Getting farmers to prepare land with the first rains, not waiting for irrigation water, will improve efficiency in agriculture, where rice yields are among the highest in the region and chemical use not as high as believed, a senior scientist says.

Policymaking based on science, not myth, and better co-ordination among decision-makers on using water for irrigation, drinking and electricity generation will help mitigate effects of drought, says Buddhi Marambe, Senior Professor of the Department of Crop Science, University of Peradeniya.

Policymaking based on science, not myth, and better co-ordination among decision-makers on using water for irrigation, drinking and electricity generation will help mitigate effects of drought, says Buddhi Marambe, Senior Professor of the Department of Crop Science, University of Peradeniya.

“Sri Lanka’s agriculture was in very bad shape and now is in the recovery stage, rather than the growth stage,” Prof. Marambe said, delivering the 26th annual S. R. Kottegoda Memorial Oration at the Sri Lanka Association for the Advancement of Science (SLAAS). Kottegoda was a former president of SLAAS and Dean of the Medical Faculty of Colombo University.

“What went wrong was not because of climate change or natural disaster but because of a man-made disaster – poor decision-making – at a time when we were trying to ensure food security,” he added.

“In June 2021, the government took an unscientific decision and banned the two most important agricultural inputs – synthetic fertiliser and synthetic pesticide – amid criticism from all corners.

“The decision was changed in November 2021, seven months later – but we are still experiencing its repercussions with Sri Lanka even now at the recovery phase.”

If the country can quickly recover, with policy decisions based on science, not superstition or myth, then it can move into the growth stage.

An academic of the Department of Crop Science of the university’s Faculty of Agriculture, Prof. Marabe whose research interests include weed science, climate change adaptation, and food security, spoke on reviving Sri Lanka’s agriculture sector.

“My most important recommendation, especially to those starting paddy cultivation in the ‘Maha’ season, is to ask them to start preparing their lands in time with the onset of inter-monsoon rains, and not wait till reservoirs start releasing water,” he said.

“If not, it is a waste of rain water. The timing of cultivation is important – we need to get across this message.”

Preparation of land is the time of the highest water use, which is why scientists recommend doing it with the least amount of time and maximum use of rain water.

Preparation of land is the time of the highest water use, which is why scientists recommend doing it with the least amount of time and maximum use of rain water.

Water use planning is done by the Water Management Panel of the Mahaweli Authority’s Water Management Secretariat which decides how water in hydropower reservoirs and irrigation tanks is used for irrigation, drinking and electricity generation.

The Water Management Secretariat also has said it is essential for farmers to prepare their land in a short time using rainwater as much as possible.

Four rainy seasons

Sri Lanka has four rainy seasons. The two monsoons, South-West from May to September in the wet zone, and North-East, from November-December to March in the dry zone, come in-between two inter-monsoonal periods, from March to April, and from October to November, when convectional and cyclonic rains occur.

The Maha or main cultivation season is from September to March, when most of the island’s agricultural areas get rainfall from the North-East monsoon. The Yala or minor cultivation season is from May to August, when rice is grown with other field crops based on availability of water.

Difficulties in managing bulk water allocation arise when some farmers start cultivation late or over-cultivate, even though the decision on exact dates to start and end the cultivation is discussed during the Water Management Secretariat’s biannual meetings.

Although Sri Lanka is considered to have no water scarcity within the country, and per capita, water availability is enough to cater for the estimated peak population, studies show there are water shortages in certain areas and at certain times, especially during drought periods.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), Sri Lanka’s water stress is already at 90.8 percent, which means that the country is consuming 90.8 percent of its total available renewable freshwater resources at present apart from environmental needs, and is therefore categorised as “highly water stressed”.

He said better co-ordination among decision-makers in water use planning can help mitigate the effects of drought and competing demands for water.

Recent rains the island experienced came with the re-activation of the tail-end of the South-West monsoon whose withdrawal from peninsular India began in late September.

This year, when farmers were to harvest, drought affected yields, while soon after harvesting they got hit by rain when drying paddy.

“The only way out is through proper planning,” he said. “Things are not going in favour of Sri Lanka regarding its food security. More water means trouble and less water also is trouble.”

He cited the agitation for irrigation water from the Samanalawewa reservoir by farmers in the Uda Walawe basin as an example of how better co-ordination could have reduced crop losses.

Regulated water supplies

In early July farmers began asking for Samanalawewa, managed by the Ceylon Electricity Board only for hydroelectricity generation, to release water to Uda Walawe reservoir, used for irrigation only.

Water was released from the hydroelectricity dam only in late July owing to concern that drawing down the Samanalawewa reservoir might lead to power cuts in the south.

The problem could have been solved had there been early co-ordination between the Agriculture Department, Irrigation Department and the CEB, he said.

According to the Water Management Secretariat, Uda Walawe reservoir now receives regulated water supplies from Samanalawewa reservoir.

Uda Walawe accounts for almost a quarter of the extent of paddy damaged by drought islandwide.

Despite this loss the Agriculture Department estimates 2023 rice production will be adequate to meet the island’s needs.

Farmers were more attuned to changes that could affect agriculture as it was not only a matter of their production capacity but of their livelihood, he said.

Farmers were among the first to protest against the sudden ban on synthetic fertiliser and synthetic pesticide that led to sharp falls in production of paddy, maize and manufactured tea in 2022.

