3 December, 2017

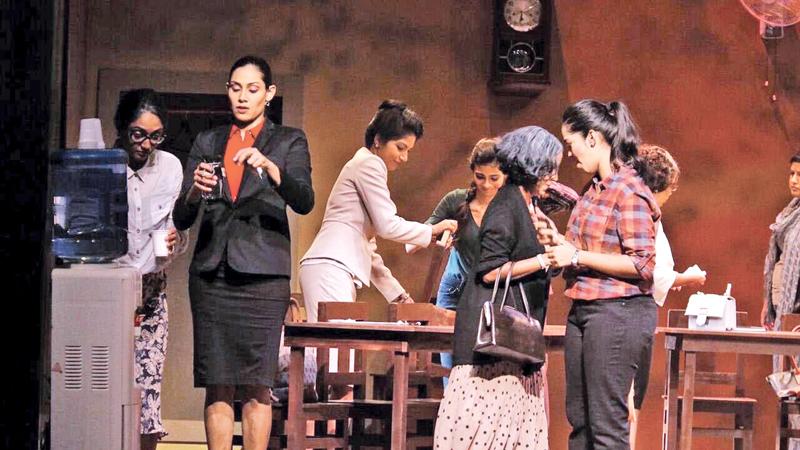

On November 19, the boards of the Lionel Wendt auditorium came alive with the Cold Theatre 7’s production 12 Angry Women based on U.S playwright Reginald Rose’s script 12 Angry Men. The gender switched rendition/version of Rose’s script has been tried and tested in the West but was a first for theatregoers in Sri Lanka, presented as a production directed by Kevin Cruze performed through special arrangement with The Dramatic Publishing Company. The cast of female thespians who came on stage that evening consisted of Neidra Williams, Celina Cramer-Amit, Shanuki De Alwis, Nadishka Aloysius, Sashya De Alwis, Shania Smith, Saranie Wijesinghe, Bimsara Premaratne, Mokshini Jayamanne, Kavitha Gunesekera, Liza De Costa, Piorina Fernando and Mayanthi De Silva. And yours truly was seated under the gentle darkness of the Wendt that evening occupying seat Q-7 as an observant reviewer.

The basic scenario of Rose’s story is uncomplicated. Twelve jurors must deliberate on the innocence or guilt of a teenager accused of killing his father. At the very outset eleven jurors are certain of the boy’s patricidal guilt, and the dissenting juror speaks out of ‘a reasonable doubt’. Gradually, through the dissenter’s resolve to go beyond what is taken for granted by the majority ‘as the obvious’ the whole jury rethinks the case and admits a ‘reasonable doubt’ which results in the boy’s acquittal. Although what seems a simple scenario made up of dialogue narrated in a single room, what makes Rose’s script a complex wrangling of perspectives and perceptions is how both logical reasoning and impulsively emotional reactions are made to collide and finally find conciliation.

The basic scenario of Rose’s story is uncomplicated. Twelve jurors must deliberate on the innocence or guilt of a teenager accused of killing his father. At the very outset eleven jurors are certain of the boy’s patricidal guilt, and the dissenting juror speaks out of ‘a reasonable doubt’. Gradually, through the dissenter’s resolve to go beyond what is taken for granted by the majority ‘as the obvious’ the whole jury rethinks the case and admits a ‘reasonable doubt’ which results in the boy’s acquittal. Although what seems a simple scenario made up of dialogue narrated in a single room, what makes Rose’s script a complex wrangling of perspectives and perceptions is how both logical reasoning and impulsively emotional reactions are made to collide and finally find conciliation. A nameless collective

A significant feature of this script is that not a single juror is identified to the audience by a name. They are in effect a nameless collective whose inner complexities cannot be merely framed into the mark of a personal name. It is in a way an exercise of gauging personas of individuals based on how their inner selves are portrayed for individuality. There lies, to my understanding, the principal task of the director when dealing with this dialogue heavy, one act play. Every one of the twelve jurors needs to get projected with a clear impression of their individual worth in the collective, through their separate persona. In effect, the concept behind Rose’s script presents a case of (observable) behavioural psychology or behaviourism, through the medium of theatre. And the most pressing factor to keep in mind when dealing with Rose’s script is that it is related to an aspect of the criminal justice system. Thus, an approach of realist theatre is what optimizes realizing the crux of this script.

What Cruze presented as his vision of 12 Angry Women, being directed and designed by him (as per official credits), was a work of mixed media. The ‘stage play’ 12 Angry Women was flanked by two screenings of cinematic scenes of what goes on in the courtroom, both prior to the jury’s deliberation and afterwards. One may even raise the question as to what type of director is Cruze in relation to this work? Stage drama director? Film director? Or both? Tracy Holsinger had screen presence but no stage thespian function. She acted as the judge who was visible in the video/cinema narrative/element. Was she a member of the cast? In that case, which cast exactly? She certainly can’t count as a member of the cast of the ‘stage play’. There was in my opinion too much cinema fused to Cruze’s craft of giving Rose’s ‘story’ a ‘narrative form’.

