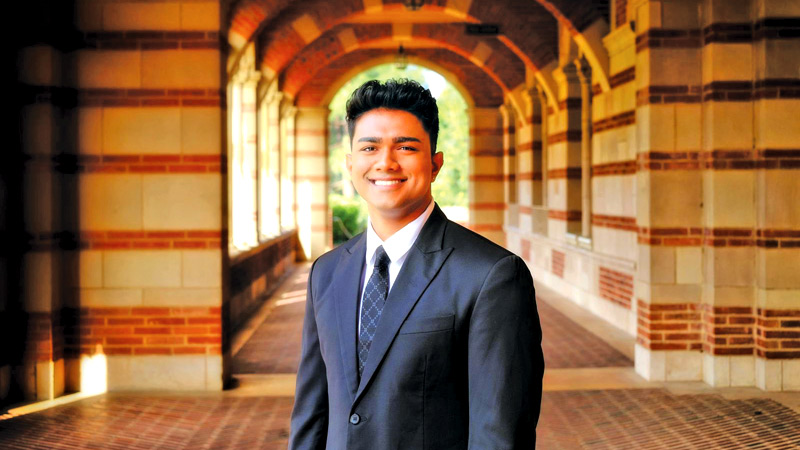

Youth Observer sat with Vipulesh Thiyagarajah, an entrepreneur, investor, and business strategy consultant who completed his Bachelor’s Degree at the University of California, Los Angeles and is the first-time author of the book Sonder.

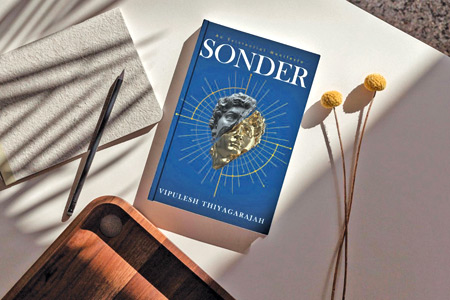

His book delves into existential themes, exploring how ideas, cultures, and societal constructs shape our understanding of happiness and the human experience. Drawing from his experiences in Sri Lanka, the West, and Africa, Vipulesh examines how different cultures approach life, happiness, and community. Through Sonder, he urges readers to question societal norms and pursue new experiences, emphasising the importance of personal growth and mental evolution.

His book delves into existential themes, exploring how ideas, cultures, and societal constructs shape our understanding of happiness and the human experience. Drawing from his experiences in Sri Lanka, the West, and Africa, Vipulesh examines how different cultures approach life, happiness, and community. Through Sonder, he urges readers to question societal norms and pursue new experiences, emphasising the importance of personal growth and mental evolution.

Q: What inspired you to write “Sonder” at such a young age?

A: I didn’t enjoy fiction much in my teens, but I started reading nonfiction and listening to podcasts over the years. I encountered various ideas; Sri Lankan values are entirely different from Western values, leading me to question what’s right and what’s not. In that process, I came across many scientific, philosophical, and psychological theories.

In my exploration, documenting these ideas would be a good idea. Sonder isn’t so much a story as it is a collection of ideas from all over the world, from 500 years ago to the present, and how these ideas have evolved, just as people, empires, and governments do. You become over your life, and this book reflects my five-year evolution. I decided to document it and compile it into a hefty book, and that’s how Sonder came to fruition.

Q: Can you share a personal experience that led you to explore existential topics like the pursuit of happiness and the hedonic treadmill?

Q: Can you share a personal experience that led you to explore existential topics like the pursuit of happiness and the hedonic treadmill?

A: It started with an understanding of social media. I was exploring where desires come from, leading me to Rene Girard’s theory of mimetic rivalry. We often desire things not because we genuinely want them but because someone else has them. This creates a sense of rivalry, and when it gets out of hand, it usually leads to conflict and, eventually, a scapegoat. We see this pattern in Sri Lankan politics: from British rule to the civil war, where instead of solving issues, we let them boil over, leading to regime shifts and ongoing conflict.

The divide between people has shrunk so much that everyone is aware of everything and wants to do everything. The level of desire has exceeded people’s capacity to fulfil it, leading to chronic unhappiness, depression, and anxiety at rates never seen before in history.

