“The future ain’t what it used to be” – Yogi Berra

With a new Government and renewed optimism for economic revival, the evolving trade, technological landscape, and shifting geo-economic features will likely alter developing country growth strategies, particularly export-led growth.

With a new Government and renewed optimism for economic revival, the evolving trade, technological landscape, and shifting geo-economic features will likely alter developing country growth strategies, particularly export-led growth.

Understanding these structural and geo-economic changes is a prerequisite for designing and pursuing effective development strategies, as an old, tried-and-true path for trade-assisted development may be challenging. I discuss these structural changes to the global economy as “facts of life” to consider in redesigning our growth strategies — whether industrial and export strategies and/or free trade agreements.

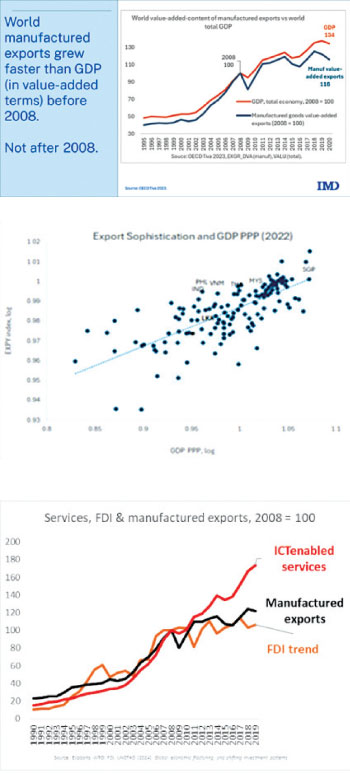

World manufacturing trade is plateauing: As a reflection of global demand, between 1990 and 2008, manufacturing exports worldwide grew dramatically. Growth of domestic value-added embodied in manufactured exports (i.e., export-led growth) grew faster than GDP with the rapid expansion of global value chains (GVCs).

Most developing nations, including Sri Lanka, had their successes in transitioning out of agriculture and commodity exports towards manufacturing-oriented growth, creating job opportunities, especially for women. However, since 2008, manufacturing exports have plateaued and are now growing with GDP, and foreign direct investment (FDI) manufacturing has stagnated. Manufacturing employment, too, has been declining across much of the world.

Sri Lanka has mirrored global trends. It missed an opportunity to establish a presence in GVCs when the competition was less fierce. Its rank in UNCTAD’s Competitive Industrial Performance Index has declined since 2000. Sri Lanka’s manufacturing exports remain heavily reliant on low-tech production (except high-end garments, auto parts, airplane parts, and a few niche outliers), lacking the technological depth to affect productivity significantly.

The service sector is emerging as a major driver of trade: Services trade, including commercial services such as ICT and business services, is becoming a key driver of global trade growth, reflecting world demand and mimicking growth rates comparable to those in manufacturing in the 1990s and early 2000s. A significant proportion of service trade occurs between businesses (B2B) rather than directly to consumers. B2B services include tasks across sectors like manufacturing, other services, and agriculture that support operations but are not sold to customers, such as bookkeeping, forensic accounting, and administrative functions, which remain labor-intensive and continue to thrive. International FDI, too, has shifted significantly towards services; as highlighted in the UNCTAD World Investment Report between 2010 and 2022, approximately two-thirds of global FDI flows were directed to the service sector (digital, finance, and telecommunications), while only about a quarter went to manufacturing.

Sri Lanka’s commercial services have recorded the highest export growth in recent years, especially in ICT, transport, and travel. Sri Lanka’s productivity levels in the services sector are higher than in the industrial sector and have grown significantly over the past decade. Workers moving out of agriculture or manufacturing are becoming more productive in the services sector, especially tourism.

Technology is rapidly changing manufacturing processes: Automation and robotics are reshaping the dynamics of export-led growth in manufacturing by reducing the emphasis on labour costs, which has traditionally been developing countries’ comparative advantage. As automation becomes more widespread, manufacturing processes become less labour-intensive and more geographically localised, diminishing job creation prospects.

Meanwhile, digital technology is making service sector jobs more tradable, enabling developing countries, with their relatively abundant capacity, to tap into underpriced service exports and rising demand in developed and large developing markets, presenting a significant opportunity for developing countries.

The new and continuously evolving global economic order requires a thoughtful assessment of which policies can best enable Sri Lanka to adapt to these shifts and mitigate the risks associated with ill-considered bets. While an export-led path is conducive to generating sustainable growth and job creation, yesterday’s policy framework requires more than a refresh but a rethink.

While manufacturing opportunities remain, especially as China moves away from labor-intensive activities and global trade and geopolitical shifts reshape value chains, realising these opportunities depends on Sri Lanka’s ability to implement structural reforms swiftly, without which Sri Lanka’s window for leveraging manufacturing exports for growth could rapidly diminish.

Therefore, the evolving global trade and technology landscape necessitates considering alternative paths to export-led growth. As digital technologies drive the expansion of service exports, especially untapped prospects in commercial services (which also provide an alternative entry into global value chains), due consideration must be given to the broader range of opportunities across industries, including inclusive of services and agribusiness that match Sri Lanka’s evolving comparative advantage.

Dr. Nihal Pitigala

As Sri Lanka looks to its future development path beyond the horizon of a single election cycle, careful consideration must be given to the evolving global trends and their impact on Sri Lanka’s development options — and, in turn, the optimal structure for a cohesive set of industrial, trade and investment policies, and trade integration policies that can help Sri Lanka navigate the new global economy.