- Transport, Highways and Mass Media Minister Dr. Bandula Gunawardena

Minister of Transport, Highways, and Mass Media, Dr. Bandula Gunawardena, talking to the Sunday Observer highlighted that President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s Leadership in economic recovery is vital and twice in history he stepped forward to save the country.

Moreover, Dr. Gunawardena said that irrespective of whether it is UNP, SLPP, JVP, SJB or any other party that comes into power, they will have to adhere to the agreements with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), if not the country will struggle even to endure two weeks.

Dr. Gunawardena highlighted that altering IMF agreements are not a walk in the park because agreements are signed not with political parties but with nations. Thus, any attempt to amend these conditions would result in inevitable fiscal collapse.

The following article is based on an interview with Minister Gunawardena. His views and perspectives are reflected in this article.

****

For the first time in the history of Sri Lanka after independence, in 2001, the economy regressed, leading to an economic collapse that could not withstand external shocks from the global market. During that time, due to the military situation in Sri Lanka and the inability to prepare for international shocks, the demand for exports decreased.

Local market goods were in short supply. Inflation rose sharply. exchange reserves collapsed. The rupee depreciated. Electricity was frequently cut off. The budget gap widened. Debt crises intensified. As the economic crisis worsened, President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s Government was unable to manage the country effectively. Consequently, a part of that Government broke away, and United National Party (UNP) leader Ranil Wickremesinghe became the Prime Minister and appointed a new Cabinet.

Local market goods were in short supply. Inflation rose sharply. exchange reserves collapsed. The rupee depreciated. Electricity was frequently cut off. The budget gap widened. Debt crises intensified. As the economic crisis worsened, President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s Government was unable to manage the country effectively. Consequently, a part of that Government broke away, and United National Party (UNP) leader Ranil Wickremesinghe became the Prime Minister and appointed a new Cabinet.

Despite the economic collapse, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe stepped forward to save the country. He secured an agreement with the IMF and rebuilt the collapsed economy within a year. What happened once in history happened again.

To rebuild the collapsed country and prevent future bankruptcy, Premier Wickremesinghe introduced the Fiscal Management (Responsibility) Act (No. 3 of 2003). Wickremesinghe remains the only politician in Sri Lankan history to pass the Fiscal Management (Responsibility) Bill in Parliament, imposing necessary conditions to legally prevent the country from going bankrupt.

Therefore, with his experience in recovering the country, President Wickremesinghe stands out as a political leader with mature political leadership and economic vision, capable of securing the necessary international support with experience and patience.

Therefore, with his experience in recovering the country, President Wickremesinghe stands out as a political leader with mature political leadership and economic vision, capable of securing the necessary international support with experience and patience.

Restructuring foreign debt is imperative. It is a truth we must logically accept: without restructuring, no Government can maintain stability for even two weeks. This is evident in Sri Lanka’s economic collapse in 2022, one of the worst in recent history. We must admit that, under these circumstances, governing the country is unfeasible. The bankruptcy is not the fault of any single person or Government. The continuous deficit in the current account of the State Budget for three decades is to blame. Because of this, no Government has received enough income to even cover daily expenses.

This situation that was same in the past, remains so now, and will likely persist in the future. Government employee salaries, pensions, social beneficiary schemes like Samurdhi and Aswesuma, and the long-standing crisis of insufficient income to cover foreign debt are all part of the problem. Some attribute this crisis to the reduction of VAT by former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, but this claim lacks scientific basis. The truth is that there has not been enough income to cover expenses for a long time.

In 2023, the Treasury received only Rs. three trillion in tax and non-tax income, including grants. However, necessary expenditures amounted to Rs.4.6 trillion. Thus, in 2023, there was a deficit of Rs.1.6 trillion. It is clear that this shortfall must be addressed, regardless of which party governs or who comes to power. Money is needed to cover essential expenses.

Previous Governments used to borrow to cover the current account deficit both domestically and internationally. When these loans proved insufficient, Supplementary Estimates were issued, and money was minted. Currently, both of these options are impossible. Due to our failure to repay foreign loans, we are unable to secure further credit, and printing money is also prohibited. These facts are key reasons for the worsening crisis. There has always been a current account deficit under any Government.

Historically, salaries and other expenditures were covered locally by borrowing amounts equivalent to the current shortfall of Rs.1.6 trillion. Since Independence, no Government has had enough revenue to sustain itself, and all development work was financed through borrowed money, not through public taxes. Loans from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) were used to build infrastructure such as roads.

This financial approach highlights the chronic issue of insufficient revenue and underscores the urgent need for restructuring foreign debt to stabilise the economy and ensure sustainable governance.

