- “Subjectivity drives true literary criticism”

- A journey through writing, critique and teaching excellence

Emeritus Professor D. C. R. A. Goonetilleke’s contributions to English Literature education and literary criticism in Sri Lanka have been outstanding. His career, which spans over several decades, has shaped countless minds, many of whom are now influential voices in the literary world. Beyond the walls of the university, his presence is felt throughout the academic community. His books, written with clarity and depth, remain indispensable resources for students and researchers alike.

In an interview with the Sunday Observer the Former Head of the Department of English at the University of Kelaniya said he was inspired to pursue a career in literary criticism, firstly, because of his love for books which began in his school days and second, because it suited his temperament.

Aspiring writers and literary critics must try to be up to date by regularly reading the Times Literary Supplement and the New York Review of Books, he said.

A Ph.D. is not the summit of one’s career, but the beginning of one’s future work. “It is important to choose a subject for doctoral research which will act as a springboard,” he said.

Excerpts.

Q: What inspired you to pursue a career in literary criticism and writing?

A: What inspired me to pursue a career in literary criticism was, firstly, that I fell in love with books from my school days, and, secondly, that it suited my temperament.

Q: Could you tell us about your school days and your early career as an English lecturer?

A: The colonial system of education continued in Sri Lanka in the decade after Independence (1948), I was in one of the last such batches, English was virtually the mother tongue; the vernacular, Sinhala or Tamil, was used to speak to underlings though they, too, frequently understood English while they could not speak it. ‘The Secret Sharer’ was one of the British masterpieces of short fiction in an anthology prescribed for the University Entrance Examination in 1956, expecting Sri Lankan students to reach British standards.

My enthusiasm for Conrad, already kindled by reading a volume, Youth, End of the Tether, Heart of Darkness (prescribed for the English Literature syllabus for the G.C.E. Ordinary Level), survived despite ‘The Secret Sharer’ being difficult (though rewarding).

My enthusiasm for Conrad, already kindled by reading a volume, Youth, End of the Tether, Heart of Darkness (prescribed for the English Literature syllabus for the G.C.E. Ordinary Level), survived despite ‘The Secret Sharer’ being difficult (though rewarding).

My school education was at Royal College, Colombo, then the premier (Government) school in the whole island. The teaching of English was conducted with the carrot and stick approach. When Ediriwira Sarachchandra (1914-96) was a boy, a child could be fined five cents for speaking a word of Sinhala or Tamil in school.

Five cents was a significant sum in those days! When he was employed in the early 1940s as a Sinhala teacher at St Thomas’s College, the young Westernised students nicknamed him ‘Tagore’ because they found him amusing. At Royal College, founded by the British in 1835, the top prizes were the Governor-General’s Prize for Western Classics, the Stubbs’ Prize for Latin Prose (Stubbs was a British Governor), the Shakespeare Prize, and the Prize for English Essay. I won the first two which indicated that I possessed a good background for future studies in English.

When I entered the University of Ceylon, our single university at that time, in 1957, F.R. Leavis’ The Great Tradition (1948) was exerting its influence over the Department of English. Leavis placed Heart of Darkness and Lord Jim among Conrad’s minor works, but rated highly Nostromo, The Secret Agent,Under Western Eyes, and Victory.

The lecturers followed Leavis and taught the novels, but not Heart of Darkness. Lord Jim was a favourite of the Professor, Dr. H.A. Passé, who would pose to his students the crucial question, ‘why did Jim jump?’ while performing a little jump himself on the podium! Nostromo was challenging, but we were helped by the similarities between Costaguana and Sri Lanka then – from the bullock-carts to the fluid national set-up, politically semi-patriotic, infiltrated economically and culturally by imperial interests.

The position of Conrad studies in the curriculum received an added interest when Carol Reed’s 1952 film version of An Outcast of the Islands was shot on location in Ceylon. It had a distinguished cast, including Trevor Howard as Willems and Ralph Richardson as Captain Lingard.

