The age of modern empires started with the advanced technological upheavals in the West that elevated the first European powers such as Portugal and Spain to subdue the African and Asian cultures.

But, the West’s encounter with the South Asian nations met with a vehement resistance arose from the native communities who showed an indomitable spirit. The case of Sri Lanka provided a remarkable precedent for all the colonised nations in the 16th and 17th centuries as the Sinhalese forces fought tooth and nail against the Western conquerors regardless of their technological superiority.

Dambadeni Asna

Sinhalese forces were not accustomed to the fire-armed technology until the arrival of the Portuguese in 1505. Portuguese historian Queyroz provides a detailed account of the frightened reaction of the masses in Colombo before the sounds of Portuguese cannon balls. Although Western sources attribute the Portuguese as pioneers who brought firearms to Sri Lanka, gunpowder was used in Sri Lanka at least by the 14th century. The famous “Dambadeni Asna”, an old leaf manuscript belonging to the Dambadeniya era in the 14th century provides clues on the usage of gunpowder by the Sinhalese forces in the medieval period.

Some of the gunshots mentioned include Wala wedi, Mahawedi, Dum wedi, Yathuruwedi, Gal wedi, Gini wedi and Weliwedi. The usage of gunpowder technology existed, albeit with a rather minimal effect until the arrival of the Westerners. The local sources remain silent on the inception of the gunpowder technology in medieval Sri Lanka as none of the sources either explicitly or implicitly refereed to the places from where Sinhalese borrowed the technology. Even though it is a question that goes beyond the ken of a trained historian, the development of gunpowder technology in Dambedinya alludes to the Arabic influence as there was a considerable Muslim population in Sri Lanka by the 14th century.

Some of the gunshots mentioned include Wala wedi, Mahawedi, Dum wedi, Yathuruwedi, Gal wedi, Gini wedi and Weliwedi. The usage of gunpowder technology existed, albeit with a rather minimal effect until the arrival of the Westerners. The local sources remain silent on the inception of the gunpowder technology in medieval Sri Lanka as none of the sources either explicitly or implicitly refereed to the places from where Sinhalese borrowed the technology. Even though it is a question that goes beyond the ken of a trained historian, the development of gunpowder technology in Dambedinya alludes to the Arabic influence as there was a considerable Muslim population in Sri Lanka by the 14th century.

Muslims knew the use of famous Greek Fire, which was used by the Byzantium rulers to chase Arabic invaders from capturing Constantinople and it is plausible to assume that Muslim traders, who came to Sri Lanka in the late medieval era initiated the gunpowder technology in Sri Lanka. Before the advent of Europeans, the weaponry that existed in Sri Lanka may have had some trace of gunpowder technology due to the presence of the Arabic traders in Colombo and it may be a naïve assumption to suggest that the influx of Europeans in the 16th century astounded the locals.

The technological advancement of the Portuguese hampered the indigenous resistance that arose from the locals in the maritime provinces against the hostilities of the Portuguese soldiers. Mayadunne, the ruler of Sitawaka was the first native king to realise the imperative of developing firearm technology to confront the superiority of the European powers. He was assiduous in making a strategic alliance with Zamorin, the Muslim ruler in Calicut to subdue the growing Portuguese influence in the region and these efforts got nipped in the bud as the Portuguese followed a formidable defensive approach in Colombo, which resulted in the complete annihilation of the firearms sent by Zamorin.

Mayadunne’s son, Rajasinghe went a few steps further as he openly patronised local craftsmanship of firearms. The Arab artisans, Portuguese renegades were encouraged to settle in the provinces of Sitawaka to bolster the process of manufacturing the firearms such as guns, muskets and canons. He sought assistance from Calicat and the rising commercial power in Sumatra to construct a strong navy. Tremendous amount of work and enthusiasm of Rajasinghe reached its nadir with his untimely demise, which finally pushed the kingdom of Sitawaka into the control of Portuguese.

Mahatuwakku and Kara Thuwakku

The next crucial stage of the development of the firearms in Sinhalese army was visible in the Kandyan kingdom, wherein Sinhalese sovereignty was at bay before the steep increase of Western powers. There were different types of firearms deployed by the Sinhalese army blended between the technology borrowed from the Europeans and native craftsmanship.

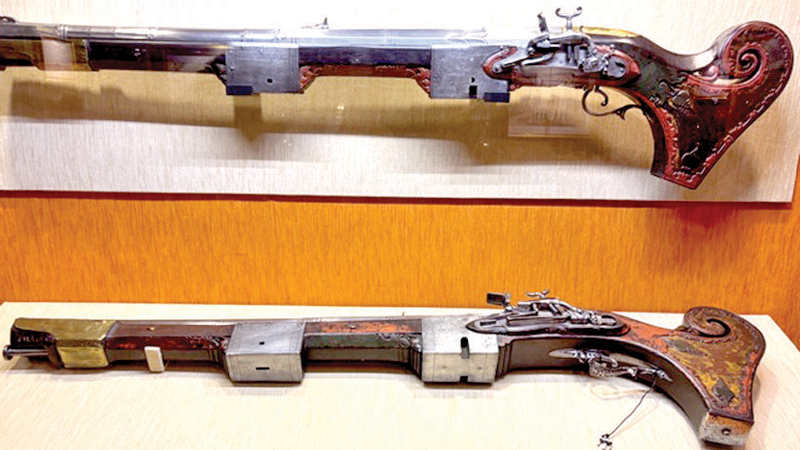

The collection of artefacts returned by the Dutch to the Sri Lankan museum recently is an embodiment for the firearm technology of the Sinhalese in the 17th and 18th centuries as the collection consists of two guns used by the Kandyan army known as Mahatuwakku.

The gun called Mahatuwakkuwa is a scaled-up version of a standard infantry gun. It is also called “Kara Thuwakkuwa” as it is heavy and required to be carried on the shoulder. This gun consists of smoothbore gun barrels which have an inside diameter of 1.37 inches and 1.25 inches, mounted onto the stock by pins.

The firing mechanism is identified as a flintlock firing mechanism and referred to as “Bodikula” in Sinhala. The vertical grooves of the frizzen increases the friction between the fizzen and the flint, which creates enough sparks to fire gun and also help to drain off any water or dew off the frizzen thereby avoiding misfires. Both of this gun consists of “Cross-Slot Screws”. These Cross-slot screws have been used in points where high torque is used, such as to secure the lock plates to the stock. The remarkable feature of this gun called “Mahatuwakkuwa” is the detachable pan, which helps to increase the rate of fire of the guns.

In an article authored by P.D.P Deraniyagala to the Journal of Royal Asiatic Society in Ceylon, the author states some of the Sinhala flintlock guns are the most artistic and ornate guns known [..] and well merit the encomiums of the medieval Europeans. The entire weapon, both metal and wood, is often profusely ornamented, the stock being fretted with delicate traditional designs and inlaid with carved ivory or tortoise-shell panels, while the barrels are inlaid with silver or gold.

Deraniyagala’s description is a stark example of the Sinhalese craftsmanship in manufacturing firearms. Thus, it is worthy to note that the firearms and gunpowder technology was not a random science introduced to Sri Lanka by the Westerners as its roots have been imbued with indigenous technology.

The writer is the Joint Secretary at the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka.