The stretch of mountains expanding to the east ends in a deep slope. There are huge rock boulders all over the mountains. When one sees them with their natural caves through the shade of mighty trees, one gets the feeling of a calm dwelling that brings tranquility to both the mind and body. Because of the water that flows down from the summit, it is suitable for a quiet and peaceful life. There is no place more suitable than this for a bhikkhu leading an ascetic life. There are ponds too filled with pure crystal-clear water.

The stretch of mountains expanding to the east ends in a deep slope. There are huge rock boulders all over the mountains. When one sees them with their natural caves through the shade of mighty trees, one gets the feeling of a calm dwelling that brings tranquility to both the mind and body. Because of the water that flows down from the summit, it is suitable for a quiet and peaceful life. There is no place more suitable than this for a bhikkhu leading an ascetic life. There are ponds too filled with pure crystal-clear water.

Breathtaking view

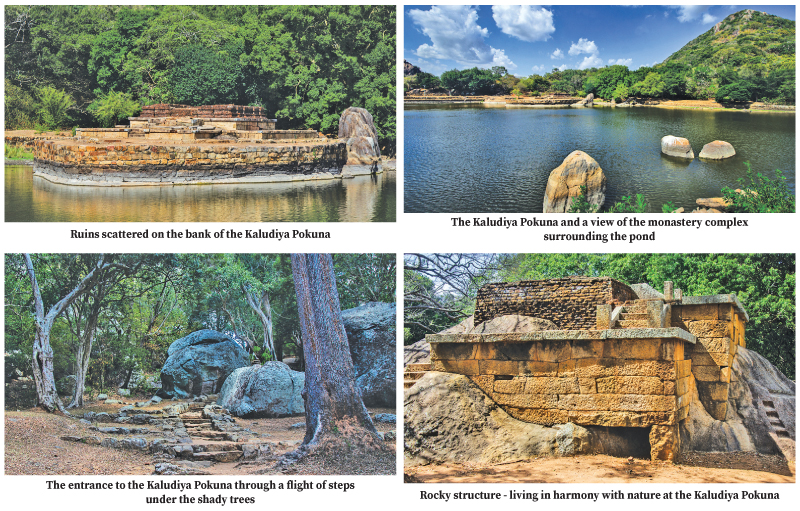

Ascending a staircase made of stone steps bordered by shady trees, we alighted at the Kaludiya Pokuna or the Black Water Pond, which is 200 feet long and 70 feet wide. Ruins of an ancient monastery scattered around the pond greeted our curious eyes. Once called the ‘Hadayunha Vihara,’ the monastery is considered to be a donation from King Kashyapa.

A glance towards the pond revealed the breathtaking view of a mountain mirrored in its dark surface. Looking above, the mountains towered towards the sky encasing this waterbody in its midst. After visiting Kantaka Chaitiya, we were at the Kaludiya Pokuna in Mihintale pursuing the secrets hidden in its murky depths.

The Kaludiya Pokuna is near the Rajagirilena Kanda in Mihintale. When coming from Anuradhapura and cruising along the Kandy-Jaffna Highway, take the left and the site is situated on the left-hand side.

Shrouded in an atmosphere of utter stillness imbued with an intangible air of mystery of a beautiful pond, which is rock-hewn, Kaludiya Pokuna as its name implies, (kaludiya translating to ‘black water’ and pokuna to ‘pool’ or ‘pond’) has dark water even on the brightest of days, shrouded as it is by trees and bushes and cupped by dark granite.

To our left we observed an olden dagaba that stood perched atop a landing. Made out of brick, only the dome has stood the test of time. Stepping through a stone archway that showed signs of having been part of an ancient rampart a little farther ahead, we strode along the length of a gravel path lined with grass, at points straying towards the pond where stone steps lead down to the dark waters. On the other side of the pond were ruins of a building made out of brick that rested in the midst of the pond. Certain experts surmise that this pond was used as a place to observe ‘pohoya karma’ (cardinal tenets) and the building in the midst is a ‘pohoya gey’ (chapter house). Begging to differ from this point of view, others point out that the space could have been utilised as an infirmary to care for afflicted bhikkhus.

Bhikkhu retreat

Surrounding all these structures and spread throughout a vast space were caves that were difficult to access. However, one cave close by gave a glimpse of an abode that might have been accommodated by bhikkhus during the Anuradhapura era. The entrance and the windows was decorated with simple yet intriguing frames, made out of stone with faint carvings. Inside the floor cave was smooth and showcased the dedication put forth in maintaining a comfortable living space. It is considered that though originally only Mihintale was dedicated to monastic bhikkhus with 68 caves, more areas such as Kaludiya Pokuna were employed to accommodate the increasing numbers during the bhikkhu rainy season retreats.

Kaludiya Pokuna was undoubtedly a place for spiritual exertions and this is established by the presence of a padhanaghara in the south west of the Kaludiya Pokuna. Tracing our steps towards a rock, where a flight carved steps led to the top of a rock boulder, we clambered up to catch the impressions of the Kaludiya Pokuna in the harsh rays of the afternoon sun.

Even today, following the ancient rituals of ascetic bhikkhus in the bygone era, the present monastic bhikkhus of the Kaludiya Pokuna Aranya Senasanay too use the waters of the Kaludiya Pokuna for their daily requirements. This Buddhist hermitage lies in the forested hill adjoining to the Kaludiya Pokuna monastery complex.

The above is a scanty description of the Kaludiya Pokuna monuments found in Mihintale. But there may be many more such monuments buried under the earth, yet to be discovered. Therefore, the story of Mihintale can never be completely told. It is the story of the Sinhala people that will be told perhaps for many more centuries to come, with new evidence coming to light.