Academic debates on understanding Russia as a distinct civilisation devoid of both Western and Eastern grip has been frequent. In writing his celebrated thesis ‘The Clash of the Civilisations’, Samuel Huntington describes Russia as a unique civilisation which is neither Western nor Oriental.

Russia’s tryst with the West dates back to the reforms made by Peter the Great in the 18th century who was fascinated with the enlightenment of the Western world, but none of his administrative or social changes could obliterate Russia’s link to the East which had imbued with the Russian way of thinking for centuries. The sui genris status Russia owns is essentially attributed to the way of thinking of Russia, which palpably differs from the West and the Russian attitude towards life resembles the Buddhist outlook on life. There has not been much of an academic inquiry in examining what impetuses played in Russian minds to view life as a gloomy, lamentable phenomenon, which is a stark contrast to their Western counterparts.

Russian interest in Buddhism

Russia’s scholarly interest in Buddhism continued to intensify in the mid-19th century mainly due to the German translations of Sanskrit and Pali Classics read by Russian intellectuals. This interest was not akin to the West’s preconceived notion of the Orient as many of the Russian orientalists were genuinely aspired by the wisdom of the East. The19th-century academic resurgence that pervaded Russian academia parallel to the development of the Slavophile movement dramatically impacted the study of Indology. When Max Muller’s Aryan thesis buttressed the colonial superiority of the British administrators in India, the subsequent institutes arose such as Asiatic societies embodied the legitimisation of the imperial needs as the cultural curiosity among the colonialists placed them superior to the subjects. However, the quest that sprang from the Russian Indologists in the later 19th and early 20th centuries freed them from such an avarice for colonial expansion of the state.

Contributions made by two Russian Indologists in the late 19th and early 20 centuries deserve special appraisal as their efforts elevated the study of Buddhism in India to a new juncture, which paved the path for other scholars to divert their studies into different avenues. The first significant Russian Indologist in the line of fame was Ivan Minayev (1840-1890). Within the short span of his life, Minayev’s penchant for Indian religions, particularly Buddhism was remarkable.

Contributions made by two Russian Indologists in the late 19th and early 20 centuries deserve special appraisal as their efforts elevated the study of Buddhism in India to a new juncture, which paved the path for other scholars to divert their studies into different avenues. The first significant Russian Indologist in the line of fame was Ivan Minayev (1840-1890). Within the short span of his life, Minayev’s penchant for Indian religions, particularly Buddhism was remarkable.

Institutional history

After having trained by Russia’s prominent Sinologist Vasily Vasiliev at St. Petersburg University, Minayev opted for Indology and his interpretation of the history of Buddhism in India was not merely confined to a rudimentary study in tracing its institutional history as Minayev insisted the need to study Pali, the canonical language of Theravada Buddhism in understanding its text.

The socio-cultural development under British rule that he witnessed during his travel in India, Nepal and Ceylon were recorded in his travelogues, which contained an array of details critiquing the British approach to understand ancient India. Moreover, Minayev’s greatest contribution to Indology was his work on the phonetics and morphology of the Pali language, which was later translated into many languages such as English, German and French. His writings on the importance of the Pali language to study Buddhism awakened many European Indologists and he was almost the first Orientalist, who took such a stance in Pali. It can be argued that the seeds planted by Minayev enticed many later Indologists to conduct more serious works in the fervent connectivity between Pali and the study of Buddhism, especially Sri Lanka’s greatest polymath of the 20th Century, Ananda Coomaraswamy had widely cited Minayev in several of his works on the Pali language and Buddhism

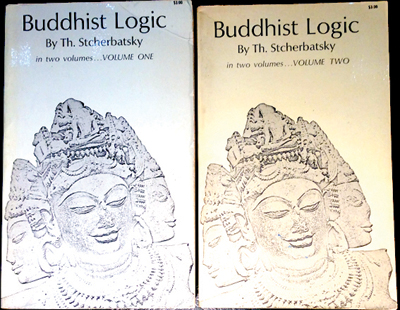

Fyodor Shcherbatskoy was another distinguished Russian Indologist whose scholarly contributions were impeccable in the study of Buddhism in India. Following the paths of Minayev, Shcherbatskoy spent a considerable period in India, which largely carved his training and he was one of the first scholars to imply the term ‘Buddhist Logic’ to refer to the Indian tradition of inference (Anumana), epistemology (Pramana) and science of causes (Hetu Vidya). In his much-celebrated work ‘Buddhist Logic’ published in 1930, Shcherbatskoy refuted the common myth in European academic circles in accepting Western hegemony in the positivistic philosophy.

While introducing the basic tenets of Buddhist logic, he unfolded how the system developed by Dignaga and Dharmakirti contained a coherent system of syllogism and for that reason alone deserves the title of logic. As a translator, who continued to translate many Pali and Sanskrit texts into Russian, Stcherbatsky followed a method that he called, the philosophical method as against the philological method of literal or word-to-word translation.

He was one of the first European scholars to single out Sanskrit philosophical texts as a special gender of Sanskrit Literature. His admiration of his favourite Indian philosopher, Dharmakeerthi made him regard the latter as Indian Kant. Though eloquent was his admiration for both Dharmakeerthi and Kant, such a description has not even a figurative value for those for whom Kant is not the measure of philosophical greatness. Taken in its literal sense, it is likely to interfere with an objective understanding of Dharmakeerthi’s actual philosophical position in its concrete context.

Legitimate roots

Both Minayev and Stcherbatsky truly committed to the studies in Buddhism driven by a knack to trace the legitimate roots of the subject and devoid of any preconceived prejudice on the Indic culture. The enthusiasm shown by the two reflects Russia’s intellectual stance in the East and it is a sheer contrast to the romanticised version propounded by Edward Said who described the vocation of an Orientalist as a storyteller legitimising the prejudices of the Westerner’s mind. However, examining the robust development in Russia in Buddhist studies and the trajectories that set the causes affirm the candid nature of Russian reading of Buddhism, which resulted in making greater contributions to the discipline.

The writer is a lecturer at the Department of International Law, Faculty of Law, General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University