The quote “Spirit of the poor” is romanticised too often, but you won’t last a day in this world without their service. Crossing the railroad tracks, I was warned to turn away; to save my soul, and a man stepped out of the shadows and tried to sell me some hard drugs.

Slums and shanty towns – we try to keep them out of sight and out of mind. But for cities, these urban borderlands are its very lifeblood. This is where your maids, handymen, short-order cooks and garbage men live. But the high-rise apartments are too lofty for the tin roofs below, but perfect for those amber sunsets.

Slums and shanty towns – we try to keep them out of sight and out of mind. But for cities, these urban borderlands are its very lifeblood. This is where your maids, handymen, short-order cooks and garbage men live. But the high-rise apartments are too lofty for the tin roofs below, but perfect for those amber sunsets.

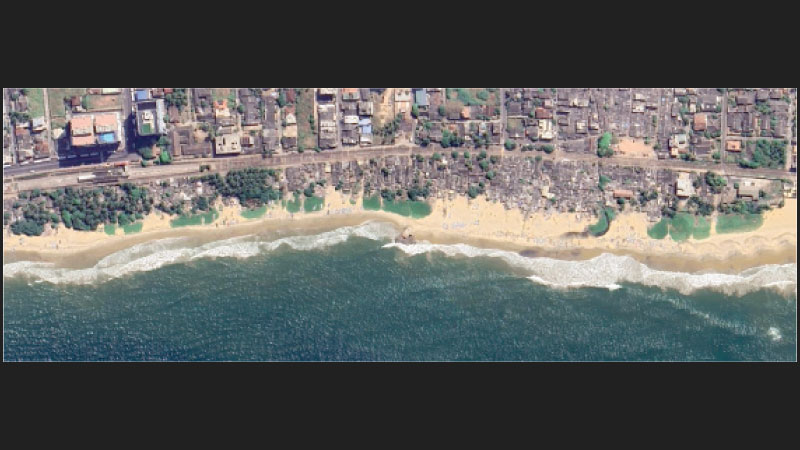

The fishing village on Dehiwela beach spans just under a kilometre; the trendy Mt. Lavinia beach lies to the South and the vibrant bars of Marine Drive to the North. To the East are tenement gardens — home to Colombo’s semi-impoverished with permanent addresses—bordered further by the Dehiwela – Mount suburbs and apartment complexes.

Old man and the Sea

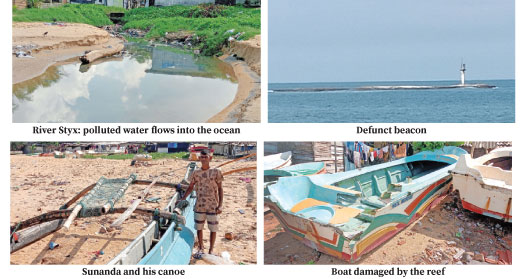

My contact introduces me to Salgadoge Dias – a veteran fisherman or a marakalahe (‘Captain’ in fisher-speech). “The sea is calm during the day but very rough during waarakanna season. We find it difficult to set out to sea because the light on the beacon hadn’t been replaced in a long time,” he said pointing to a tiny lighthouse-like structure on a reef 400 metres off the sea.

The waarakanna is held in equal measure of fear and reverence by these fishermen; the furious waves bring the fruits of the ocean.

It’s ironic how the Sri Lankan upper middle class flock to the Southern Coast during waarakanna; not to fish, but to rub shoulders with foreigners who need the same big swells and waves for their surfboards.

Dias said that boats crash into the reef frequently in the dark or topple over the shoal. “We lost two boats this year and people have died. We are constantly playing with death. If a proper breakwater is made, none of this will happen.”

I was shown a blue dinghy with its aft damaged after a particularly nasty accident with the reef.

He also said that commercial fishing has dealt a devastating blow to in-shore fishing. “Those big boats catch everything and we are left with very little,” he said adding that trawling is also done by foreign vessels that poach in Sri Lanka’s territorial waters.

He said he had seen Indian, Taiwanese and Korean fishing boats. Although Dias was right about foreign vessels poaching in Sri Lankan waters, it is doubtful that inshore fishermen witness any of these incidents – especially off the Colombo coast.

