This year’s World Day Against Child Labour, to be marked on June 12, will focus on celebrating the 25th anniversary of the adoption of the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (1999, No. 182) under the theme “Let’s act on our commitments to End Child Labour”.

This year’s World Day Against Child Labour, to be marked on June 12, will focus on celebrating the 25th anniversary of the adoption of the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (1999, No. 182) under the theme “Let’s act on our commitments to End Child Labour”.

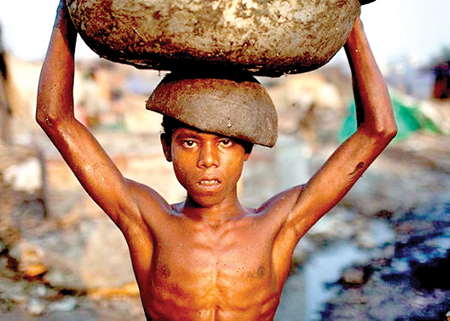

Although significant strides have been taken in reducing child labour over time, recent years have seen global trends reverse, underscoring the pressing need to unite efforts in expediting actions to eradicate child labour in all its manifestations.

With the adoption of Sustainable Development Goal Target 8.7, the international community made a commitment to the elimination of child labour in all its forms by 2025. But this is unlikely to happen, with the deadline less than six months away.

This World Day Against Child Labour, the United Nations (UN) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) are calling for: The effective implementation of the ILO Convention No. 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labour; Reinvigorated national, regional and international action to end child labour in all of its forms, including worst forms, through adopting national policies and addressing root causes as called upon in the 2022 Durban Call to Action; Universal ratification and effective implementation of ILO Convention No. 138 on the Minimum Age, which, together with the universal ratification of ILO Convention No. 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labour achieved in 2020, would provide all children with legal protection against all forms of child labour.

Achievements

Since 2000, for nearly two decades, the world had been making steady progress in reducing child labour. But over the past few years, conflicts, crises and the Covid-19 pandemic, have plunged more families into poverty – and forced millions more children into child labour. Economic growth has not been sufficient, nor inclusive enough, to relieve the pressure that too many families and communities feel and

that makes them resort to child labour. Today, 160 million children are still engaged in child labour. That is almost one in ten children worldwide.

that makes them resort to child labour. Today, 160 million children are still engaged in child labour. That is almost one in ten children worldwide.

Africa ranks highest among regions both in the percentage of children in child labour — one-fifth — and the absolute number of children in child labour — 72 million. Asia and the Pacific ranks second highest in both these measures — 7 percent of all children and 62 million in absolute terms are in child labour in this region.

The Africa and the Asia and the Pacific regions together account for almost nine out of every ten children in child labour worldwide. The remaining child labour population is divided among the Americas (11 million), Europe and Central Asia (6 million), and the Arab States (1 million). In terms of incidence, 5 percent of children are in child labour in the Americas, 4 percent in Europe and Central Asia, and 3 percent in the Arab States.

While the percentage of children in child labour is highest in low-income countries, their numbers are actually greater in middle-income countries. Nine percent of all children in lower-middle-income countries, and 7 percent of all children in upper-middle-income countries, are in child labour.

Education is a basic right of every child, but worldwide there are around 300 million children and youth around who do not go to school. They do not get to put on a uniform and walk or take a bus to school; they do not get to sit in a classroom, listen to a teacher, read a textbook and take notes. They do not have the opportunity to learn to read, write and do math.

Local situation

The situation in Sri Lanka is very different, as there is near-universal school attendance by both boys and girls (in many countries, girls are compelled to stay at home doing housework, which is an unpaid form of child labour). There is a good chance that many of these children who cannot attend school for whatever reason end up doing menial jobs to support their parents. Too many children around the world don’t even have a chance to be children. Worldwide, it is estimated that more than 160 million children are engaged in child labour, half of whom are in hazardous work; 112 million are in agriculture. The recruitment of child soldiers continues.

Most often because their families live in poverty, children are asked to contribute to their livelihoods or to “earn their keep”. They do household chores like cleaning, cooking and fetching water, selling goods or working in factories. Child labour can be a couple of hours a day to a full day. The children are paid very little, if at all.

