Whenever I head to historic places in the North Central Province such as Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, the Rangiri Dambulla Raja Maha Vihara is one of the must-see places in my itinerary. Situated on the Colombo-Anuradhapura highway, Dambulla is acknowledged as the most spectacular of Sri Lanka’s cave temples. One of the country’s World Heritage sites, Dambulla forms part of the Cultural Triangle, the UNESCO- sponsored project to safeguard and preserve ancient places of historical significance.

Whenever I head to historic places in the North Central Province such as Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, the Rangiri Dambulla Raja Maha Vihara is one of the must-see places in my itinerary. Situated on the Colombo-Anuradhapura highway, Dambulla is acknowledged as the most spectacular of Sri Lanka’s cave temples. One of the country’s World Heritage sites, Dambulla forms part of the Cultural Triangle, the UNESCO- sponsored project to safeguard and preserve ancient places of historical significance.

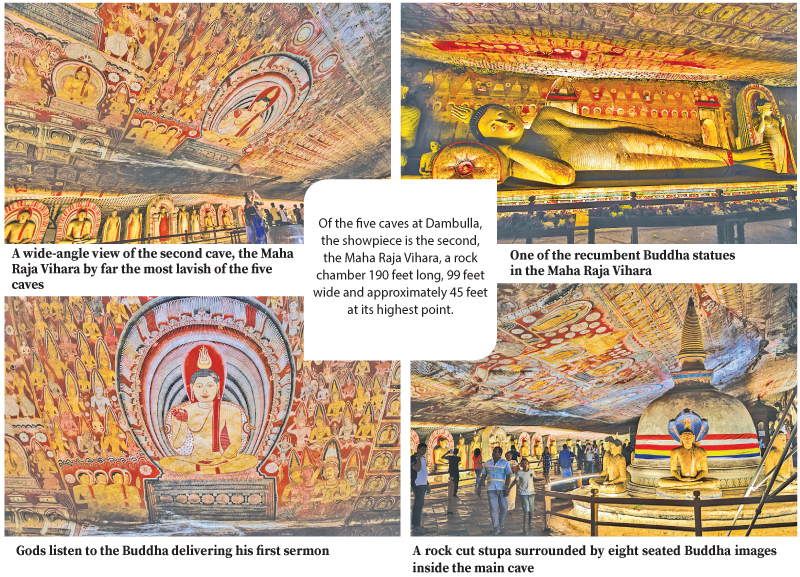

The picturesque site can be reached by climbing several rows of steps up to the big rock. The main cave is identified as ‘Maha Raja Vihara’ after the founder King Valagamba and is accepted as the architectural masterpiece of the complex. The setting inside is unique with a main Buddha image in the centre. The seated Buddha is under a ‘makara torana’ with attendant deities. On one side of the cave is a rock cut stupa surrounded by eight seated Buddha images.

Remarkable treasure

Sri Lanka’s most remarkable treasure of temple paintings is without doubt to be found in the Dambulla Rock Cave Temple, in a quintet of rocky caves dating from the first century BCE. A 600-foot-high rocky outcrop in the north central province, the Dambulla Rock Cave Temple consists of five continuous caves whose entire ceiling and wall surface is covered by paintings and painted – in all, a staggering 20,000 square feet of paintings.

The royal portraits are those of the three kings – Valagamba (Anuradhapura period, Nissanka Malla (Polonnaruwa period) and Kirti Sri Rajasingha (Kandyan period) – who have contributed immensely to make Dambulla such a treasured centre of Buddhist veneration.

Dambulla belongs to two important periods in Sri Lanka’s history; the troubled times of King Valagambahu in the first century BC when the shrine was first created and again to the 18th-century reign of King Kirti Sri Rajasingha who presided over a renaissance of culture and religion in Sri Lanka which included the renovation and restoration of Dambulla.

