Writers do often censor themselves. It was Arundhati Roy the embattled Indian author who once stated that if somebody doesn’t write something, there is always a reason for him or her to keep it all under the hat.

The quote cannot be found, but the words were to that effect.

The quote cannot be found, but the words were to that effect.

Though this writer doesn’t agree with Roy on many things, he does agree with her on this one. If a writer or journalist refuses to write something, it’s for a reason.

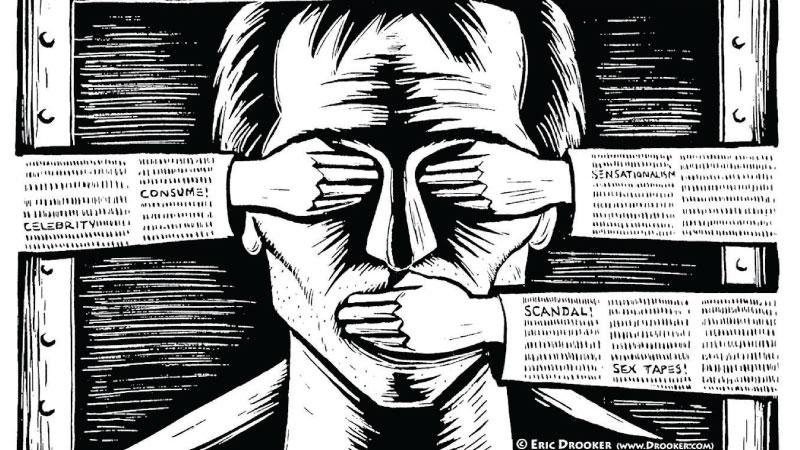

He or she fears probably that they’d be thought to be beyond the pale. Of course in many countries journalists or opinion makers don’t write on certain issues, because they fear State or State-aided reprisals.

That’s the common form of self-censorship. But as Roy implies folk out there censor themselves for various reasons, and sometimes it’s to avoid friendly fire.

They feel societal mores may just not allow them to write about what they want at the given moment. They’d rather that their best ideas die, than they die of embarrassment. Think Gajaman Nona in more reticent and retiring an incarnation.

But the best works of writers are often the ones they don’t make public and won’t write down at all. It’s good for writers to be able to recognise that.

It’s good for anybody engaging in any original pursuit to recognise that. The best inventions are ahead of their time. It’s cliché now that the experts who appraised Thomas Edison’s crude light bulb had said that the invention is interesting but would never be of any gainful use to anybody, and would as a result be commercially unviable.

BUSHEL

But the cliché and what’s known needs no repetition here. What fresh demons may newly imperil creative impulse these days? Well, it’s social media for instance. Social media has spawned a new breed of moral-police and in some instances the herd opinion has made it extremely difficult for writers to challenge whatever the orthodoxy that’s currently taken as gospel.

The best work of writers has a history of being frowned on due to prevailing orthodoxies. This goes for other creators of original work such as dramatists and movie-makers as well. When Ediriweera Sarathchandra was assaulted by the goons pledging allegiance to the then Government of JR Jayewardene in Sri Lanka, there was no social media in this country or anywhere in the world, but they still demonised the man as a retrogressive influence, and proceeded to maul him.

But ideas that are censored today or are deliberately kept under a bushel by the writers themselves, will often become prescribed reading in the future. Ulysses by James Joyce was banned even before its’ official release in both the UK and the USA, but is now prescribed reading in many school and university curricula.

But what’s more interesting than the banning and censorship itself is the dynamic behind writers behaving as if they know they would face social or State-sponsored opprobrium or some other form of disapproval from powerful sections of society.

Writers for instance may fear that they would be labeled conspiracy theorists and be cancelled on that score. There are many conspiracy theorists of course who have peddled theories because they can get maximum media traction as a result, and such folk have earned whatever social isolation that may be their fate.

There is the infamous Alex Jones who says that the Sandy Hook school shooting in which 26 persons including children died due to random gun violence, was in fact tragic-theatre staged by actors.

No self-respecting writer would want to be classed with Alex Jones who has given journalism and broadcasting a bad name with his brand of storytelling. But when there are genuine people who want to tell a real story that are afraid of revealing the truth because they don’t want to be classed with the likes of Jones, that’s a tragedy.

When Erin Brokovich began exposing instances of groundwater contamination in Hinkley California which led to residents being afflicted with mysterious illnesses, she was considered a pesky conspiracy theorist at best.

But she didn’t mind being cast as a nuisance and didn’t give up on her campaign. This led to lawsuits that resulted in one of the biggest payoffs to citizens by any commercial concern accused of polluting the environment.

The problem is that many Brokovich types don’t want to come out with their exclusive expose lest they be branded conspiracy theorists. But some outlandish sounding stories turn out to be true though they may sound conspiracy narratives to people who live in their comfort-zones and hear these stories for the first time, out of the blue.

The Iran-Contra affair in the U.S was dismissed when first reported in the 80s, as a conspiracy theory. In short the then administration under the presidency of late Ronald Reagan sold weapons to Iran on which an arms embargo had been imposed, and then channeled the funds realised through these sales towards funding insurrection against a leftist Government in Nicaragua.

Rumours

Norman Mailer, American novelist and journalist claimed at the time there were rumours circulating about the Iran-Contra affair, that it takes too long for the Fourth Estate to come up with crucial exposes due to the various pressures brought to bear on investigative journalists to make sure that all aspects of their stories are credible.

At a birthday party in his honour he said in view of this situation of journalists being hamstrung by systemic flaws, there ought to be a special unit that’s given the authority to investigate State actors flouting the law.

Basically, he meant that journalists were afraid of being branded conspiracy theorists and didn’t want to come up with crucial, game changing stories because they’d be accused of not having the iron-clad evidence. But eventually, after a revealing plane-crash and other events it was apparent that the Iran-Contra ‘conspiracy theory’ was no theory at all and was indeed the plain truth.

This sort of writer-reticence is not confined to investigative journalism alone. Also, the syndrome is not confined to writers. Inventors and other creators are afraid of coming up with product-ideas fearing they would be laughed at and made out to be lunatics or worse.

But, both the laptop computer and the automobile were derided initially as quirky and idealistic inventions that would however serve no practical purpose.

The experts at that time said cars could never be manufactured economically enough to make them affordable and marketable to the public. Experts on technology said that nobody would want to use a laptop because they’d rather use a newspaper for news and crossword puzzles rather than ‘lug that thing around.’

But the laptop became a far more streamlined, sleek gadget than most people at the time thought it ever could be, and the rest is history. Those who challenge prevailing orthodoxies are always mocked, and it seems, the more useful their ideas are the more intense the mocking will become.

Writers and other creators should remember this verity that the exact story they are too shy to come out with is probably just the one that is waiting to be told. Granted that sometimes writers would suppress their own idea because it just isn’t the time to reveal the truth. That’s if they are sure the reaction would disrupt their lives to a point where things would become intolerable for them.

But sometimes it makes no sense to keep your best work under a bushel, or your best idea or your most groundbreaking revelation under a veil of secrecy of your own making.

But it’s a tough decision to make. Creators and inventors as writers and journalists, have to live with the reaction to their work essentially on their own. There is little comfort in the fact that certainly over time they would be proven correct, the way the automobile went from being ‘certainly too expensive for mass marketing’ to everybody’s preferred mode of transportation.

But at least the thought of being proved correct one day should be a spur or some sort of minimal motivation at the very least, to launch a challenge on the orthodoxy. Most trailblazers were definitely shy before they decided they’d rather be bold than cagey.