After visiting the Dambulla rock cave temple, our next destination was Sigiriya, the 5th Century rock citadel, containing ruins of palace complex built by King Kasyapa (4774-4795 CE), has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The sight is stupendous even today: a massive monolith of red stone rises 600 feet from the green scrub jungle to accentuate the lucid blue of the sky. How overpowering, then, this rock fortress of Sigiriya must have been. When it was crowned as a palace 15 centuries ago!

After visiting the Dambulla rock cave temple, our next destination was Sigiriya, the 5th Century rock citadel, containing ruins of palace complex built by King Kasyapa (4774-4795 CE), has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The sight is stupendous even today: a massive monolith of red stone rises 600 feet from the green scrub jungle to accentuate the lucid blue of the sky. How overpowering, then, this rock fortress of Sigiriya must have been. When it was crowned as a palace 15 centuries ago!

Remarkable royal city

Sigiriya was gloomy and forbidding fortification, as many other citadels were. At the brief height of its glory – only 18 years in the late 15th Century – it was one of the most remarkable royal cities that ever graced the earth. And today, it holds unforgettable memories for visitors. Ruins of the famed palace spread across the very peak of the ‘Lion Rock’ – so-named, perhaps, because visitors formerly began the final harrowing ascent through the open jaws and throat (giriya) of the (Sinha) whose likeness was once sculpted half-way up the monolith. Only the gigantic paws remain today.

Sigiriya, the “Lion Rock’ seen through the western entrance

from the water garden

Within facade a grotto on Sigiriya’s west face, beautiful bare-breasted maidens still smile from incredible fresco paintings. Surrounding the foot of the rock, extending for several hundred metres are Asia’s oldest surviving landscape gardens, incorporating lovely ponds around Sigiriya’s plinth of fallen boulders.

The site of Sigiriya was known from ancient times. Inscriptions on boulders confirm that it was a hermitage for bhikkhus from an early date. Its importance as a seat of royalty began and ended in the last quarter of the 15th Century, under the direction of King Kasyapa – who conceived and perfected this masterpiece under a shadow of paranoiac fear.

Kasyapa was the eldest son of Anuradhapura’s King Dhatusena, the great tank builder. Fearing that he would be supplanted in the royal succession by his younger half-brother Mogallana – whose mother was of royal blood while Kasyapa’s was a commoner – Kasyapa seized the throne and imprisoned his father. Mogallan fled to India.

Kasyapa demanded that his father reveal the wealth he was convinced had been hidden. Dhatusena took the young usurper to the bund of the Kalawewa, the greatest of his irrigation works, below which lived a venerable bhikkhu who had been his teacher and companion many years. “There,” said Dhatusena, pointing, “are all the treasures that I possess.”

“Slay my father!” cried an outraged Kasyapa. The former king was walled alive within his tomb.

Fear, arrogance and a delusion of divinity drove Kasyapa to construct his palace on Sigiriya rock. Seven years after his ascent to the throne in 477 CE., Kasyapa moved into his fabulous new palace. Eleven years after, in 495, he descended from the impregnable stronghold to meet Mogallana who – returned from India with an army of combined Chola and Sinhalees troops – on the treacherous plains near the modern town of Habarana.

Defenceless

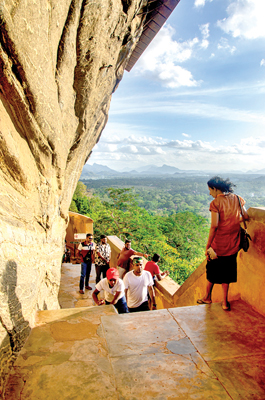

The pathway towards the rock’s summit leads from the Mirror Wall

At the height of battle, Kasyapa’s elephant, sensing a hidden swamp before him, momentarily turned aside. His army, fearing their leader had turned in retreat, broke in confusion. Kasyapa was left defenceless. Flamboyant to the last, he drew his dagger, cut his own throat, raised the blade high in the air and struck it back in its sheath before falling.

Mirror Wall

Although Mogallana immediately moved his capital back to Anuradhapura, Sigiriya was not instantly forgotten. For at least 500 years after the death of Kasyapa, sightseers scaled the citadel to gawk at the Sigiriya Maidens and admire the view. Sri Lanka’s oldest graffiti verifies this. Incised in tiny pearl-like script into the so-called ‘Mirror Wall,’ beneath the frescoes pocket, are prose and poems more than a1,000- years-old.

The Mirror Wall held the astonishing walkway called the ‘Gallery’ against the rock face. Visitors pass this route immediately after they have climbed the caged spiral staircase to the phenomenal frescoes pocket of the ‘Sigiriya Maidens.’

No one quite knows whom the seductive beauties, painted in tempera in brilliant colours on the rock wall, represent. It is easy to think of them as apsaras, heaven-dwelling nymphs from a realm of radiant light – above whom, perhaps, lived the ‘god-king’ in his rock-top palace.

Perhaps they were only ladies of the court on their way to the temple. The graffiti speaks of 500 ‘damsels’; there, are but only remain 18 today, protected from sun, wind and rain erosion in this sheltered grotto. In 1967, a vandal obliterated several of these priceless treasures. Fortunately, they were restored by Italian Dr. Marenzi sponsored by the Smithsonian Institute. The pathway towards the rock’s summit leads from the frescoes along the Mirror Wall and up to the ‘Lion Terrace.’ Bounded on three sides by a low parapet and on the fourth (the south) by a sheer cliff, it is a beautiful site.

Romantic architectural concept

The gigantic lion which once crouched here, half-emerged from his den, was a magnificently romantic architectural concept; the conceit of having the one path to the climax of this fantastic city lies through the jaws of the menacing beast provided an intimidating military advantage as well. Today, one merely climbs through two clawed paws to reach the steep stairwell and wind-blown steel railing that leads to the summit.

The Lion terrace’s portal ‘Sinha giriya’ to the summit

The entire summit of Sigiriya, nearly three acres in extent was occupied by buildings. Running water trickled through channels beneath the floor of the moated, colonnaded ‘Royal Summer House.’ Bathing pools were cut out of the living room. Below and to the east, a canopied divan or ‘throne’ was carved from naked rock.

Rock and water gardens

At the base of the rock are the fascinating rock and water gardens. Especially note one enormous ‘split boulder.’ On the half still standing, a water cistern has been cut. On the fallen half, a rock throne faces a square, leveled floor which may represent a council hall.

At the main western entrance to the Sigiriya compound, the ‘Water Garden’ beckons one. The symmetrically planned ponds may have been purely ornamental.

After many neglected centuries lost in the scrub jungle, Sigiriya was rediscovered by an incredulous British hunter in the mid-19th Century.

From 1982 to 1987, under UNESCO and the Cultural Triangle Project sponsorship, extensive digs and restoration were done. Finds have been exhibited at the small Archaeological Museum just west of the water garden, outside the main walls of the fortress.

As the tourism industry has been expanding rapidly, a large numbers of foreign and local visitors visit to witness the Sigiriya fortress on holidays and it has turned out to be a popular tourist hot spot for foreigners from all over the world.