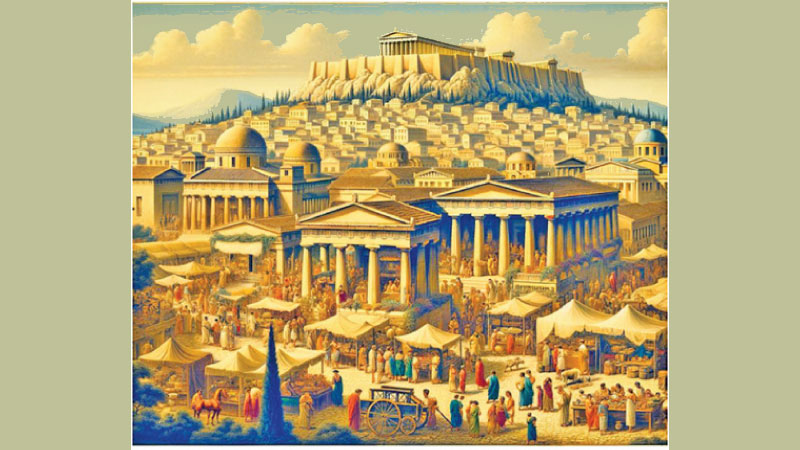

Athenians were proud of their democracy; and historians like Thucydides understood its importance to the State and underscored the necessity of having able leaders such as Pericles to guide the city state in times of war and peace. The democracy as we know of today and what was practised in Athens during her prime was a very different mechanism altogether.

Athenians were proud of their democracy; and historians like Thucydides understood its importance to the State and underscored the necessity of having able leaders such as Pericles to guide the city state in times of war and peace. The democracy as we know of today and what was practised in Athens during her prime was a very different mechanism altogether.

In Athens, the rule of the people was that of a minority who banked on the glory of the Athenian Empire. The citizenship law of Pericles further narrowed down the Athenians with an exclusivity that was not seen anywhere else in Greece. The population of Athens and surrounding Attica during the mid fifth century was around 250,000 to 150,000 people; from this number, only 30,000 were Athenians.

The bust of Kleon

The rest comprised metics (foreigners) and slaves. For Athenians, their citizen democracy was an effective method of creating an ordered and powerful State. Athenian democracy was not wholly for the people, it also served the double purpose of maintaining the Empire.

The Athenian naval empire used their supremacy to rule their subjects and control their imports and exports. In the constitution of Athens, pseudo Xenophon emphasised the importance of being able to import goods unable to be grown in their harsh soil and to export the goods available to them. Since the Athenian fleet controlled most of the Aegean trade routes, it was very easy for them to restrict trade to and from subjects when it benefited the Empire. As pseudo Xenophon says, “If some city is rich in iron, copper or flax where will it distribute without the consent of the rulers of the sea”.

Direct democracy

Ste Croix says Athens’ naval imperialistic policies were not merely the result of “naked aggressiveness and greediness”. The socio-economic system was thus that the Athenian population of citizens, metics and slaves were fed with the largest quantity of imported corn than any other State. In return, Athens sent silver, olives, and painted pottery. Corn and wheat were the staple food for most Greek States.

Some states were self-sufficient in this respect, which was sorely missing in Athens, partly due to her soil which was uncongenial for most large scale crops. Athens’ dependence on foreign corn meant Athens has to secure the trade routes from her enemies. Thus, Athens’ imperial policy saw the preservation of the corn routes which also secured her from starvation.

The development of the naval empire affected the practice of direct democracy at home. The economy of Athens aforementioned was largely based on the imports and exports which brought many goods and luxuries into the city. This aspect came under the care of the metics. It was important to have metics in the State to run the businesses at home. The metics were considered equal to citizens in most areas except for voting rights. Even the slaves had a rather comfortable and decent life and were treated with civility.

Athens and democracy flourished because of the self interests of the people. While the earlier form of democracy benefited the State, the more radical democracy seen after the Periclean age was a double edged sword. A most striking quality of the empire was that equality was confined to Athens.

The naval empire benefitted Athens but was a detriment to her subjects, while the democracy benefited the people of Athens by giving them a share in the political responsibilities of the State. They had the opportunity to partake in the large sums of money the Empire was bringing in to Athens. Pericles states in his funeral oration:

“Our constitution is called a democracy because power is in the hands not of a minority but of the whole people. When it is a question of settling private disputes, everyone is equal before the law; when it is a question of putting one person before another in positions of public responsibility, what counts is not membership in a particular class, but the actual ability which the man possesses. No one, so long as he has it in him to be of service to the state, is kept political obscurity because of poverty”. By increasing the power of the people and allowing more participation in the Government, the Athenians left themselves with no authoritative leader once Pericles died. The policies of democracy sound impressive in theory and practice but they bred certain evils that led to the downfall of Athens.

Since magistrates were chosen by lot and could be elected general multiple times, the office was sought after by ambitious men. The problem with this system was that the military general held supreme authority over military affairs, but did not have any say when it came to political matters. He could, however, influence the Ekklesia to meet his ends and see the policies through.

Pericles was elected general 15 times by the people. The Assembly was by no means composed of intellectuals. Its majority comprised overzealous and fastidious rabble who were swayed under the artful oratory of Pericles. During the incidents that led up to the outbreak of the Peloponnesian war (Which was a result of Athens’ tyrannical bahaviour towards the allies); Periclean oratory incited and swayed the Athenian Assembly towards the war.