“We suffered a lot after the X-Press Pearl disaster in 2021. The beaches were littered with junk and we couldn’t fish for a long time. We were promised compensation but we still didn’t get anything. Even today, our nets are empty. We are catching nothing and it costs Rs. 25,000 to make a-one day fishing trip and we all pool our money to make these trips.”

According to the final report compiled by the Singapore Government, 11,000 metric tonnes of plastic pellets were spilled off the shore of Colombo. The report cited that the ensuing pollution brought on by the fire and subsequent sinking of the X-Press Pearl, caused an overwhelming economic, social and environmental impact. Additional information the UN report highlighted that epoxy resin is harmful to the environment and toxic to aquatic life and can have long lasting effect on marine fauna.

I, Robot

And there are some who embody the saying, “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.”

Robot is a scruffy young man in hoodie who knows all about scavenging. “The really good stuff is found on the beach during warakanna (The season when seas are rough),” he said carrying a shopping bag full of junk.

“My mom is dead. Dad is still alive. My brother is a drug addict and bugs me for cash. I don’t have money to buy a pair of slippers,” he said.

I have nothing and no one helps, Robot said. “Only if I can create a means of income; I’m a capable guy. I never harmed anybody. I need money, have no woman. My dad works in the night and there’s no food at home and when I’m hungry I ask around for food.”

Robot said that the bits and pieces he collects are stuff people need and added that he is the best scavenger in the area. “I find stuff, the others don’t find. My dad works in a plastic recycling truck and even they don’t find good stuff. I find the things people need and I give them to the people here.”

His bag had odds and ends. Umbrella poles, stainless steel ball chains and plastics among others.

Robot specialises in browsing the railroad tracks for junk. He said his territory starts from the Dehiwela railway station and ends in the first signal post. “What you find washed up is bottles and tree trunks. There is a season where things such as gold jewellery come floating in. This happens during the waarakanna and not harawa (The season when seas are calm).”

He spoke about living a hand-to-mouth existence. For him, the rest of us have money in the bank and can draw from it when we want to eat.

He spoke about living a hand-to-mouth existence. For him, the rest of us have money in the bank and can draw from it when we want to eat.

Robot’s story is also a powerful juxtaposition of privilege versus poverty. As Colombo’s middle class youth do “Beach clean ups” and post on Instagram, there are young people out there in dirty hoodies picking up odds and ends to survive.

Sunanda’s story

My contact was walking around his light-blue outrigger canoe. “Someone had used this without my permission last night,” he said. Sunanda is also a fisherman, but like many others in the community, he has found work in the city finding it hard to support his family with traditional means.

He moonlights as a night-watchman and tinkerer. Being outspoken than his peers, Sunanda told me about how the community had been promised housing since the tsunami. “We have the documents to back our claims.

One plan proposed to settle us far from the beach which is redundant,” he said, adding that the common view is that people living in slums are stubborn squatters who can never be convinced to leave.

“Look at those buildings right next to where we live. Three of those block apartments is enough for us and please build them close to our livelihood.”

I asked Sunanda whether going into the tourism industry is a better option since the surrounding areas have made that transition. “The people running restaurants on the Mount Lavina beach were also traditional fishermen and they even take tourists on little fishing excursions,” he said.

I also noticed mounds of garbage strewn on the beach and a gutter discharging impure water into the ocean. One wouldn’t pay much notice, since squalor is the reality of living in a shanty town, but imagine if the Municipal Council didn’t send their garbage trucks or didn’t clean out the gutters in a neat Colombo suburb for a week. It would make front page headlines the next day. “It’s worse when we get hit by the maariyawa (the big swell). The sea water goes inland and floods all our homes,” he said.

The Dehiwela fisher-shanty town starkly reveals our failure as a society. While pundits and economic gurus may label the working poor as lazy, such judgments are nothing more than hollow rhetoric compared to the political hypocrisy that keeps communities like these struggling below the poverty line. Their frustrations are justified, yet there’s a quiet dignity in how they carry themselves, knowing that our so-called civilisation rests squarely on their shoulders.