I went through a similar spiralwhen I was younger, constantly seeking new experiences, from flying planes to learning golf. It was a pursuit of novelty, but eventually, I realised it was essential to focus on experiences I genuinely wanted rather than what everyone else desired.

Arthur Brooks from Harvard University talks about an equation: satisfaction equals what you have divided by what you want. If you wish to exceed far what you have, your satisfaction will always be low. It’s about finding a balance;if you keep chasing after the next thing, you end up on the hedonic treadmill, where each additional consumption unit brings diminishing satisfaction. Your favourite slice of pizza makes you happy today, but eat it every day for a month, and you won’t want it anymore. So, you search for the next thing that will satisfy you more.

Arthur Brooks from Harvard University talks about an equation: satisfaction equals what you have divided by what you want. If you wish to exceed far what you have, your satisfaction will always be low. It’s about finding a balance;if you keep chasing after the next thing, you end up on the hedonic treadmill, where each additional consumption unit brings diminishing satisfaction. Your favourite slice of pizza makes you happy today, but eat it every day for a month, and you won’t want it anymore. So, you search for the next thing that will satisfy you more.

Eventually, you forget what it’s like to be content, losing your sense of normalcy. And when you can’t exceed that high anymore, you come crashing down.

Q: After all the research and identifying many more aspects of life, what has changed?

A: Researching for the book was a huge perspective shift, especially in terms of understanding life from various cultural angles. Having lived in Sri Lanka, the West, and even spent some time in Africa, I encountered vastly different perspectives and values. For example, in the West, the nuclear family or having children might not be seen as central to one’s life purpose, while in Sri Lanka, that’s often the whole point of life. But who’s necessarily happier?

Through this journey, I developed a deep appreciation for the value of companionship and community and began to understand the role social constructivism plays in our lives. We invented money to solve the barter problem, property ownership to prevent conflicts over land, and religion to unite communities rather than cause tension. Sports, similarly, bring people together, transcending differences in support of a common cause. These are all examples of social constructs that shape our world.

The research made me realise where I stand: financially, politically, within my community, and in relation to the environment. It gave me a deeper understanding of how everything around me influences my happiness more than anything I could do for myself.

I came across a theory about contagious happiness. If someone is rude to you in the morning and you interact with another person, that negative energy can be passed up to three degrees of separation. Conversely, a smile can have the same effect, spreading positivity. This interconnectedness means that the people you interact with, and even those they interact with, can impact your well-being.

How you live your life, what gives you meaning, and what you should pursue depend entirely on your perspective and perception, which are shaped by what’s around you, what you’re exposed to, and what you think. Social constructivism provides the ideas, mimetic theory feeds them, and your community dictates what you should want. How you grew up gives you your values and morals.

The book’s essence is about self-questioning and constantly reevaluating what one thinks is right. I believe humanity’s biggest downfall is complete certainty.

Q: How do you define happiness, and how has your understanding of happiness evolved?

A: Most people view happiness as a state you achieve once you get a fancy car, a house, and have a couple of kids, like, “boom,” you’re happy. But happiness is more like hunger or a headache; it comes and goes. If you were constantly happy, you’d never truly feel happiness. To experience pleasure, you need to experience pain.

Right now, people seem to have lost sight of the idea that to see light, you must also experience darkness. Suffering should be seen as lessons, as points of growth.

The goal isn’t to have constant highs but to maintain a state where you experience more high fluctuations than low ones. It’s not about avoiding homeostasis but maintaining it at a level better than the extreme highs and lows of chasing an exorbitant, lush life that may not bring true happiness.

It’s about finding the balance and understanding that even a simple life can be fruitful.

Q: How do you perceive the role of material wealth in achieving happiness?

A: The Grant Study, conducted by Robert Waldinger at Harvard, is the longest study in human history, spanning over 80 years. It included participants from all walks of life, different cultures, and various backgrounds.

At select intervals, the study measured what made these people happy and what didn’t. Interestingly, material wealth didn’t make presidents and billionaires happy. No matter how much wealth they accumulated, it never translated into happiness. Of course, if someone is starving or homeless, that’s a different issue altogether, but incremental wealth doesn’t contribute to their long-term happiness or prosperity.

