It was March 2001; protests were rife in Kandy, a heady band of protesters was on its way to the Sri Dalada Maligawa shouting their displeasure and horror at the edict by Mullah Mohammed Omar, the leader of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. This latest outcry was a series of such that voiced the displeasure of the cultural desecration that was about to happen in Afghanistan. The centuries old Bamiyan Buddha statues were to be destroyed. Around the world, many voices and organisations joined in unison to find measures to avert this tragedy, but the Taliban leaders were adamant and the destruction was to go ahead as planned.

It was March 2001; protests were rife in Kandy, a heady band of protesters was on its way to the Sri Dalada Maligawa shouting their displeasure and horror at the edict by Mullah Mohammed Omar, the leader of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. This latest outcry was a series of such that voiced the displeasure of the cultural desecration that was about to happen in Afghanistan. The centuries old Bamiyan Buddha statues were to be destroyed. Around the world, many voices and organisations joined in unison to find measures to avert this tragedy, but the Taliban leaders were adamant and the destruction was to go ahead as planned.

A caravan of traders descended into the lush valley carrying wares from all across Asia. The evening twilight casted a soft pinkish glow around the valley and the mountain region of Bamiyan reverberated with the chaos of the oncoming traffic of the caravans. The caravans were laden with precious silks all the way from China and other goods ranging from teas, dyes, porcelains and perfumes.

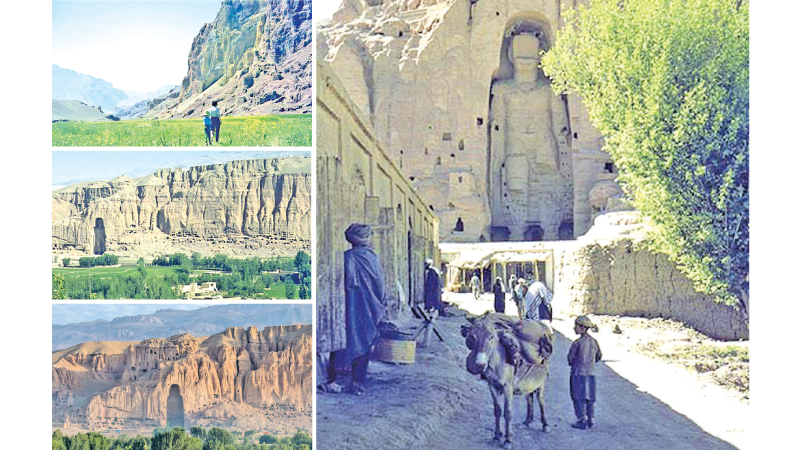

The surrounding plateau contrasted with the stupendous far-reaching Hindu Kush mountain peaks that came within their purview, they had arrived at the Bamiyan Valley, one of the central stops in the long arduous trek to their destination. Lying at an altitude of 8,366 feet, the valley separates the Hindu Kush mountains from the Koh-e Baba mountains. Located at the crossroads of the ancient silk route, the locale was brimming with activity, the prominent site merged the East with the West as traders moved along the valley dispersing along its many winding alleys. Overlooking this hype of activity was the gentle glance of the gargantuan sculptures of the multi-coloured Buddha carved into the surrounding mountain niches.

Human habitation in the Bamiyan Valley dates back to prehistoric times. The valley’s history spans over two millennia with archaeological findings suggesting that the area was settled by early human societies as far back as the Bronze Age. The region’s fertile lands, surrounded by the towering Hindu Kush Mountains, provided an ideal environment for early agricultural communities. By the first few centuries BCE, the region began to see more organised settlements, and the Bamiyan Valley emerged as a crossroads for various cultures. It became a key location for trade and cultural exchange, connecting the East and West via the Silk Road.

Kushana Empire and Buddhism

Bamiyan belonged to the Kushan Empire, after which the Empire fell to the Sassanids. Chinese bhikkhu Fa Hien travelled to Bamiyan during the fifth century and documented that the king called the bhikkhus of the area for vows and blessings. Fa Hien also wrote about landslides and avalanches in the mountains and the presence of snow during winter and summer. The latter report demonstrates climatic contrasts which could have contributed to the historical and economic significance of the site for the years to come. Another Buddhist visitor, Xuanzang, passed through Bamiyan in the seventh century. His record shows that the Bamiyan Buddhas and cave hermitages around it had already been constructed. He also documents that Buddhism in the area was in decline with the people being “hard and uncultivated.”

