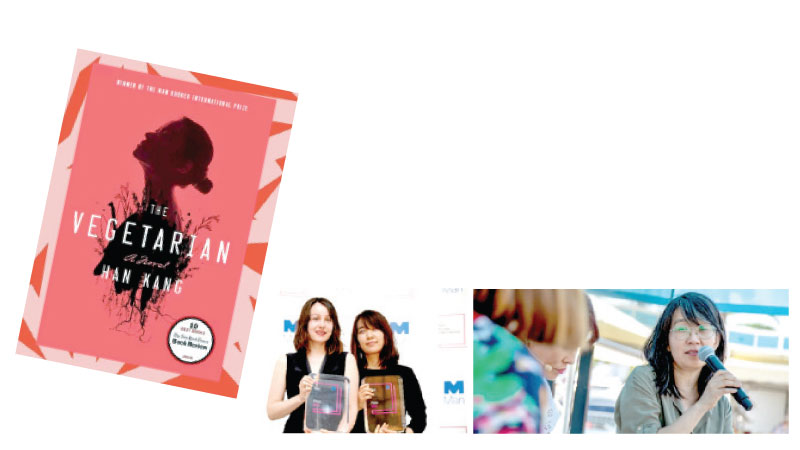

South Korean novelist Han Kang has won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature, celebrated for her poetic prose that depict historical traumas and the fragility of human existence. Han’s works include The Vegetarian, The White Book, Human Acts, and Greek Lessons.

With The Vegetarian, which won the Man Booker International Prize, Han established herself as an author willing to expose societal tensions and the frailties of human experience. Her Nobel Prize win has brought wider global recognition to Korean literature. It positioned Kang as the first Asian woman and first South Korean to win the award.

The Vegetarian epitomises the themes of grief, violence, sexuality, and mental health. Han’s achievement is anticipated to bring global recognition to Korean literature as the first Asian woman and the first South Korean to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Turning point

The turning point where The Vegetarian transcends its literal narrative is when the protagonist, Yeong-hye, turns to vegetarianism. Her act is something of resistance—a symbolic rebellion against a society that tries to force upon her its normative expectations. She is married to a conservative husband who expects her to toe the line.

Deborah Smith’s no-nonsense translation of Kang’s original Korean goes as follows to portray the protagonist’s husband’s wording:

“Before my wife turned vegetarian, I’d always thought of her as completely unremarkable in every way. To be frank, the first time I met her I wasn’t even attracted to her. Middling height; bobbed hair neither long nor short; jaundiced, sickly-looking skin; somewhat prominent cheekbones; her timid, sallow aspect told me all I needed to know. As she came up to the table where I was waiting, I couldn’t help but notice her shoes – the plainest black shoes imaginable. And that walk of hers – neither fast nor slow, striding nor mincing.”

So we are told how Yeong-hye and her husband lead unremarkable lives in modern-day South Korea. Her husband’s ambitions are modest. His manners are stable. But Kang is patient and takes time to expose her feminist ideal. Unlike her husband, the wife seems quite unhappy with her life resigned to the monotony of her role. She performs her duties without enthusiasm. Something of a rupture occurs when Yeong-hye makes a decision.

She decides to become a vegetarian. In this choice, Han Kang draws parallels to the existential defiance seen in Paulo Coelho’s “Veronika Decides to Die”, where a seemingly small decision—simple on the surface—unmasks esoteric stakes. We gradually come to terms with Yeong-hye’s grounds for renouncing meat. It is not merely a dietary shift but a rejection of societal norms and expectations. The world she is hell-bent on leaving behind is fleshly hence violent. Plus, it challenges the rigid structures of patriarchy and cultural conformity around her. However, the most interesting factor comes up later. Her choice spirals into a much deeper quest.

Transforming metaphors

Yeong-hye begins to entertain disturbing fantasies. She imagines discarding the demands and desires of her body, seeking transformation into something beyond human. The metaphors include a tree, rooted and tranquil. This physical and mental transformation that grows in Yeon-hye alarm, and even intimidate, those around her. She grows a seemingly impossible desire to dissolve her human identity and find ecstasy in unity with nature. This Kafkaesque metamorphosis wreaks havoc on her relationships and tests those closest to her.