The second factor contributing to the country’s bankruptcy is the deficit in the current account of the balance of payments. This means that the amount of foreign exchange leaving the country for transactions each year exceeds the amount coming in from external trade.

Since 1977, the balance of payments has consistently shown a negative value. Sri Lanka has always struggled to earn enough foreign exchange to import essential goods like mineral oil, gas, rice, flour, and machinery. These necessities have always been imported on credit.

To cover the current account deficit in the balance of payments, the country has relied on foreign loans. This persistent reliance on external debt to bridge the gap in the balance of payments has been a significant factor in worsening the economic crisis.

Due to the significant increase in the current account deficit in the balance of payments, foreign borrowing has led to the continued depreciation of the Rupee. The Rupee has collapsed over the years. In 1977, eight rupees were paid per dollar. After the November Budget of that year, the exchange rate was adjusted to 16 rupees per dollar. Under the Mahinda Rajapaksa Government, the rate was 105 Rupees per dollar, and by the end of that Government, it had reached 131 Rupees per dollar. During Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s tenure, the rate was 200 Rupees per dollar. Amid the economic crisis, the rate in the black market soared to 420 Rupees per dollar. Today, the official rate stands at around 300 Rupees per dollar.

The sharp depreciation means that where we once paid just 8 Rupees for a dollar’s worth of goods, we now pay 300 Rupees or more. This dramatic increase in the Cost of Living (COL) is something our people must understand, as it directly impacts the prices of goods and services. The persistent deficits in the current account of the state budget and the current account of the balance of payments have been financed through both domestic and foreign borrowing.

It is crucial to acknowledge these economic realities to comprehend why reducing the prices of goods is not as simple as it might appear. The structural issues in our economy must be addressed to create sustainable solutions.

We knew that we would go into bankruptcy based on our situation; therefore, we signed 16 agreements with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Time and again, recommendations were made to save the country from bankruptcy. However, these recommendations were opposed, and the agreements were broken.

Before this recent collapse, the first significant economic crisis occurred in 2001, during the presidency of Chandrika Kumaratunga. At that time, Dr. P. B. Jayasundara, who was the Secretary of the Ministry of Finance, witnessed the economy contract by 1.4 percent, marking the first crash. The country’s economic crisis escalated, leading to the formation of a new Government under the leadership of Ranil Wickremesinghe. In that Government, I served as the Cabinet Minister for Rural Affairs and Deputy Minister of Finance.

The IMF, based on our contractual relationship, advised us that the country could not continue on its current path. Consequently, a law was passed in Parliament to prevent such situations from occurring again. Understanding the history of these economic agreements and crises is crucial for addressing the structural issues that have led us to our current state. We must learn from past mistakes and ensure sustainable governance and economic policies moving forward.

Accordingly, in 2003, the Financial Management Responsibilities Act, also known as the Fiscal Management Responsibility Bill, was introduced, and three key provisions were enacted.

Firstly, in 2006, it was mandated that the budget deficit must not exceed 5 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This measure aimed to maintain fiscal discipline regardless of which party was in Government.

Secondly, by 2013, it was stipulated that the total outstanding public debt should not exceed 65 percent of the GDP. This measure was implemented to prevent a debt payment crisis.

Thirdly, the Government was limited to guaranteeing loans up to 4.5 percent of the GDP. These laws were introduced during the leadership of the then Premier Ranil Wickremesinghe, who spearheaded the recovery of the country from a collapsed state. These measures were enacted to safeguard the country from bankruptcy.

However, these reforms came at a cost, and significant sacrifices were made. Public sector recruitment was halted through a circular, and the negative economy was bolstered through painstaking efforts. The recovery process in 2001 similarly involved painful experiences for the common people.

Based on these developments, there is a prevailing sentiment that the country was betrayed in 2004 when we were sent home. P. B. Jayasundara, the Secretary of the Ministry of Finance under the incoming Government at the time, amended the Financial Management Responsibilities Act. This amendment effectively altered the provisions of Act No. 3 of 2003.

All parliamentary representatives involved in amending the existing financial management laws in 2004 should bear the responsibility for the country’s descent towards bankruptcy. The amendments made during that time have had profound implications for the nation’s fiscal health and stability.

Subsequently, successive Governments continued the practice of servicing the national debt through conventional means. In cases where subsidized loans from institutions like the World Bank and the IMF proved inadequate, Governments resorted to seeking additional funds from the international market by issuing sovereign bonds, albeit at significantly high interest rates.