“Farmers knew it much more than us given the time they spend in paddy field and on tea plantations,” Prof. Marambe said.

The struggle between understanding myths versus facts had always been an issue in Sri Lanka, with many people relying on superstition rather than looking at scientific evidence.

Prof. Marambe highlighted three myths that had led to the downturn in agriculture.

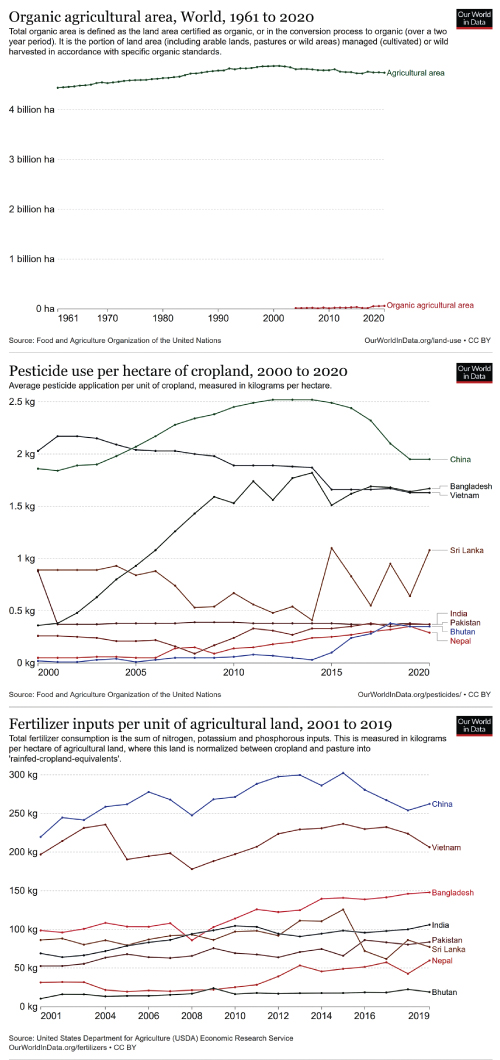

One was that the whole world was moving towards organic agriculture and away from synthetic fertiliser and pesticide. The other was that Sri Lanka uses the highest quantity of fertiliser among South Asian countries. The third was that Sri Lanka has the highest level of pesticide use among South Asian countries.

Global crop cultivation is still increasing, given advances in crop science and animal science, he said.

Fertiliser use

Agricultural land area is about five billion hectares, or 38 percent of the global land surface, while organic agricultural land area is a mere 72.3 million hectares, according to the FAO.

“There’s nothing wrong with organic agriculture,” Marambe said. “But FAO studies on use of fertiliser on different continents show that in all cases, use of fertiliser has been increasing over the past 20 years.”

Sri Lanka also does not have the highest level of fertiliser use in South Asia, with Bangladesh, India and Pakistan using more than the island, and fertiliser use even higher in China and Vietnam.

“We’re not a heavy user of fertiliser. We’re still at a very low level,” Prof. Marambe said. “Sri Lanka, even after using quite a low amount of fertiliser in paddy cultivation, still has higher productivity than Bangladesh and India.

Vietnam and Japan are ahead of us. Most farmers there cultivate one season. We cultivate two seasons and make the soil infertile.”

Use of pesticide has also been increasing on all continents except Europe, where it has dropped marginally, by 0.2 percent, since 1999, according to the Pesticide Atlas of 2022.

Sri Lanka’s use of pesticide per hectare of cropland is not the highest in South Asia, with Bangladesh above the island, as is China and Vietnam.

“I’m not trying to create a better picture of pesticide but to present the reality – because we have been taken for a ride – to help us make judicious decisions to improve agriculture,” he said.

In paddy cultivation, Sri Lanka’s average paddy yield before synthetic fertiliser and pesticide were banned was 4.5 metric tonnes a hectare, while India still cannot break above four metric tonnes a hectare. India’s total production is more mainly because of the sheer extent under cultivation.

“Productivity-wise we have shown how productive our lands are and how good our scientists are,” he said. “People ask what has the Department of Agriculture done over the years, assuming they’ve done nothing.

“Different types of Nadu and Samba rice varieties, like ‘Keeri Samba’, which everyone is consuming, were developed by our own scientists. We do not import paddy. All seeds are from Sri Lanka.

“We do not have hybrid rice in Sri Lanka. The new high yielding varieties introduced since the 1960s were through normal breeding programmes by our own scientists, that ensured the yield of paddy keeps increasing.”

In the 1940s, the average paddy yield in Sri Lanka using traditional varieties and technology was only 650 kilograms a hectare and in 1950 only 1.65 metric tonnes a hectare. By 2021, using new improved varieties, the yield had risen to 4,670 kg a hectare.

Risks

Sri Lanka usually imports only special varieties of rice like Basmati and Thai jasmine rice which tourists demand. China, the world’s biggest rice producer, also imports rice, as does India, the biggest rice exporter.

But in 2022, the island’s paddy production fell by 34 percent after synthetic fertiliser and pesticide were banned, requiring the import of 783,000 MT of rice for $292.5 million, at time when the country needed foreign exchange very badly.

The risk of having to rely on rice imports was highlighted when India, which accounts for 40 percent of the global rice trade, banned export of non-basmati white rice in July 2023, sending rice prices up by 15-25 percent.

“So if we do not have our own rice, we would be in trouble in trying to import rice,” he added.