The novel runs in three point-of-view sections. The first section tells Yeong-hye’s husband’s story in first person narrative. The second section tells Yeong-hye’s brother-in-law’s story in third person narrative. The third section takes us to Yeong-hye’s sister’s world in the third person narrative. As we move halfway across, we realise why Kang makes use of vegetarianism as a metaphor to weave her plot. Vegetarianism helps Han Kang draw attention to the dual nature of ethical movements. Vegetarianism is associated with compassion, but here is a South Korean author who invites us to question whether certain ethical stances have evolved into expressions of pseudo-cultural elitism. This lifestyle choice can sometimes mask a chauvinistic urge to judge the rest of the omnivorous humanity as barbaric.

Meat-eating reflects humanity’s conservative choice to fall in line with its natural omnivorous inheritance. In The Vegetarian, it becomes a metaphor for escape, resistance, and the longing to transcend societal shackles. Yeong-hye undergoes a psychological unravelling through her refusal to conform to dietary expectations. She chooses to opt out of a simple lifestyle custom. That said, Yeong-hye finds a path toward self-annihilation in vegetarianism.

This writer reads Han Kang’s novel as a critique on how acts of compassion or ethical superiority can create a divide; how compassionate choices can be transformed into tools of judgment. Digital platforms amplify this pseudo-elitism: lifestyles are broadcast, followed, and scrutinised on social media. The acts of compassion and environmental consciousness, quite performative on surface, cultivate a hierarchy of ethics where a particular lifestyle is praised as morally superior. One may wonder if this kind of acts promote any kind of unity. It feeds separation and alienates those who either choose different ethical paths or lack the means to follow ‘approved’ lifestyles.

Modern spirituality

Let us, however, not forget Yeong-hye’s rejection of meat is also an attempt to reconnect with a primordial innocence, an indigenous spirituality that modern life has severed. She becomes one with nature, her desire to transform into a plant symbolising a retreat to a pre-industrial, harmonious state of being. She reminds us of the inherent human connection to the environment—a connection increasingly ignored as society prioritises technological advancement and consumerism over traditional ecological wisdom. Her narrative serves as an elegy for indigenous knowledge systems that valued life holistically rather than instrumentally. It invites us to compare and contrast this worldview with the alienation caused by technological culture.

Cultural diversity and indigenous perspectives are flattened or overlooked by global, homogeneous narratives shaped by algorithms. Content is streamlined mostly for virality. Indigenous themes have become tokenised rather than genuinely appreciated. This algorithmic cultural dominance alienates people from authentic self-expression, as content is increasingly manufactured to fit platform trends. Han Kang’s work – her protagonist – stands as a rebuke to this phenomenon. She urges us to rediscover the depth and diversity of indigenous wisdom.

The portrayal of a protagonist alienated by her own society takes us to the psychological cost of a world where technology mediates human connections.

The digital age presents a parallel to the psychological detachment Yeong-hye experiences. Just as she withdraws into herself, resisting societal expectations and familial pressures, modern people find themselves alienated by algorithmic cultures that prioritise conformity and profit over genuine human connections. Algorithms dictate what content we see, reinforcing our biases. As a result, we experience an existential disconnection from the world, one reminiscent of Yeong-hye’s emotional and psychological descent.

Kang’s portrayal of Yeong-hye as an alienated figure, therefore, serves as an exciting allegory for how algorithmic culture stifles authentic human connection.

Han Kang’s work ultimately calls for a reclamation of humanity’s core values: empathy, connection, and the celebration of diversity. We are but individuals reduced to data points. Our experiences are tailored by corporations rather than personal choice. Kang’s narrative is a reminder of the psychological cost of this reductionist approach.

Kang emphasises the need for an empathy that respects the complexity of individual journeys, rather than reducing them to stereotypes or moral hierarchies. In Yeong-hye’s journey, we see the consequences of ignoring this need: without genuine empathy and understanding. The individual is left isolated. The individual is forced into roles that deny their authentic self.

The alienating effects of algorithm-driven societies must be combatted. The humanity must cultivate spaces for authentic interaction and cultural appreciation. Literature, as demonstrated by Han Kang’s works, remains a powerful medium for such engagement. Kang reminds us that to preserve humanity’s richness and diversity. We must champion narratives that dig into personal, social, and cultural nuances—narratives that do not cater to algorithms but instead echo the entire spectrum of human experience.