Maha Raja Vihara

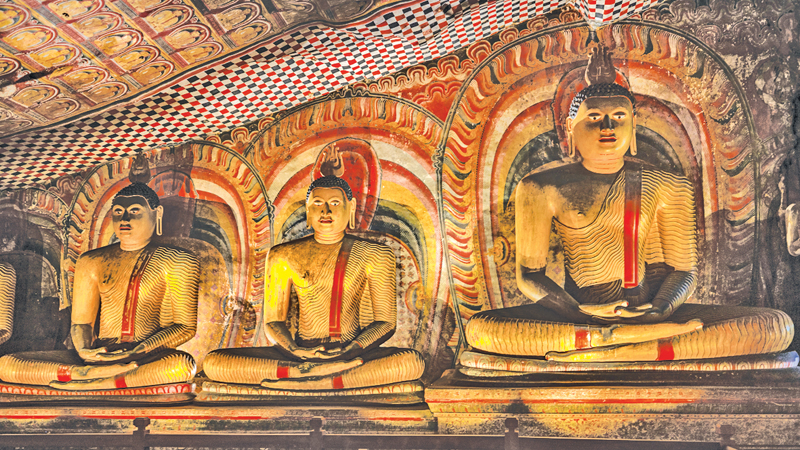

Of the five caves at Dambulla, the showpiece is the second, the Maha Raja Vihara, a rock chamber 190 feet long, 99 feet wide and approximately 45 feet at its highest point. This cave is lavished with a wealth of paintings depicting episodes from the life of the Buddha, incidents connected with the introduction of Buddhism to Sri Lanka, the Suvisi vivarana and also shows the cardinal developments in the attainment of Buddhahood – birth, renunciation, enlightenment and the passing away or the Parinirvana.

In addition, the paintings record the Buddha’s entire 40-odd ‘vas’ years, the seven weeks after Enlightenment, the first sermon delivered on an Esala Poya day to the gods and to his first five disciples and the defeat of Mara. These two episodes which are of great contrast to each other are painted within a gap of about 25 feet. Both compositions are of excellent quality and are among the masterpieces of Sinhala temple art.

Over a thousand Buddha figures have been painted in the caves. Ancient legend claims that the superb sculpture depicting the passing away of the Buddha was the work of Vishvakarma (a deity known for his perfect mastery of all skills and crafts), sent by the mighty God Sakra when King Valagambahu was in despair over the incompetence of his sculptors to portray the peace and fulfilment of the dying Buddha. This statue, in the first cave, is considered to be one of the best sculptured Buddha statues depicting the death of the Buddha.

18th Century restoration

The 18th-century restoration of the Dambulla paintings was carried out by a dynasty of highly skilled artists and specialist temple painters residing in the hamlet of Nilagama.

A section of this family, Jeevan Naide was the last set that restored the paintings in Dambulla. They used the original leather templates as well as rare formulas for the preparation of plaster and vegetable dyes used during the reign of King Kirti Sri Rajasingha.

These formulas used by the 18th-century craftsmen and artists are a fascinating demonstration of the use of indigenous natural materials mostly available in the surrounding environment. The only exception is vermillion which was imported to the island from India.

The rock surface for painting was made ready with the application of a first base undercoat prepared from white ceramic clay. This was sand dried, crushed, sifted and mixed with the slime obtained from soaking the peel of para fruit with gruel made from ground rice, embryo coconut, Kahata and bitternut bark. A binder of wild bees-honey was added to this coating. This undercoat was allowed to dry out for a week. A topcoat plaster of white mineral clay was then applied over this. This plaster was also dried out for a week to give a suitable hard surface for the painting. The prepared surface was then squared off with a network of drawn thread. Outlines were drawn in pale red dye made from imbul membrane.

Primary colours were all vegetable-base. Yellow was obtained from the resin of the gokuta tree common in the neighbouring Matale district. Blue dye was a more complex process. The green leaves of the blue avariya and bitternut were ground together and buried in the earth for six months, reground and mixed with mineral clay.

For black, the resin of yahakalu, dummala and the well-aged gum of the jak tree were ground together and roasted over a fire. The black, sooty deposit which formed on the earthenware cover was then made into an emulsion with woodapple latex.The emulsifying medium for all vegetable dyes and paints (except yellow) was in fact woodapple latex. Sculptures were polished with gokuta leaf glaze and finished by rubbing with cottonwood or a soft cloth.

The Dambulla murals are regarded as the best examples of the Kandyan period paintings as mentioned in ‘Medieval Sinhalese Art’ by Ananda Coomaraswamy: “The value of these paintings lies not merely in their beauty and charm as decoration but in the fact that they are priceless historical documents that could not be reproduced under modern conditions.”