During the tenure of President Mahinda Rajapaksa, sovereign bonds were issued to finance wartime expenditures, resulting in the acquisition of billions of US dollars, totaling approximately US$ 6.5 billion.

However, under the Good Governance Government in 2015, a notable increase was observed in International Sovereign Bond (ISB) issuances. The administration procured ISBs worth approximately US$ 12 billion in just for five years, indicating a significant uptick in borrowing from international markets.

Fitch Rating, a globally recognised institute for international credit assessment, along with other esteemed institutions such as Moody’s, has downgraded Sri Lanka due to concerns surrounding its lack of debt sustainability. Subsequently, there have been claims from local voices suggesting that misinterpretation of Sri Lanka’s economic program led to this decline in rankings. However, it is important to note that entities analysing the global financial landscape possess a comprehensive understanding of our nation’s economic data, making them authoritative bodies in this domain.

While the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) and politicians may assert our solvency and ability to meet debt obligations, the repercussions of a downgrade are undeniable. One significant ramification is the hindrance in issuing Letters of Credit (LCs). In such a scenario, Sri Lankan banks must secure guarantees from third-party entities – for example, requiring an American bank to provide assurance when issuing LCs. This added step inevitably results in additional expenses incurred throughout the process.

As a consequence, our foreign reserves were depleted to zero. This resulted in a severe shortage of funds to pay for essential imports, such as oil tankers and gas shipments. Consequently, there was a breakdown in various essential services, including the electricity supply. Exploiting the situation, certain extremist elements misled the public, accusing the Government of misappropriating funds. Tragically, a Member of Parliament (MP) was killed, and violent unrest erupted, with numerous incidents of destruction.

Amidst this chaos, there emerged a dire need for competent leadership to navigate the crisis. Ranil Wickremesinghe, with his proven track record of steering the country out of crises, like in 2002 , stepped forward. He pledged to engage with the international community and secure assistance to stabilise the country’s precarious situation. Consequently, he initiated negotiations with the IMF and successfully established an Extended Fund Facility (EFF). This agreement with the IMF carried stringent terms and conditions that were binding, regardless of which party was in power.

Once these agreements were entered into, they were considered inviolable, underscoring the imperative for adherence, irrespective of personal preferences or political affiliations. Therefore no matter who comes into power the agreements with the IMF have to be continued because we cannot violate those agreements like we did in the past 16 times.

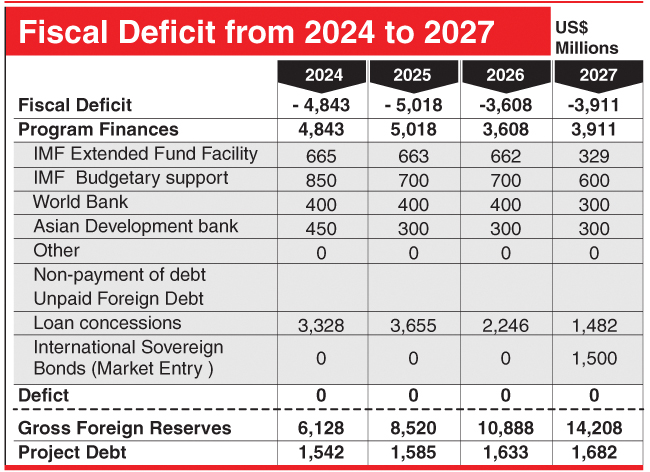

The Presidential Election (PE) is scheduled to take place at the end of this year, with 2025 being just six months away. Based on the provided information, it is anticipated that more than US$ 5 billion will be insufficient to address international financial obligations after 2025.

To address this impending shortfall, a loan agreement has been formulated to secure funds. Under this EFF, the IMF will provide US$ 663 million, with an additional US$ 700 million earmarked for the incoming Government’s budget in 2025. Additionally, the World Bank will contribute US$ 400 million, while the ADB will provide another US$ 300 million.

This loan agreement delineates how the funds will be allocated to mitigate the anticipated financial gap in 2025.

When a new Government assumes power, its first task is to address how it will formulate the budget given potential changes to existing agreements within six months. This is crucial for planning and executing development projects in the country. Even by 2027, there will still be a shortfall of US$ 3,911 million for major international transactions.

To bridge this gap, the IMF will provide US$ 329 million through EFFs, with an additional US$ 600 million allocated for expenses. The World Bank and the ADB will each contribute US$ 300 million, along with a loan relief of US$ 1,482 million.

Despite these measures, there will still be a shortfall of US$ 1.5 billion by 2027. At that point, the country will be permitted to seek funds from the international market. However, until then, regardless of the governing party, access to international markets will be restricted. Whether it is JVP or any other political party until 2027, we cannot reach the international market. Even then, we can only get US$ 1.5 billion.

