The influence of Kung Fu cinema on the world has been nothing short of profound. Originating from the rich tapestry of Chinese Opera and Taoist philosophy, the genre has not only provided audiences with exhilarating action sequences but also served as a powerful vehicle for cultural expression and national pride. Spearheaded by legends such as Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, Kung Fu cinema transcended borders and inspired a global fascination with Chinese martial arts and Eastern philosophy

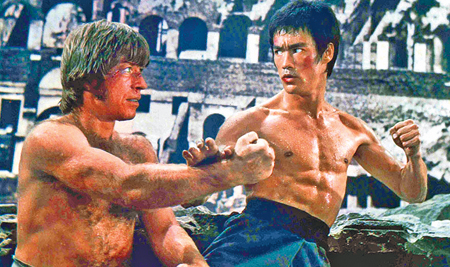

Bruce Lee vs Chuck Norris in Way of The Dragon (1972)

The fighter enters the scene. He is surrounded by thugs and goons, but he is not the prey. The camera pans close and he scans his surroundings like a ferocious tiger. One thug rushes at him with a bat and with one swift kick our hero sends him flying into a stack of garbage cans. The fight is on, but the fighter handles all the villains with the gracefulness of a crane and the power of a dragon.

Seems like a generic scene from a Kung Fu film that audiences have grown to love, but there is so much more than meets the eye. The Kung Fu film genre has its origin in Traditional Chinese Opera and has fingerprints of Taoist philosophy. In a time where the Chinese people were reeling from their ‘Century of Humiliation’, Kung Fu movies uplifted their spirits in a huge way and just as much as America exported ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll’ to the world, the Chinese projected the allure of their culture through martial adventures brought to the silver screen.

What is Kung Fu Cinema?

Master Yip Man faces off against Karate fighters in Yip Man (2008)

Kung Fu cinema is a film genre that primarily focuses on action-packed sequences involving martial arts techniques. It originated in Hong Kong in the 1960s and gained international prominence during the 1970s and 1980s. Kung Fu Cinema typically features elaborate and highly choreographed fight scenes, often showcasing various forms of Chinese martial arts such as Wing Chun, Tai Chi and Shaolin Kung Fu, among others.

Kung Fu movies as we know today were pioneered by greats such as Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan. The emergence of the kung fu genre in Hong Kong marked a deliberate departure from the fantastical elements of contemporary Wuxia films. During that era, known as Shenguai Wuxia, filmmakers blended supernatural fantasy with traditional martial arts themes.

Wuxia and Kung Fu films have their origin in Chinese Opera. Even today, the most famous names in Kung Fu cinema were trained in Chinese Opera schools. Chinese Opera gave a foundation for the martial arts film genre that blossomed in Hong Kong and inspired many of the early Kung Fu films that dramatised the lives of folk heroes such as Fong Sai-Yuk and Wong Fei-Hung.

The Dragon enters

Tea house shooting from Hard Boiled (1992) starring Chow Yan Fat

However, the Hong Kong movies of the 1960s were mostly escapist Wuxia fare. They were period films with dramatised plotlines and colourful costumes highly inspired by Chinese Opera.

But this all changed with Bruce Lee who introduced an explosive style of on-screen fighting and presence. “Bruce understood cinema, the art and entertainment value,” says Billy Wong, a veteran stunt man and Kung Fu actor. Lee had roots in Chinese Opera (his father was a famous Chinese Opera actor), martial arts through his teacher – the legendary Yip Man and his experience as a young street fighter in the tough streets of Hong Kong.

Lee was a renaissance man for the world of Kung Fu. Wong said that Bruce taught martial arts to foreigners, something his Chinese peers frowned upon. “Lee was innovative. Back then, movies didn’t have a lot of extras. But in his first film ‘Big Boss’ Lee insisted he can fight a large number of opponents instead of just three or four bad guys and this has since become a staple in Kung Fu cinema,” he said.

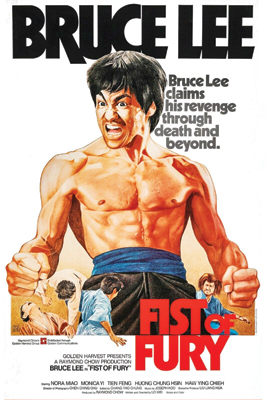

Fist of Fury (1972)

Unlike Wuxia counterparts, kung fu producers emphasized authentic hand-to-hand combat over reliance on elaborate special effects, shunning the use of animation in fight sequences to appeal to a different audience base.