Child soldiers are deployed in many conflicts around the world, which means they have no chance at all for any kind of education, apart from weapons training. This is another very harsh form of child labour, if the term can be applied to this situation. It is a gruelling life as many of them are abducted in the first place and then compelled to undergo training, with rudimentary facilities and meagre food rations. In Sri Lanka, the LTTE had such “baby brigades” and rebel groups in many countries deploy child soldiers.

Thousands of children are also trafficked for sex and slavery worldwide. Slavery is the worst form of child labour. Conflicts and terrorist incidents have displaced children and separated them from their parents, as have natural disasters. More than 50 million children have been uprooted from their homes due to conflict, poverty and climate change while millions more face violence in their communities.

Uncomfortable truth

The world has to confront the “uncomfortable truth” that around the planet, the rights of millions of children are being violated every day. But this is an issue that calls for global action as child labour and similar phenomena are found worldwide.

The ILO launched the first World Day Against Child Labour in 2002 as a way to highlight the plight of children engaged in child labour. The abolition of child labour is a cornerstone of the aspiration for social justice, through which every worker can claim freely and on the basis of equality of opportunity and treatment their fair share of the wealth that they have helped to generate.

The United Nations (UN) and experts tackling Child labour over the course of the past three decades has demonstrated that child labour can be eliminated, if the root causes are addressed.

The United Nations (UN) and experts tackling Child labour over the course of the past three decades has demonstrated that child labour can be eliminated, if the root causes are addressed.

Granted, some categories of child labour are somewhat hard to define. If a child works after school in a shop owned by the parents, is it child labour or just helping the parents out? If a child helps his parets in a farm, can it be classified as child labour? Such unseen (and unpaid) child labour is also major issue.

Sri Lanka has taken stringent measures to curb child labour but the last ILO survey in 2016 revealed that around 43,000 children here are engaged in labour, mostly in rural areas as contributing family members. For example, many children work in the farms owned or leased by their parents.

Though these numbers may have come down in the intervening years, there still are pockets of child labour in agriculture, construction and industry. However, unlike in many other countries in our region, the majority of them are boys. Again, the biggest consequence is that many of them attend school irregularly and some drop out altogether by Year 8 or 9. They do not pick up any other skills too in the meantime and are destined to a life of menial labour, unless they are directed for vocational training etc.

Thus child labour is a blight on our future and should be eliminated as soon as possible. Nevertheless, 2025 is too ambitious a target to end child labour – 2030 or 2035 looks like a more realistic target. But Governments and other stakeholders must begin work on it right away so that it will be possible to eliminate this scourge from our midst at least within the next decade or so.

****

What is Child Labour

Not all work done by children should be classified as child labour that is to be targeted for elimination. The participation of children or adolescents above the minimum age for admission to employment in work that does not affect their health and personal development or interfere with their schooling, is generally regarded as being something positive.

This includes activities such as assisting in a family business or earning pocket money outside school hours and during school holidays. These kinds of activities contribute to children’s development and to the welfare of their families; they provide them with skills and experience, and help to prepare them to be productive members of society during their adult life.

The term child labour is often defined as work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development.

It refers to work that:

• is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children; and/or

• interferes with their schooling by: depriving them of the opportunity to attend school; obliging them to leave school prematurely; or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work.

Whether or not particular forms of work can be called child labour depends on the child’s age, the type and hours of work performed, the conditions under which it is performed and the objectives pursued by individual countries. The answer varies from country to country, as well as among sectors within countries.

The worst forms of child labour

The worst forms of child labour involve children being enslaved, separated from their families, exposed to serious hazards and illnesses and/or left to fend for themselves on the streets of large cities – often at a very early age.

Whilst child labour takes many different forms, a priority is to eliminate without delay the worst forms of child labour as defined by Article 3 of ILO Convention No. 182:

(a) all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery, such as the sale and trafficking of children, debt bondage and serfdom and forced or compulsory labour, including forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict;

(b) the use, procuring or offering of a child for prostitution, for the production of pornography or for pornographic performances;

(c) the use, procuring or offering of a child for illicit activities, in particular for the production and trafficking of drugs as defined in the relevant international treaties;

(d) work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children (hazardous child labour or hazardous work).

-ILO