The same went for their level of education;studying more didn’t make them happier. What contributed the most to their happiness was the community, not just a spouse or children, but a collective of people who supported them. This sense of community even translated into their health. People with supportive relationships tended to avoid bad habits like excessive drinking or drug use. Their cognitive capabilities remained high even at 80 or 90 because they constantly interacted with others.

On the other hand, those with poor relationships, such as those who experienced divorce or isolated themselves, often faced cognitive decline and developed poor habits. There was a quote from the study that stated, “Loneliness is a more deadly disease than smoking.”

Q: What is the most common misconception about the pursuit of happiness?

A: The problem is that people see happiness as an end goal, something they can achieve and then stop pursuing. But that’s not how it works. You can be a billionaire and still be miserable: many of them are. On the other hand, you can be a simple fisherman, catching a couple of fish, spending the evening with friends, and living an enjoyable life.

In Sapiens, we explore how humanity’s consciousness is our biggest curse. Unlike animals that follow their instincts, humans have the ability to think about the future and the past. This often leads us to worry about the future and let the past haunt us, causing us to forget about the present.

Before the agricultural and industrial revolutions, all we had to worry about was what we would eat tomorrow. Now we have so much to think about that we’ve become trapped, slaves of our success.

Bitcoin wasn’t a thing ten years ago, but now people are going bankrupt over it. Similarly, private property ownership wasn’t a familiar concept 200 years ago, and now everything is owned by someone or the state.

Our quality of life is better than kings who lived 200 years ago;they didn’t have hot showers, medicine, or anaesthesia. During World War II, soldiers had their limbs amputated without proper pain relief, whereas today, we can get shot and be fine after a hospital visit. Our quality of life has improved dramatically, but our mental state is declining rapidly.

This shows that we need to track what’s essential. Instead, we focus on minute details, the daily nitty-gritty, and lose sight of the bigger picture. I think Charlie Chaplin said, “Life in close-up is a tragedy, but in a zoomed-out lens, it’s a comedy.”

Q: What has been the most surprising realisation you’ve had while writing this book?

A: The most surprising realisation for me is that history follows a pattern; it’s not something that happens out of the blue. There are cycles, often around eight years, where similar events repeat. Just like in fashion, where old trends come back, history sees the same patterns, and generations reemerge.

For example, in the British Empire, the Roman Empire, and now the U.S.,we see how hegemonies rise and fall, and when they fall, there’s usually a period of conflict. During these cycles, there’s always an epidemic or pandemic, like Covid-19. Realising this pattern was quite surprising.

It would also be surprising to notice how the characteristics of each generation transfer over, especially in parenting styles. After World War II, parenting was very strict, raising a generation of tough, seasoned people. But over time, it became more relaxed, transitioning from soldiers to artists, and now we have Generation Z and Alpha, who are more creative. These cycles don’t just apply to parenting but also to societal conflicts.

Q: How do you personally cope with moments of existential crisis or doubt?

A: An existential crisis is about feeling aimless, not knowing where you’re going or what you’re doing. To overcome that, you need exposure and discovery. I’m at that point in my life right now. For most people, it’s about trying something different, like moving to a different country, quitting their job to start a new career, or even something as simple as dyeing their hair red. But what’s essential is not staying stagnant; it’s about searching for meaning. That’s the essence of existentialism: constantly trying to evolve, at least mentally.

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave (which I mentioned in the book) explains that everyone is chained and trapped in a cave, seeing only a few projections on the wall. The crux of the story is that once you escape the shackles of the cave and are exposed to the real world and the truth, it’s tough to go back into the cave and live in ignorance.

To cope with these challenges in my day-to-day life, I focus on constantly self-questioning. Being too sure of yourself and not allowing anything to change your thoughts or knowledge can be the biggest downfall. So, I strive to be ready to change and evolve. I avoid getting stuck in certain ideas that don’t necessarily mean much because they might not have originated from me, might not reflect what I truly believe, and might not be what will make me happy.

Q: If there was one message or lesson from “Sonder” that you want readers to take away, what would it be?

A: Pursue new experiences because you’ll never regret failing at something, but you’ll always regret never trying. Starting is probably the scariest part, but in retrospect, regret is a much harder pill to swallow than failure.