– Part 1

This article seeks to define the scope of the concept of equality and the rule of non – discrimination and its international legal regime.

This article seeks to define the scope of the concept of equality and the rule of non – discrimination and its international legal regime.

The reference to the UN Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) in particular and other international instruments adopted by the ILO and UNESCO would be made in this study in examining the norms and standards set for the guarantees of equality and non – discrimination and for the obligations of the State in this regard.

As the welfare State of modern times moves into its stride, there is scarcely any aspect of activities the law does not take within its province. It is, perhaps, impossible to visualise even a fraction of such activities being accomplished without the aid of law. The concept of equality is no exception. This move has increased the indispensability of the law for the regulation of activities in the public interest.

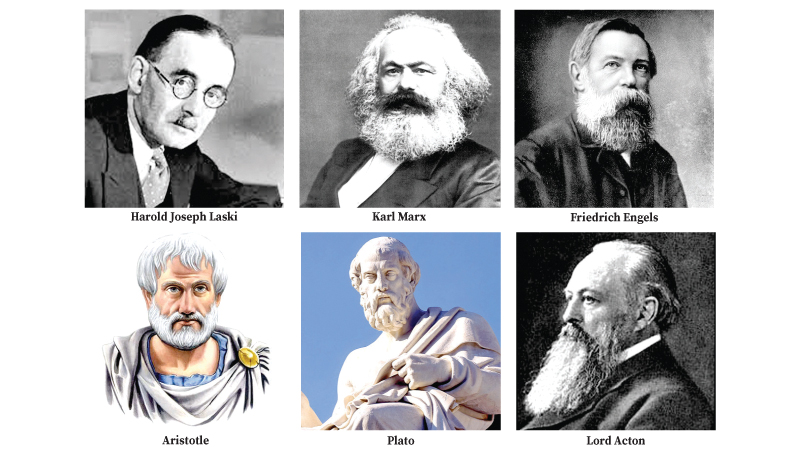

The concept of equality has an ancient history. Aristotle analysing the concept of justice emphasized the close relationship between justice and equality. He divided justice into two parts, namely, general justice and particular justice. In the general sense, it meant equality. He made a further division of particular justice into two namely corrective justice and distributive justice. While corrective justice aims at redressing an equality which has been interfered with, distributive justice, on the other hand, aims at an equal distribution of the social good among persons equal before the law.

Prof. C.G. Weeramanthry states that despite the 23 centuries that have elapsed since Aristotle wrote his Nichomachean Ethics, his formulation still remains, perhaps, the most influential single piece of writing on the concept of justice, which emphasizes the close relationship between justice and the concept of equality. How equality is determined is a matter for which philosophical speculation can give no answer by itself. Rousseau is a key proponent who discussed the nature – convention distinction with regard to rights. Engels viewed the modern demand for equality as something different from its ancient idea: that is all men have something in common and to the extent are also equal. As Engels emphasized, “The equality of nations is just as essential as the equality of individual.”

Harold Laski emphasizes that equality does not mean identity of treatment. This is because there can be no identity of treatment as long as people are different in words and capacity and need. He viewed equality as having two aspects, namely the absence of privilege and adequate opportunities are opened to all. He noted inequalities of wealth as a source of inequality. He added that without virtual economic equality, the attainment of freedom is impossible and political equality is never real.

Marx and Engels considered that inequality is the result of class divisions which are unjust but historically necessary. They are finally alterable in a classless society. According to them, the idea of equality is a historical product as much as inequality was historically necessary. Marx saw class equalisation as “impracticable nonsense” and called for abolition of classes to achieve social equality.

Equality and rule of law

The rule of law has a number of different meanings. A primary meaning is that everything must be done according to law – that people must be governed by laws and not by the arbitrary commands and dictates of rulers and their officials. People are entitled to the protection of equal laws, applying equally to rulers and their officials who enjoy no special privileges or exemptions.

Another meaning of the rule of law is that government must be conducted under a framework of recognised rules and principles which restrict the discretionary powers of public bodies and officials: absolute or unfettered discretions cannot exist where the rule of law reigns. Consequently, whenever the law confers powers or discretions on public bodies and officials, those powers are treated as having been conferred on them in the public interest; and not for private or political benefits; such powers are held in trust for the people, must be exercised for their benefit; and they must be exercised lawfully and fairly and not arbitrarily or unreasonably.

The concept of rule of law has been subject to various interpretations. According to Dicey, the rule of law has three meanings:

(i) The absolute supremacy of regular law as opposed to the influence of arbitrary power.

(ii) Equality before the law or equal subjection of all classes to the ordinary law of the land administered by the ordinary courts of law.

(iii) With the British, the laws of the Constitution are the consequences of the rights of individuals as defined and enforced by the courts.

While today Dicey’s definition is not accepted in full, the relationship between the rule of law and equality as expounded by him is still valid. In fact, a major element of the rule of law is equality.

Equality and equity

In its origins, equity was based on natural justice and naturally enough the principle which were enunciated as lying at the heart of the system also display an affinity with the same theme. These guiding principles are the foundation upon which equity has been built as known as the maxims of equity in their form they are not older than the 18th century though their origins are generally more ancient. But they conveniently set out the policies followed by the English Courts exercising equitable jurisdiction.