Sri Lankans were diverted by Kerima (a stage name meaning ‘Honour’ in Arabic) as Aissa. For publicity reasons, she was projected as having exotic origins, including claims that she was Javanese or Algerian, in keeping with the conception of her as an exotic island girl who embodied the soul of tribal culture amidst the forests. She was regarded seductive, radiant, did not speak, and looked exotic, but she was French! However, no ‘exoticising’ of Kerima caught the interest of the locals.

They were intensely amused at very public amorous attention paid by a woman (Kerima) to a nonplussed professional Kandyan dancer who normally functioned as one of a platoon of men in traditional religious festivals together with magnificently caparisoned tuskers as in D.H. Lawrence’s only poem about Ceylon, ‘Elephant’ (April 1923), irreverently presenting a scion of British royalty being honoured in the colony. As for Kerima, the locals found her uncouth and comic and laughed at her ridiculous behaviour.

When I had performed well at the Final Examination at the University, I was appointed as a Temporary Assistant Lecturer at Peradeniya, but there were no vacancies. I knew that, temperamentally, an academic job suited me best. I joined the permanent staff of Vidyodaya University (The University of Sri Jayewardenepura.) In 1973, I was compulsorily transferred to the University of Kelaniya. I performed well as Professor of English, achieving an international standing as a scholar.

Q: Could you tell us about the books you’ve written and what impact you think they’ve had on literary criticism?

A: I have, so far, written or edited 24 books.

The foundation of my achievements was the Commonwealth Scholarship in the UK in 1966. I was placed at the University of Lancaster. The book version of my Ph.D. thesis was published as Developing Countries in British Fiction by Macmillan in London and Rowman & Littlefield in New Jersey in 1977.

The major writers in the inquiry were Joseph Conrad, Rudyard Kipling, E.M. Forster, Joyce Cary, and D.H. Lawrence. “For the first time, a critic from a developing country studies extensively the British reactions to such countries in the context of the historical, political and personal circumstances from which these reactions emerged” [from the jacket text] – a study acknowledged by international academia as a pioneering step in postcolonial studies. Since then, my major interest became literature relevant to both developed and developing countries.

I published Images of the Raj: South Asia in the Literature of Empire in 1988 (London: Macmillan, New York: St. Martin’s Press). “This the first study of Raj literature from its origins in the age of Elizabeth I to the present [that is 1988]” [from the jacket text] really, a branching off from my major interest. Salman Rushdie (Macmillan, St. Martin’s, 1988, 2nd edition 2010) was a reaction to the worldwide interest in him since the fatwa and the need for an introductory book understand/appreciate a difficult writer hailed since Midnight’s Children (1981); and Sri Lankan English Literature and the Sri Lankan People 1917-2003 (Colombo: Vijitha Yapa, 2005, 2ndedition 2007), a response to the writing around me, and most significant of my works arising from my mission to bring Sri Lankan Literature to the notice of those in Sri Lanka and outside. I was recognised as “a major authority on British literature and the Commonwealth in general, and on Sri Lanka in particular.” [WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag: Trier, Germany.]

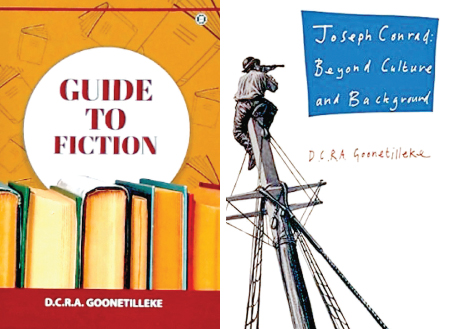

I have been a university teacher all my professional life, and it was natural that I should be concerned about students at G.C.E. O/L, A/L, and university – general readers, too – the first half of the book. Sarasavi published Guide to Literary Criticism. Guide to Poetry, and last year, Guide to Fiction – the first half of the book contains the full text of many (prescribed) outstanding stories, followed by comments to enhance understanding; the second half examines popular/celebrated (prescribed) novels.

Q: Can you share a particularly memorable or challenging piece of literary criticism you’ve written? Your in-depth research on Conrad is internationally recognised as a significant and outstanding contribution to English literature.

A: Yes. My particularly memorable and challenging literary criticism has been on the fiction of Joseph Conrad, contributions in a highly competitive and much-explored field. I published Joseph Conrad: Beyond Culture and Background (London Macmillan, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990), so far, the only full-length study of all Conrad’s fiction by a Third-World scholar.