But Bruce Lee’s influence didn’t stop there. His career effectively broke down racial barriers for Asian actors in leading film. Lee also tried to introduce his philosophy behind his fighting style Jeet Kun Do (Way of the Intercepting Fist) into his film but with little success. “The scene from ‘Enter the Dragon’ where Bruce holds up a finger pointing to the moon wasn’t understood among non-Chinese viewers who found the conversation funny. Same in Fist of Fury where a technique called ‘Regrouping of Strength’ was seen as showboating but it is actually a pause from intensive fighting. Bruce also tried to teach his philosophy in his film ‘Game of Death’, which he planned to be his magnum opus, but he passed away before the project could be finished,” Wong said.

Although Lee couldn’t teach Chinese philosophy through his movies, his various interviews, his fighting style and charisma inspired a generation of young martial artists and so many others to pursue the profound wisdom of Eastern philosophers.

National pride

During the mid-20th Century, Kung Fu movies were not just entertainment; it gave the Chinese people everywhere an immense sense of national pride. From the occupation of Hong Kong by the British in the so-called ‘Century of Humiliation’ to the Japanese invasion of China during World War Two, the Chinese people felt crushed in more ways than one. In this situation, Kung Fu movies such as ‘Fist of Fury’ and ‘Way of the Dragon’ that showed a proud Chinese protagonist trouncing Japanese Karate masters and Westerners using Kung Fu was a morale boost, an projected Chinese strength to a global audience at the same time.

Chinese Opera – ‘Farwell my Concubine’

It gave the Chinese people so much self-respect and an element of soft power in a world that had looked down upon them for so long. Subsequent Kung Fu movies followed this nationalist formula for a time but it became overplayed; the Yip Man series is a prime example.

But as the situation in Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan changed during the turn of the century, so did taste. In Hollywood, the Kung Fu genre became a novelty as movies either paid homage or lampooned the classic martial art fable with movies such as Kill Bill I &II and Kung Pow: Tongue of Fury.

Just like Wuxia before it, the reception of Kung Fu films went into decline apart from the general reception for films starring superstars such as Jackie Chan and Jet Li. In China, audiences were starting to draw to gritty crime dramas such as Police Story and Election.

Later, Wuxia films also made resurgence with titles such as Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon breaking box office records. During the late 80s and early 90s, the genre itself experienced a rebirth with directors such as John Woo who rehashed the weapon brandishing flair of Wuxia films and the high paced action of Kung Fu films into a new genre called Gun Fu. John Woo’s Gun Fu films such as A Better Tommorow and Hard Boiled redefined Hong Kong cinema and replaced the righteous martial artists of the 70s with flawed, anti-heroes who solved their problems with guns, lots of guns and explosions.

This post Kung-Fu era of John Woo’s Gun-Fu went on to inspire Hollywood which produced classics such as the Matrix movies and video games such as Max Payne which redefined entertainment as we know it.

Chinese Opera

Bruce Lee during a 1971 interview where he explained his famous ‘Be Like Water’ philosophy

The influence of Kung Fu cinema on the world has been nothing short of profound. Originating from the rich tapestry of Chinese Opera and Taoist philosophy, the genre has not only provided audiences with exhilarating action sequences but also served as a powerful vehicle for cultural expression and national pride. Spearheaded by legends such as Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, Kung Fu cinema transcended borders and inspired a global fascination with Chinese martial arts and Eastern philosophy.

Its impact extended beyond mere entertainment, serving as a beacon of empowerment and resilience for the Chinese people during challenging historical periods. Despite evolving tastes and shifting cinematic landscapes, Kung Fu cinema’s legacy endures through its transformation of action sequences and storytelling, influencing subsequent cinematic genres such as Gun Fu and impacting the broader entertainment industry, including Hollywood and video games.

As we reflect on the dynamic trajectory of Kung Fu cinema, its enduring legacy reminds us of the power of storytelling, cultural expression and the universal appeal of the indomitable human spirit, resonating with audiences worldwide. It continues to stand as a testament to the timeless allure of martial arts, the spirit of resilience and the unyielding pursuit of excellence.