One such maxim is that “equity will not suffer a wrong to be without a remedy”. This maxim lies at the very root of the equitable jurisdiction for it was the failure of the English common law courts to provide a remedy in certain cases that led to eventual emergence of the Court of Chancery.

Another important maxim is that “equity follows the law”. The intention and purpose of the equitable jurisdiction is to supplement rather than supplant the jurisdiction of the English courts of common law. Equitable interference occurred only where the common law was ineffective and the situation demanded remedy. From this, it followed that equity would not attempt to disturb common law rule which had been laid down with all due deliberations. If the common law had already taken all the relevant circumstances into account, equity would not interfere.

Equity has always been concerned with the question of balance, demanding that if equity is to apply, and equitable remedies are to be granted, the parties should be in “equal” positions whereby one does not possess an advantage over the other. Our 1978 Constitution, for example, provides in Art 126(4) dealing with FR jurisdiction of Supreme Court that, “Supreme Court shall have power to grant such relief or make such directions as it may deem just and equitable in the circumstance in respect of any petition or reference.”

Equality and justice

Justice, the most elusive of man’s ideals has been the subject of an unending quest. Among the early thinkers making an attempt to introduce some analytical element into the discussion of justice were the Greek philosophers. Plato saw justice as a relation among individuals depending on their social organisation. Aristotle too discussed this concept of justice. He distinguished between the general justice and particular justice. In the general sense, justice was the sum of all the social virtues. In the particular sense, it meant equality.

Within the particular justice, he saw a further division between corrective justice and distributive justice. It is a distinction which has enjoyed general importance in all discussions of justice since then.

Corrective justice aims at redressing an equality which has been interfered with: punishment, compensation and restitution would be obvious examples. Distributive justice, on the other hand, aims at an equal distribution of the social good among persons equal before the law. Despite the 23 centuries that have elapsed since Aristotle wrote his Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle’ formulation still remains, perhaps, the most influential piece of writing on the concept of justice.

Prof. Rawls said his conception of justice in the form of two principles: (1) that each person participating in a practice or affected by it has an equal right to be most extensive liberty compatible with a like liberty for all; (2) that inequalities are arbitrary unless it is reasonable to expect that they will work out for the greatest benefit of the least advantaged and the positions and offices to which they attach, are open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity.

As Prof. Rawls said, these principles express justice as a complex of three ideas – liberty, equality and reward for services contributing to the common good. Rawls’ work has already generated a vast volume of discussion, partly because it represents a point of confluence of justice theories of the past, partly for the originality and freshness of his approach. Difficult though it is to define, the ideal of justice still stands before all legal systems as a constant inspiration.

Equality and liberty

The concept of equality which is central to the discussion of justice lies at the root of the democratic idea. Many great revolutions aimed at shaking off arbitrary rule of one form or another have stressed this concept of equality. The question arises whether increased equality can only be achieved at the expense of liberty or conversely, whether expanding liberty must diminish equality. Learned opinion is divided on this matter.

On the one hand, it is clear that a certain degree of liberty is necessary to promote the ideal of equality. For example, to achieve economic equality in a society, a measure of liberty is necessary. Lord Acton, one of the outstanding thinkers on the concept of freedom, emphasized that equality unrestrained could destroy freedom. There are examples of these revolutions such as French, Russian and Chinese.

Concept of right to equality

This section deals with various aspects of the concept of equality and its application in a broad perspective. Human beings by nature are of unequal strength, talent and other attributes and are clearly not units of equal weight in their societies. The inequalities of nature are reinforced by the social and economic circumstances which as people commence life, place some at an advantage over others. As people move on, numerous factors acting singly and in combination, favour some and disadvantage others. As the myriads of constituent units of a society keep thus shifting their positions relative to each other, absolute equality among them even in one characteristic or for a moment of time is patently an impossibility. Far greater is the impossibility of preserving general equality for any period, however short. A permanent state of equality is only the remotest dream.

Equality before law and equal protection of law

There are two famous legal expressions linked to the concept of equality, namely (1) all persons are equal before the law and (2) all persons are entitled to equal protection of the law. The expression “equal protection of the law” is found in the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution. Article 18 of the 1972 Constitution of Sri Lanka embodied both phrases. The Indian Constitution in terms of Article 14 also uses both expressions.

Article 7 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights contains both expressions. Article 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights also embodies both aspects of the concept of equality. It is also praiseworthy to note that jurisprudence on the aforesaid aspects have been immensely enriched by our Supreme Court by way of Judicial Activism in exercising in particular, its FR jurisdiction.

Equality before the law is the negative aspect implying the absence of any special privilege in favour of any individual and the equal subjection of all classes to the ordinary law. Equal protection of the law is a more positive concept and implies equality of treatment in similar circumstances. Jennings finds equality of treatment to be part of the principle of equality before the law. However, it is impossible due to the claims of society itself and of public interest to have absolute equality among all classes. Thus, foreign sovereigns and diplomats are entitled to certain immunities. The second expression of the concept of equality, equal protection of the law is the positive aspect of the concept and means that persons similarly situated should receive similar treatment by the law, both in rights and duties. To be continued next week.