The Ekklesia met 40 times a year or more as needed. Never did an Assembly exercise more power or authority than it did in the 5th century Athens. The Assembly heard, decided and received foreign delegations, matters on war and peace, military expeditions, new building programs, dispatched colonies and cleruchies, supervised food distribution and finances.

Age of Pericles

The age of Pericles broke through class barriers like never before. Knowledge of law and politics was diffused throughout the citizen body. An idea on state procedure reached every level of society in Athens. This was unprecedented for any State in Greece.

All distinctions based on wealth faded in practice, and equality had prevailed. Even the poorest could be seen serving as jurors in the public courts, and demagogues from varied backgrounds influenced the assembly with the power of oratory. However, in consequence to these advancements, majority of the populace became mercenary and held an Athenian supremacist ideology thus at times becoming self-serving and irrational.

The fastidious nature of the rabble was also a problem. The Ekklesia which was spurred on towards war was quick to change their minds in due course. After two invasions and a plague, the people wanted no more of it and blamed Pericles as the architect of the war. Ambassadors were sent to Sparta to ask for a truce but nothing was achieved. Pericles rightly believed that Athenian greatness rested on her democratic government and fairness to all. However, he failed to realise that it also rested on the cooperation and dedication to the common freedom of the Hellas which Athens deprived her subject States. This resulted in a dual morality rooted in nationalism that allowed harsh treatment against other States while encouraging solidarity among the Athenian citizens, metics and the slaves.

Since all citizens had a share in the state machinery, no one person enjoyed supreme authority although mass appeal was a possibility. The politics of Athens was largely subjected to the whims and fancies of the masses, if the mob was an unruly one the situation of the State that is ruled by them can only be a disaster.

Pericles was a patriotic man with a national conscience. He knew the acquisition of the Empire was wrong, but they had to protect what was now theirs. He was able to sway the masses at the peak of his power to defend what providence has secured for them and led the Athenians to fight the Peloponnesian War. What Athens needed was more men of his calibre, but the democracy was such that a leader who was able to make judicious decisions on his own had no appeal in the Assembly.

The capricious nature of the mob had to be appeased by a likeminded leader. The Greek city states were fiercely independent and competitive for their own good. Most city states from its inception engaged in hostilities with their neighbours and rivals States. Wars were so common that it formed a part of their reality.

Athens was a prime example. Her growing powers at times made her competitive, ruthless and irrational, and this treatment would not sit well with the allies. The Peloponnesian war saw two Leagues of allies fighting for supremacy over each other, and the growing jealousy and fear of Athenian dominance was a major causative factor for the outbreak of war.

‘‘The real cause of the war I consider to be the one which was formally most kept out of sight. The growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm this inspired in Lacedaemon made war inevitable’’ – Thucydides – History of the Peloponnesian War.

Arrival of Kleon

Following the death of Pericles, demagogues like Kleon steered the war front and represented the working class citizens of Athens, a true man of the people. He was a representation of what democracy stood for, fairness and equity to all. However, he was not portrayed favourably by contemporary writers such as Thucydides and Aristophanes, who accused him of being an unethical war-monger.

He was Pericles’ main opponent whilst alive and questioned his strategies and was in favour of an aggressive approach to the war. Kleon soon became the leading figure of the democratic faction, and he became the first politician to prominently represent the commercial class.

Kleon stayed away from the defensive policies of Pericles, and favoured an offensive tactics against Sparta and her allies. Many ancient critics have commented with derision at his public appeal and for guiding the war as he did. It was the system of the times that allowed men of that composure to guide the fate of Athens.

The aspect of slaves within Athens was also an element which saw to the development of Athenian democracy as well as the iconic image she held in antiquity. Ste Croix believes that without slaves, political democracy would have been unworkable. The vast number of barbarian slaves enabled Athenian citizens to freely participate in the civic and political affairs of the State.

The intellectual revolution and the arts that flourished in Athens was due to the freedom her citizens were privileged to enjoy on the account of slave labour. Whatever the rights and wrongs that may have propelled Athens towards the empire, it was the democracy that prevailed within that enabled Athens to reach such heights of intellectual and political predominance. The empire became synonymous with tyranny, but, on the contrary, advocated a direct democracy at home and among their allies.

The domestic and the external measures which began with the forming of the Delian League was what brought Athens’s motive to the limelight. Athens from the very outset of the Persian wars proved to be brave and selfless ally in the Pan Hellenic League. This enabled Athens to gain the approbation of the allies, and when the Spartans failed to hold on to their favour, Athens was quick to step in and take over the reins of leadership.

The empire and the democracy had a symbiotic relationship. The democratic rule allowed Athenians to choose their leaders and appoint their generals. It is they, most notably, Pericles that steered the fate of Athens thorough the Golden age and the first part of the Peloponnesian war. Every proposal had to be brought before the Assembly and had to be ratified by the people, who were easily swayed by rhetoric and promises of monetary benefits. The large number of slaves and metics that poured into the state allowed the Athenian citizens to partake in state affairs and politics and freed them up from menial labour.

The fruit of the golden age of Athens was due to the freedom and the exclusivity afforded to the Athenians by the empire and democracy. Athens, the democratic empire was a phenomenon that was circumstantial in its evolution, but had far reaching consequences to Athens and the rest of the Greek city states. Concluded.