The title of the book encapsulates the approach to Conrad I had reached. I invoked culture and background, and at the same time showed how incompletely these account for Conrad’s achievement. Conrad’s sceptical vision and concern for countries dominated from abroad derives in part from his multinational experience and probably from his Polish origins. Poland had no Empire and was, in fact, subject to Russian imperialism. As a Pole, he was at the receiving end of imperialism. I deviated from Leavis in judging Heart of Darkness, a masterpiece as from the days I was planning doctoral research. I included a chapter on it in my thesis, the book version, as well as in the full-length study.

Broadview Press invited me to edit Heart of Darkness so that the edition would be different from the Bedford/St. Martin’s as well as the Norton Critical which dominated the North American market. My edition (1995) was widely acclaimed, second edition in 1999, and a third in 2020, a Broadview bestseller, I was also invited to write a whole book – Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (Routledge, 2007).

Thanks mainly to Conrad, I was able to achieve an international standing. What made Heart of Darkness a masterpiece were the literary issues intrinsic to the novella (modernism) as well as the cultural, political and historical issues that pertained to 1900 and continue to affect us. Imperialism which is the context and an important part of its themes, is arguably the major historical phenomenon that has shaped the modern world.

When I became a Professor at the University of Kelaniya in 1980, with the cooperation of the staff, I included Conrad texts for undergraduates who offered English as their major subject as well as for those who opted for English as a minor. The prescribed texts were Heart of Darkness and The Secret Agent. The staff regarded me as best suited to teach Conrad!

Q: How has the landscape of literary criticism evolved over the years, and what impact has it had on the interpretation of literature?

A: In response to this question covering diverse Continents, diverse countries, and an extended period, I will content myself by writing on the results of exposure to literary criticism in the West of myself and other Sri Lankan academics.

Close reading, which has remained a permanent feature of literary criticism globally, is my basic procedure. I perform this task while seeing the literature in the context from which it emerged. I have remained committed to mainstream literature ever since my doctoral research in this field.

After the canon was interrogated and diversified to cater to special interests such as race, class, and gender, the present generation of academics often took the option of researching postcolonial literature for their doctorates. When they dominated Departments of English, postcolonial literature took centre stage, and mainstream, canonical literature was often backstage. Yet I, too, responded to the new movement, and included Post-colonial literature in my writing – notably on Ruth Prawer Jhabvala and Salman Rushdie, and on Vikram Seth and Romesh Gunasekera.

Q: As an emeritus professor and writer, what do you think are the most significant challenges in communicating complex literary theories to students or readers?

A: I do not pursue complex literary theories. I have gone my own way and major publishers in the West have accepted my work.

Q: As a writer and critic, how do you maintain the balance between objectivity in criticism and expressing your own subjective interpretations and opinions?

A: I believe subjectivity is most important. Literary criticism must be personal, or it is nothing. Yet subjective interpretations and opinions must be backed by objective reasons and illustrations from the given text/s.

Q: With the rise of digital media and online communities, how do you see the relationship between traditional academic literary criticism and popular discourse evolving?

A: I think the rise of digital media and online communities will widen readership, but the print versions of books will remain primary.

Q: Who are your favourite local and global writers?

A: My favourite global writers are Joseph Conrad and Salman Rushdie. My favourite Sri Lankan writers are Suvimalee Karunaratna and Ashok Ferrey.

Q: As an Emeritus professor, what advice would you offer aspiring literary critics and scholars entering the field today?

A: They must use the facilities available now: one can download the full text of articles and even whole books.

At the same time, one must not be led astray by interpretations of texts on the net because these are frequently erratic.

One must try to be up to date by regularly reading the Times Literary Supplement and the New York Review of Books. One must identify one’s own interests regarding future contrbutions and jot down ideas in these areas as these occur. As a result, when one comes to write, one does not start from scratch. Basically, one must enjoy one’s work.

A Ph.D. is not the summit of one’s career, but the beginning of one’s future work. It is important to choose a subject for doctoral research which will act as a springboard.