Some stories may feel haunted and haunting, even if they are not ours. Such stories bring heaviness to our hearts. Holocaust literature is one genre that is not just about facts and figures. It’s a genre born from the ashes, overflowing with one chorus of voices whispering tales of unimaginable horror. Every story takes us to the depths of human suffering, the enduring fight for understanding, and, most interestingly, the power of memory.

Dr Anne Kalpf

The Holocaust is a disturbing chapter in 20th-century history, period. Not even the most atrocious word in any English dictionary can adequately convey the intensity of that era.

In his submission to the Journal of Social Philosophy, titled Holocaust Literature as a Genre, Gerald Levin argues that the historical development of most genres is frequently overlooked in discussions.In essence, he challenges the idea that once a genre is established, understanding its historical evolution becomes less important. Levin specifically addresses the oversimplification of Holocaust literature, which is commonly defined by its subject—the destruction of European Jewry, widely termed Auschwitz. The genre is not only determined by its subject matter but also by its distinctive form.

Levin brings in Elie Wiesel’s statement, which suggests that a novel about Auschwitz may stand against conventional definitions. This results in a reconsideration of boundaries and expectations placed on literature dealing with history – particularly traumatic events.

Literary layers

The genesis of Holocaust literature dates back to the post-World War II era. Diaries and journals of survivors laid the foundation for this literary genre. The initial writers were firsthand witnesses to the Holocaust. Their lives were marked with helplessness and incomprehension. Their works, which came to be known as Holocaust literature later on, offer a voice to the inexpressible horrors the Jews endured as a national group.Holocaust literature gradually evolved into an exploration beyond survivors. The later works came to be written by authors who didn’t experience the Holocaust firsthand. That said, Holocaust literature can be considered a genre with layers.

Holocaust Memorial Day (HMD) is observed every January 27 to commemorate the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest Nazi death camp. At the core of HMD’s mission is to remember the six million Jews who perished during the Holocaust, alongside millions killed under Nazi persecution of other groups. The significance of Holocaust literature in this collective endeavour serves to understand the depth of human suffering. Literature enables the voices of those silenced by genocide. It offers narratives that humanise the victims. It continues to provide future generations with a deep understanding of one man’s unchecked bigotry.

Holocaust Memorial Day (HMD) is observed every January 27 to commemorate the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest Nazi death camp. At the core of HMD’s mission is to remember the six million Jews who perished during the Holocaust, alongside millions killed under Nazi persecution of other groups. The significance of Holocaust literature in this collective endeavour serves to understand the depth of human suffering. Literature enables the voices of those silenced by genocide. It offers narratives that humanise the victims. It continues to provide future generations with a deep understanding of one man’s unchecked bigotry.

The significance of any literary genre must not be confined to its ability to convey historical facts. The narratives that voice the helplessness of genocide victims must have the capacity to bring readers close to uncovering the deeper nuances of what the very survivors want future generations to comprehend. These narratives, in that sense, preserve the collective memory of the Holocaust and its impact on individuals.

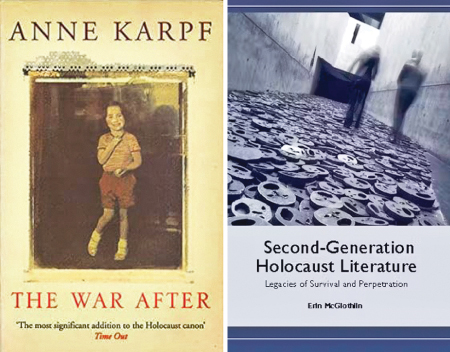

In her book titled Second-Generation Holocaust Literature, Erin McGlothlin separates a distinctive perception: the second generation. This generationdid not directly experience the Holocaust but is very much affected by it. McGlothlin expands the interpretation of second-generation literature, which constitutes not only the perspective of survivors’ children but also the children of Nazi perpetrators.

Identical themes

Central to McGlothlin’s focus is the literary legacy of both groups within the second generation. Her work investigates how these writers employ almost identical themes of stigmatisation to give expression to their complex relationships with their parents’ histories. This exploration of familial connections is often layered with silence and unspoken burdens. Yet they provide a unique lens. The impact of the Holocaust echoes across generations through that lens.

Central to McGlothlin’s focus is the literary legacy of both groups within the second generation. Her work investigates how these writers employ almost identical themes of stigmatisation to give expression to their complex relationships with their parents’ histories. This exploration of familial connections is often layered with silence and unspoken burdens. Yet they provide a unique lens. The impact of the Holocaust echoes across generations through that lens.

A central theme in McGlothlin’s analysis revolves around the emergence of anxiety regarding signification within the structure of second-generation literature. The texts she scrutinises bear the marks of ongoing aftershocks from the Holocaust. It reveals the struggles faced by the second generation with the traumatic legacies passed down to them.

McGlothlin’s analysis spans nine literary texts from American, German, and French authors, providing a cross-cultural examination of the second generation’s literary response to the Holocaust. The book opens with the narrative of Dr Anne Karpf, who, as the child of parents who lived through the Holocaust, was raised in postwar England.

