Asoka’s existence would never have come to light and his edicts would never have been deciphered without the help of the Ceylonese monks from Sabaragamuwa province and George Turnour, the Ceylon Civil Service official who translated the Mahawansa with the help of the monks.

For almost 12 centuries, Indian chroniclers had blacked out Buddhist Emperor Asoka the Great, though he had ruled much of India from 270 BCE to 232 BCE.

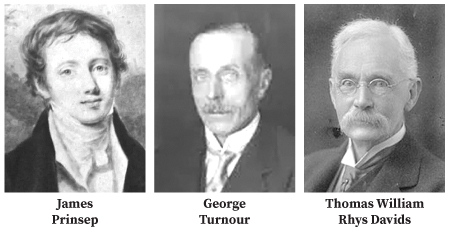

It wasn’t until 1813, that Asoka was pulled out of oblivion. That was done by two Englishmen, namely, archaeologist James Prinsep and Ceylon Civil Service official, George Turnour. They did so with the help of some learned bhikkhus from the Sabaragamuwa Province in Ceylon. Turnour had also secured from the bhikkhus some invaluable manuscripts which told the history of Ceylon and India.

Prinsep was able to read Asoka’s edicts in India, which were in Pali, with the help of Turnour and the monks. But Prinsep’s greatest discovery was the identification of “King Piyadassi” in the edicts as “Emperor Asoka”.

Prinsep was able to read Asoka’s edicts in India, which were in Pali, with the help of Turnour and the monks. But Prinsep’s greatest discovery was the identification of “King Piyadassi” in the edicts as “Emperor Asoka”.

Prinsep’s discovery was the first “re-birth” of Asoka. But the first rebirth did not create waves in India. Of course, archaeologists, Indologists and historians came to know of Emperor Asoka and plunged into further research. But Asoka was not yet a popular figure or a national icon on par with other great Indian rulers like Emperor Akbar. Buddhism, which he espoused had no takers then. The religion had vanished from India by the 14th century.

But fortunately, there was a second re-birth. This was when India became independent in 1947. Its first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, who was an ardent admirer of the Buddha, made it government policy to celebrate the birth of the Buddha every year as Buddha Jayanti. He wanted to rule India on the principles set out by Asoka. Like Asoka, Nehru wanted his India to be peaceful, tolerant, secular and progressive. Nehru adopted Asoka’s symbols, such as the Asoka Chakra and the Lion Capital, as the emblems of modern India. They have survived to this day.

Why was Asoka ignored?

According to Prof. T. W. Rhys Davids, a British historian and founder of the Pali Text Society in London, ancient Indian chronicles completely ignored Asoka because he was too radical for them (see: Buddhism in India (T.Fisher and Unwin, London, 1911).

In Rock Edict no: 1 to 12, Asoka spells out the main elements of his Dhamma (his term for Buddhism) which are antithetical to Brahminical Hinduism. He condemns people who perform rites for luck on occasions like sickness, weddings and childbirth or before going on journeys. These ceremonies are “worthless” he says. This cut the earnings of the priestly class, the Brahmins, who performed these rituals to earn their daily bread.

Asoka’s edicts disapprove of the practice of disparaging other sects or exalting one’s own. “Let a man seek growth in his own sect.” The edicts call for self-examination. This ill-fitted a hierarchical social system presided over by Brahmins. And lastly, there is not a word about God or soul. It is another matter that there is no word about Buddha or Buddhism either.

On the spread of Buddhism

On the spread of Buddhism, Asoka’s 13th Rock Edict says that Asoka’s Dhamma spread to Nepal, Tibet, Gandhara (now in Pakistan and Afghanistan), Burma, South India, Ceylon, Syria, Egypt and Macedon. This edict is engraved on a large rock in the Dhauli hills, near Jaugada, Odisha State, in Eastern India.

While there is no proof of the Dhamma spreading to the Middle East, the gifting of the Bodhi tree to Ceylon is sculpted very elaborately in the Sanchi stupa (in Madhya Pradesh, India ). In the sculptures depicting the gifting of the Bodhi tree to Ceylon, the lion represents Sri Lanka and the peacock (Mayur) represents the Mauryas, Asoka’s clan.

On the spreading of the Dhamma to Ceylon and its contribution to culture and history, Rhys Davids says that the mission to Ceylon was the climax of Asoka’s missionary efforts and the most fruitful. “The literature in Ceylon has taught us much of the history of religion, not only in Ceylon but also in India,” he said.

Other sources on Asoka

Rhys Davids got interested in Asoka because of his postings in Galle and Anuradhapura as an official of the Ceylon Civil Service. He learnt Pali, studied Buddhism and published papers on them while in Ceylon and continued to do so on return to England.

He said that there were four connected narratives on Asoka in India, Ceylon, Nepal and Burma which were also important sources on the history of Ceylon and India.

The first was the 3rd Century AD work, Asoka Avadaana (Asoka’s story), in Sansktit and preserved in Nepal. The second was the Dipavansa in Pali preserved in Burma. The third was an Indian bhikkhu Buddhaghosha’s commentary in Pali on Vinaya (a 4th or 5th Century document). And finally, there was the Mahawansa in Pali preserved in Ceylon.

The Mahawansa was a multi-volume poetic work, which covered 2000 years of Ceylon’s history during which 54 kings of the “Great Dynasty” (the Mahavansa) and 111 sovereigns of the Chulavansa or Lower Race, sat on the throne of Ceylon. George Turnour translated about 30 books of the Mahavansa and published them in 1836.

Pointing out the difficulties in deciphering the Asokan inscriptions, Rhys Davids said that, first of all, the inscriptions were scanty. “The text of all of them put together would barely occupy a score of pages in a book. There is also an economy of candour in some of these documents. They are an enigma.”

Referring to the tendency those days to condemn the Ceylon Chronicles as “mendacious fictions of unscrupulous bhikkhus”, Rhys Davids points out that the chronicles were not written by bhikkhus who were trained historians. They had written with the sources and analytical tools available at that time.

“We should actually be grateful for the way the bhikkhus had preserved what they got from imperfect sources,” Rhys Davids argues.

Asoka’s transformation

The Kalinga war saw the transformation of Asoka the warrior to a man of peace and reconciliation. In his edicts he says he follows the Dhamma, (his term for Buddhism). After he took to the Dhamma, Asoka ruled his vast Empire promoting peace and goodwill.

Asoka does not say who converted him or initiated him into Buddhism. He gives the impression that it was his decision unaided by anyone. He says that for two and a half years he was an Upasaka (lay disciple). Later he entered the Sangha or the order, and in the 13th year of his coronation (252 or 256 BC) he took to the Sambodhi or the Buddha’s Eightfold Path, hoping to be an Arahant.

About Asoka’s conversion Rhys Davids says: “It is strange for a king, whether in India or in Europe, to devote himself strenuously to the higher life at all. It is doubly strange that, in doing so, he should select a system of belief where salvation, independent of any belief in a soul lay in self-conquest. The result must have been due to his own character, his firmness of purpose, his strong individuality.”