Analysing this reality, it appears that whoever comes to power can govern with relative freedom. International resources must increase to US$ 14 billion at the time of ISB issuance to borrow US$ 1.5 billion. The government of Sri Lanka has been allowed to pay bilateral and commercial debts up to 2027. An agreement should be reached on how to manage debt payments beyond 2027. To achieve this, all political parties must agree on the terms and numbers, enacting them into law through Parliament.

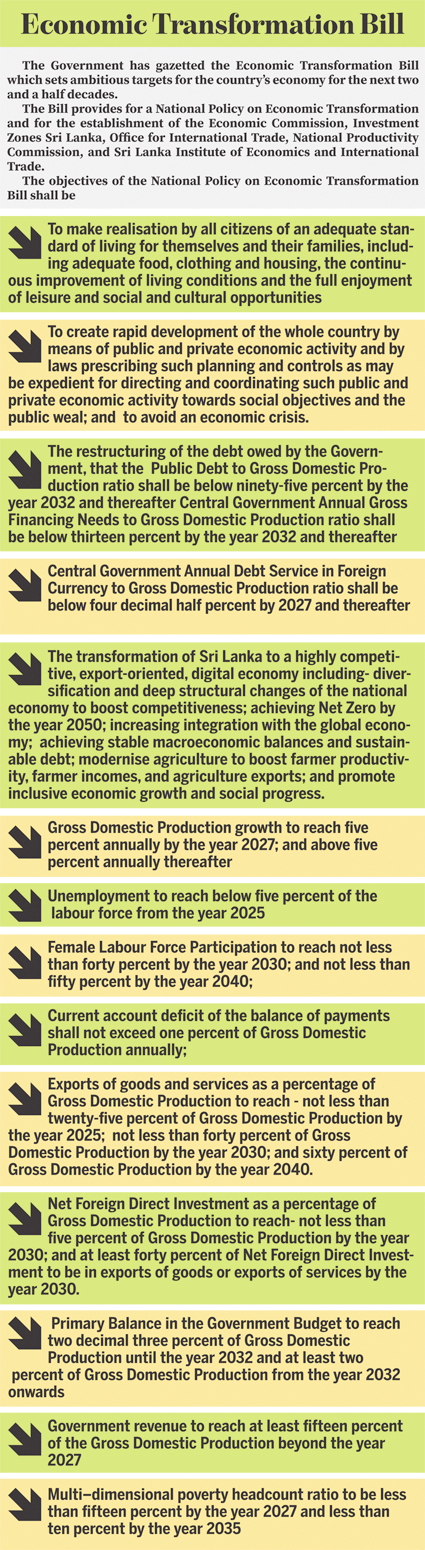

Accordingly, the Economic Transformation Bill (ETB) has been submitted to Parliament.

To restructure public debt by 2032, Sri Lanka must communicate its commitment to reducing outstanding debt to 95 percent of GDP. It is imperative that the Gross Fiscal Requirement per year of GDP remains capped at 13 percent under any Government. Loan tenure and interest payments from GDP cannot exceed 4.5 percent. The country must maintain an economic growth rate of 5 percent or more. The current account deficit in the balance of payments by GDP should not exceed 1 percent, and the proportion of unemployed individuals should decrease to 5 percent. It is upon these terms that foreign debt restructuring can be pursued.

The loan repayment agreement will be established post-2027. Approximately 37 percent of outstanding loans are projected to be repaid within the first 5-6 years, while 51 percent of foreign debt falls due between 6-20 years. The remaining 12 percent is anticipated to be settled after 20 years. The aim is to manage this debt restructuring from 2027 to 2048.

These parameters outline the framework within which debt restructuring negotiations are conducted. Without these agreements being enshrined as national commitments, no Government can ensure the provision of essential commodities such as oil, gas, medicine, and electricity to the populace. Failure to adhere to these agreements risks perpetuating a cycle of crisis, unlike in 2022, resulting in long-term adverse consequences and potential disaster.

The former head of the IMF once said that Sri Lanka would inevitably have to tread a paved path in the future. However, the Opposition insists on altering the IMF’s conditions upon assuming power. It is crucial to understand that the IMF engages not with individuals or political parties, but with nations. Agreements are forged with a State, and when individuals depart, they depart along with the country’s obligations. Any attempt to amend these conditions would result in inevitable fiscal collapse. The nation would struggle to endure even two weeks under such circumstances, leading to widespread turmoil that cannot be mitigated.