Karpf’s narrative in The War After: Living with the Holocaust (1996) provides a window into the challenging situation faced by the second generation of Holocaust survivors. Karpf describes her dilemma when she fell in love with a non-Jewish man, a situation that is directly at odds with her parents’ attempts to preserve the family’s link to Jewish tradition. Eventually, her struggle with these competing claims manifests itself physically as a severe rash:

I tried repeatedly to reconcile these warring views until, eventually, it all extruded through my hands, unerring somatic proof (the body being an incorrigible punster) that I couldn’t in fact handle it. Beads of moisture appeared, trapped beneath the skin, on the palm of one hand, and with them came a compelling urge to scratch. Then I started to claw at my left hand with the nails of my right until blood ran. This mania of scratching continued until the whole surface of the hand turned raging, stinging scarlet and there came, despite the wound (or perhaps because of it), a sense of release, followed almost immediately by guilt.

I tried repeatedly to reconcile these warring views until, eventually, it all extruded through my hands, unerring somatic proof (the body being an incorrigible punster) that I couldn’t in fact handle it. Beads of moisture appeared, trapped beneath the skin, on the palm of one hand, and with them came a compelling urge to scratch. Then I started to claw at my left hand with the nails of my right until blood ran. This mania of scratching continued until the whole surface of the hand turned raging, stinging scarlet and there came, despite the wound (or perhaps because of it), a sense of release, followed almost immediately by guilt.

This sequence was repeated many times until the palm was florid with yellow and green crests of pus. The other hand also became infected. They seemed like self-inflicted stigmata, visible and so particularly shaming.

Traumatic legacy

From childhood through youth and into early adulthood, Karpf struggled with the weight of her family’s traumatic legacy. The excessive fear for her family’s safety itself was traumatic. Karpf finds herself caught between two conflicting pressures. On the one hand, there is the expectation to respect her parents’ Holocaust legacy by maintaining what she describes as an ‘undifferentiated’ and ‘unicellular’ relationship with them. This obligation tethered her to their experiences, compelling her to carry the burden of a history that predates her own existence. On the other hand, she self-imposes a mission to redeem her parents’ suffering by achieving personal success and happiness while suppressing her negative emotions. The conflicting currents of duty and personal fulfilment create a profound tension that echoes through Karpf’s formative years.

Karpf yearns to break free from the symbiotic bond with her parents, desiring to forge her own path in life untouched by the family trauma she has not personally experienced. The struggle to claim an independent identity was particularly a challenge for Karpf. Her reflection, “It seemed then as if I hadn’t lived the central experience of my life — at its heart, at mine, was an absence,” condenses the impact of an event that casts a long shadow over her existence. The writers of the Holocaust second generation carry a legacy that sets them apart from their contemporaries—a mark not etched by their own experiences but one inherited from a history they never lived. In the words of Nadine Fresco, this manifests as a visceral feeling akin to the body displaying symptoms of a trauma it never directly experienced.

Karpf yearns to break free from the symbiotic bond with her parents, desiring to forge her own path in life untouched by the family trauma she has not personally experienced. The struggle to claim an independent identity was particularly a challenge for Karpf. Her reflection, “It seemed then as if I hadn’t lived the central experience of my life — at its heart, at mine, was an absence,” condenses the impact of an event that casts a long shadow over her existence. The writers of the Holocaust second generation carry a legacy that sets them apart from their contemporaries—a mark not etched by their own experiences but one inherited from a history they never lived. In the words of Nadine Fresco, this manifests as a visceral feeling akin to the body displaying symptoms of a trauma it never directly experienced.

Fresco compares the second generation to amputees left with phantom pains. Much like the lingering sensations in a non-existent hand, these individuals are compelled to struggle with the intangible yet intense effects of a history that precedes their own existence. The pain may be phantom, but its impact is intensively real. This is a unique kind of suffering.

Phantom pain

For these latter-day Jews, the analogy of a phantom pain wraps up the paradoxical nature of their connection to an unlived past—a past that shapes their identity, influences their relationships, and permeates their understanding of the world. The phantom pain becomes a symbolic thread that waves their narratives, a constant reminder of a history that never ceases to influence. The writers of the second generation invite us to witness the complexities of their journey— one marked by the simultaneous presence and absence of a history that binds them to the past.

Second-generation writers, such as Karpf, encounter themselves in a crisis of signification—a challenge rooted in their disconnected relationship to the Holocaust, an event they did not directly experience but sense through its haunting absence. These writers employ imaginative writing as a tool to relive the crisis. The core objective is to reconnect with the Holocaust past of their parents. Through the lens of imagination, they strive to establish a link between the event itself and its enduring effects on their lives. The act of imaginative writing becomes a bridge, a means to explore the indescribable and inexplicable. This may seem an obsessive engagement for the rest of the scribe fraternity. However, for second-generation writers, this very act of creative reconstruction becomes a form of remembrance, a way to imagine an event of which they cannot be epistemologically certain. The writers, in their pursuit, aim not only to tell the story but also to continue restoring some of the holes in the collective memory of the Holocaust.

Marianne Hirsch’s concept of postmemory holds particular relevance in understanding the second generation’s response to the trauma of the first. This concept sums up the epistemological and experiential distance from traumatic events. In their imaginative writing, the second-generation deals with the complexities of postmemory. Their ultimate objective is well beyond bridging the gap between generations.

They are compelled with a conscious obligation to ensure that the legacy of the Holocaust is not forgotten.