Han Kang’s Nobel Prize win brings home the power of literature to challenge, unsettle, and provoke societal reflection. The Vegetarian reveals the contradictions in modern ethical stances, exposing the superficiality of pseudo-cultural elitism while confronting the alienating effects of a digitised, algorithm-driven society. Through Yeong-hye’s journey, Kang pushes us to examine our own role within a system that largely feed division and isolation (termed connection, ironically). The Vegetarian is our mirror that reveals societal fractures, and the map that leads us toward wholeness through empathy, authenticity, and a respect for the diverse cultural legacies that define humanity.

What’s really lost in Translation?

‘Poetry is what gets lost in translation’ is an aphorism attributed to Robert Frost. However, the quote doesn’t appear in Frost’s published works. The quote is often interpreted to mean that the meaning a reader derives from a poem rarely aligns with the writer’s original intent. Others suggest it reinforces the idea that poetry is inherently untranslatable.

Whatever its intended meaning, the idea seems to apply to The Vegetarian as well. Kang’s prose is known for its poetic quality. Written in Korean, it raises unique challenges for translation.

After The Vegetarian won the Man Booker International Prize, controversy sparked in South Korea. Several media outlets highlighted significant mistranslations in the English version. Some newspapers even published line-by-line comparisons to illustrate the deviations from the original text. Charse Yun, a bilingual scholar of Korean and English, referenced research presented at Ewha Womans University showing that 10.9 percent of the novel’s first section was mistranslated, while an additional 5.7 percent of the text was omitted.

In his assessment of the translation, Yun shared an opinion akin to that of Anton Ego in Ratatouille, seeking to bring a fresh critique to the translation’s accuracy:

“Indeed, while the number of mistranslations in The Vegetarian is much higher than one would expect from a professional translator, most of these errors are very minor and do little, if anything, to derail the plot. For example, English readers will simply glide over the fact that anbang, the main bedroom, is rendered as ‘living room’; likewise, few will know that dakdoritang is confused as ‘chicken and duck soup.’ No harm, no ‘fowl.’ In one case, the mistranslation actually makes the effect stronger. When Smith mistakes ‘arm’ (pal) for ‘foot’ (bal), Yeong-hye suddenly seems more brazen: ‘…she stretched out her foot and calmly pushed the door closed.’”

The Korea Herald quoted Deborah Smith who defended her approach at the Seoul International Book Fair:

“Award-winning translator Deborah Smith said Wednesday that staying faithful to the spirit of a text was her priority.

And the spirit that she tried to preserve in Han Kang’s “The Vegetarian” was one of “tenderness and terror at the same time, never too far one way, always this very perfect balance,” said Smith at a press conference held at the Seoul International Book Fair on Wednesday.”

However, Yun counters this, stating:

“What is more unfortunate is that Smith misidentifies the subjects of sentences. In several places, actions and dialogue are simply attributed to the wrong characters.” Yun elaborates further, emphasizing that the English translation includes embellishments absent in the original.

“It may apply, however, to the embellishments that Smith makes to the text. This is more jarring and difficult to show. To cite examples out of context is difficult, since it really has to be seen in comparison to the Korean in order to be believed. Page after page, Smith inserts adverbs, superlatives, and emphatic word choices that are simply not in the original.”

For example, where Han’s original description simply notes that the protagonist’s husband didn’t consider his wife “anything special,” Smith rendered it as “completely unremarkable in every way.” When the husband speaks of an unwelcome “change” in his life, Smith intensified it to an “appalling change.” These examples reflect Yun’s concerns about interpretive liberties that diverge from the text’s subtlety.

In a 2014 interview with Allie Park, Smith shared her perspective on this topic:

“In my opinion – and this is an opinion shared by the vast majority of Anglophone translators, i.e., those who translate into English and also, crucially, are based in the Anglophone world – ‘faithfulness’ is an outmoded, misleading and unhelpful concept when it comes to translation. The single thing my editor advised me to do when I was working on The Vegetarian was ‘take more liberties!’ and I was incredibly lucky to be working with an author, Han Kang, who believes that translation can be as much of an art as creative writing – though of course, they’re not the same.”

Smith’s words reflect a school of thought that values translation as a creative act, where conveying the emotional and thematic weight may justify certain deviations from literal accuracy. Kang, as the original author, endorsed this approach, indicating her openness to interpretation. Yet for scholars like Yun, the cumulative effect of these liberties risks misrepresenting the original work.

Whether one sees Smith’s choices as necessary artistic liberties or as departures that obscure the original, her work has introduced Han Kang’s novel to a broader audience, albeit with a slightly altered tone. Perhaps that’s what makes literary translation so captivating.

And so, as far as The Vegetarian is concerned, that solves the case.