciable and effective in depicting the temporary shelter/shacks put up on the bridge’s pavement. On the acting front, the character of Saranapala was played compellingly by veteran actor Prasad Sooriyarachchi. Renowned actor Palitha Silva who delivered a formidable visage of the near indomitable Chutte, did at times fumble with his lines which caused momentary but noticeable ripples in the fabric of performance.

Seasoned actress of the screen and stage Ramya Wanigasekera who has been playing the role of Chutte’s long suffering dutiful wife Matilda, since Kelani Palama was first staged in 1978, delivered a praiseworthy performance. I would unhesitatingly say that despite the odd hiccup here and there in the delivery of lines, the performance went off well overall.

The cast and production team of Kelani Palama must be applauded for providing theatregoers an opportunity to watch this modern classic of Sinhala theatre, which will hopefully carry forward its strong message to another generation.