The Kushana Empire played a pivotal role in the spread and development of Buddhism throughout Central Asia and other parts of the Indian subcontinent. The Kushanas originated from the region around Afghanistan, Pakistan and China and controlled a vast empire starting from present day Afghanistan, Northern India and parts of Central Asia. The empire straddled the ancient Silk Route connecting the East and the West. This significantly contributed to the spread of Buddhism in the region and the arts and culture centred on Buddhism flourished in the region.

One of the main reasons the religion spread so rapidly was that the Kushana rulers were great adherents of Buddhism and fostered its growth. Kanishka is regarded as one of greatest kings of Buddhism and was one of its most notable patrons and is credited for convening the Fourth Buddhist Council around 100 CE, which was held to standardise Buddhist teachings and scriptures, especially in the wake of the division of Buddhism into different schisms.

The Kushana were instrumental in developing Buddhist art, and the Ghandhara style flourished during their time. This sculpture blended Greek sculptural traditions to depict the Buddha in human form, departing from the previously held symbolical representation. Greek influences were seen in the robes, facial features and body postures which were reminiscent of idealised depictions of the Greek gods.

The two stupendous Buddha statues were constructed in the 6th century CE during the reign of Kushana –Sasanian Kings who ruled the region. The statues were probably made under the patronage of the Kushana kings and stood alongside a crucial stop in the silk route where many traders gathered. These massive sculptures, most likely crafted by Greek sculptors standing at 180 feet sometimes called ‘Shamama’ Buddha while the smaller Buddha, Sakyamuni stood at 125 feet, were the largest Buddha statues the world had seen. Both statues were carved into cliffs of the Bamiyan Valley, the smaller statue represents the historical Buddha while the larger one was an image of Vairocana, the celestial Buddha, and a concept found in Mahayana Buddhism.

Spiritual serenity

The Buddha statues at Bamiyan exhibit serene, meditative faces with large almond shaped eyes, a common feature in Central Asia and Ghandara art. The spiritual serenity is enhanced by the realistic facial features, a result of syncretism influences in the region. Both were relief sculptures from the back and emerged from the mountain. The main bodies were hewn from sandstone cliffs, but details were shaped in mud and mixed with straw and coated with stucco. This coating was applied to the surface of the statue which was painted to enhance the features of the face, hands, and the drapery of the robes.

The larger statue was painted carmine red while the smaller one had multiple colours adorning the sculpture of which many have faded away overtime. Each statue was housed within a trilo bed niche whose arches were painted with coloured frescoes. Most of the exteriors in the cavity holding the Buddha were embellished with colourful frescoes, enveloping the Buddha with numerous illustrations, but only segments remained in modern times.

The 38-metre Eastern Buddha statue was constructed between 544 and 595 CE, while the main ceiling murals sit right over the crown of the Buddha. Some of the cave paintings are said to be much older than the sculptures themselves and was also the site of several Buddhist monasteries, and a centre for religion, art and philosophy. Bhikkhus at the monasteries lived as hermits in small caves carved into the side of the Bamyan cliffs. Most of these bhikkhus adorned their caves with religious statuary and detailed it brilliantly with coloured frescoes, disseminating the culture of Gandhara.

Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang visited Bamiyan on April 30, 630 and described the surrounding area as a popular Buddhist centre flourishing “with more than ten monasteries and a thousand bhikkhus.” He says that the sculptures of the Buddha were adorned with fine jewellery and even mentions a third statue, a large reclining one, much bigger than the standing sculpture. The travelling bhikkhu Fa-Hien passed through the valley in 400 BCE and made note of a ceremonial assembly of a thousand bhikkhus before the king and mentions relics of the Buddha being kept in Bamiyan, that of his tooth and his spittoon.

In Bamiyan, like everywhere else in Central Asia, tragedy stormed into the valley in the shape of Ghengis Khan in 1221 C.E. Ghengis Khan dispatched a small army to capture the valley, overseen by his favourite grandson. When he was slain by a bowshot from the fort of Shahr-i-Zohak, he swore implacable retribution: that neither human nor animal would be permitted to survive. He remained true to his word that either the city of Bamiyan or its frontiers were ever reconstructed; their devastations remain to this day as a testimonial to the human capacity for brutality.

Ghost town

The recovery was slow. Forty years following the disaster, Bamiyan was a ghost town and reconstruction took place in the 15th century, with the Timurid king; Babur, who had a sharp eye for untamed beauty was taken up with Bamiyan. The caravan interchange was sharply in decline. As an agrarian and rustic region, the gorge became a bastion of the Afghan monarchy; and ultimately captured the wandering gazes of a unique kind of traveller, the devout pilgrims. The magnet continued to be the monumental sculptures of the Buddha carved out on the mountain cliff standing tall and majestic inviting visitors to bask on the peace and compassion of the well-gone one.