A nameless collective

The impression I got of the finale which was ‘cinema’, reinforced this opinion to my senses. The last moment on the stage, where parting glances are shared by the characters played by Bimsara Premaratne and Shanuki de Alwis couched in sombre light and ominous music that tastefully built a ‘dramatic effect’ was denied the chance for an end worthy of theatre due to the closing cinematic element that followed. The judicial pronouncement screened as a scene of cinema was in my opinion an utter superfluity that did more of a disservice to the effort(s) of theatre in this production, in the attempt of delivering ‘completeness’ to ‘a courtroom story’.

Stagecraft and costumes were very well done and deserve commendation. On the acting front there was no clearly visible symmetry of talent, but did not mean the performance wasn’t enjoyable. However, I honestly felt some of the characters like the juror who grew up in the slummy tenements, should have been better utilized. One of the fates that can befall less prominent characters in a sizable ensemble is being relegated to near oblivion in the flow of action run by a host of dynamic figures, unless their moment in the spotlight is crafted to effectively project to the audience their central purpose in the play. The juror who grew up in the slums, played by Celina Cramer-Amit, is an introverted character whose principal worth comes out in sharing her personal knowledge about how a switchblade knife is handled. That was a key moment that Cruze failed to capitalize on, and that juror’s presence and contribution appeared underplayed and merely incidental.

The acutely analytical juror in a skirt, wearing spectacles, played by Nadishka Aloysius had gesticulation and enunciation that made her performance somewhat a ‘theatrically cued persona’. Her function as a strongly analytical perspective provider was clear, but the persona was made to seem mechanical and monotonous. An analyst doesn’t have to appear being near robotic in demeanour. Yet another character Cruze could have crafted better to achieve plausibility.

Bimsara Premaratne was not the most pronounced persona among the dozen but that also adds to show the subtlety with which the first dissenting juror manages to set the ball rolling to turn the tables without being an ‘imposing persona’. Through this measure Cruze demonstrated good judgement on the effectiveness and need for tact in the sort of contentious situation that the jurors are found, and how diplomacy and empathy work when the odds are painfully against a sole dissenter who refuses to follow the herd.

Kavitha Gunasekera, who played the smug and overbearing juror coloured with notions of class war, outshone the rest. Gunasekera was simply brilliant, and at times mesmerising. She was consistently in gear when steering her character through the fluctuations in emotion, actions and the politics that brewed between the twelve women, delivering her shifts in tone and demeanour convincingly through the dynamics of interplay with characters as well as individual moments of commanding the spotlight for herself.

Behaviourism in action

As I mentioned earlier, Rose’s story of twelve bickering jurors deals with behavioural psychology. How do we, the audience, gauge the psychology of the jurors based on their behaviour, keeping in mind that they are tasked with arriving at a verdict which partly involves gauging the psychology of the accused and the witnesses based on what behaviour they could observe of those persons. The concept of Rose’s story (theoretically) revolves around the objective of giving ‘the people’ a chance to see the aspect of the court system that does not happen in ‘open court’, which is jury deliberation. The play is in some respects a discreet window to a space that the public is barred from entering. The politics of this play is very much a critique of the criminal justice system on the matter of ‘transparency’ to ascertain exactly how a jury arrives at its verdict, especially, when the life of a fellow citizen hangs in the balance. The closer a realist theatre approach is adopted for this script, the more ‘true to life’ the situation of a jury in deliberation becomes to the viewer.

Misplaced creativity

Cruze adduced elements that performed the function of ‘glazing for glamorizing’. The first of these was a freeze moment of the players following the secret ballot that revealed a second dissenter that tilts the original status quo. The lights dimmed and a spotlight flashed from one juror to the other, designed as a device for dramatic effect and ‘whodunit’ intrigue. It was, in my opinion, a juvenile gimmick.

If performed to achieve the prime objective, this script provides the means to understand what goes on in the minds of the jurors at every juncture in the narrative through their dialogue and physical behaviour. Their acting is the ticket to create an image of what may be going on in their heads. Cruze spliced the space of the jury room and broke away from the depiction of behaviourism when ‘mimed scenes’ of the murder were infused on the stage to depict what the jurors ‘may have visualised’ in their heads while dialogue recollects what the jurors were told in court of how the murder was believed to have been perpetrated. The infusion of that nonverbal element in the attempt to give visual effect to a mental aspect of the jury’s thought process broke the dimension of time and space in which the ‘action of the jury’ was situated. One may argue that it creatively broke the monotony of seeing twelve jurors and their actions within a confined space. While it can no doubt be accepted as demonstrative of creative theatre craft, I believe it was misplaced creativity.

The heart of the story is a critique of the criminal justice system with its adversarial argument based method and the practice of being judged by ‘one’s peers’, that unfolds in designated official spaces as courtrooms and jury rooms, defined by physical reality. Rose’s script is about facing and dealing with the monotony, the menace, and the jarring tensions that cannot be escaped in the process of reaching justice. In attempting, or pursuing, ‘spectacularity’ through visual dynamism, Cruze diluted the depth of what Rose’s script about a contentious jury in deliberation is meant to (re)present to society. The twelve female jurors may have acquitted the nameless teenager charged with murder, but Cruze killed Rose’s script.

Pix: Shehan Fonseka