A Global Biodiversity Hotspot

Being an island nation, Sri Lanka harbours exceptional biodiversity compared to countries of similar size. It has acquired recognition for key reasons such as distinct geographical location, climate, topography, and local geography. Although this land is home to numerous faunal and floral species, many are deeply threatened. This status has led to the recognition of Sri Lanka as one of the 36 global biodiversity hotspots along with the Western Ghats of India.

Being an island nation, Sri Lanka harbours exceptional biodiversity compared to countries of similar size. It has acquired recognition for key reasons such as distinct geographical location, climate, topography, and local geography. Although this land is home to numerous faunal and floral species, many are deeply threatened. This status has led to the recognition of Sri Lanka as one of the 36 global biodiversity hotspots along with the Western Ghats of India.

Megafauna: Icons of Biodiversity and Economic Significance

Five charismatic species, regarded as megafauna, namely elephants, leopards, sloth bears, blue whales, and dolphins, dominate the country’s biodiversity profile. Hence, they have acquired substantial attention and interest from key stakeholders such as tourists, policymakers, researchers, and conservationists. Most importantly, their contribution to the country’s tourism revenue is unmatchable to the other revenue streams.

Human Impacts

In contrast to the outstanding biodiversity status of the island nation, the other part of the story is quite disheartening. Many of its unique biota are deeply threatened. Human-led issues fast drive these species towards extinction. Climate change and global warming, habitat fragmentation, encroachments, and poaching are the threatening issues among many of the problems in the island nation. As a result of continuous pressure from humans, many of the species are threatened with extinction. Currently, the deer species are not recognised as the country’s megafauna. Therefore, it’s out of focus in many ecological studies and conservation initiatives. However, the issues this group of animals faces cannot be ignored due to their environmental importance.

Deer in Sri Lanka

There are four deer species in Sri Lanka: the Spotted Deer (Axis axis), the Sambar Deer (Rusa unicolour), the Barking Deer (Muntiacus muntjac), and the Hog Deer (Axis porcinus). The most common species is the Spotted Deer, distributed throughout the country except for the central highlands. Sambar and Barking Deer share an even distribution throughout the country. The latter species, the Hog Deer, is extremely rare and localised to certain parts of the country.

The Hog Deer

The Hog Deer, also known as Paddy-field Deer (Gona Muwa, Vill Muwa, and Wel Muwa in Sinhala), is a medium-sized ungulate that belongs to the family Cervidae. Due to its extreme rarity and localised distribution, when it appears, it is often misunderstood by the other deer species. As per the previous research studies, the distribution of the Hog Deer is restricted only to the south-western part of the country, mainly in the Galle district. Although seeing other deer species during excursions to the wilderness in Sri Lanka is common, sighting a Hog Deer is almost impossible, even in Galle. This may be due to its highly elusive nature and small population density. They mainly live in the Galle district’s home gardens, paddy fields, and secondary forest patches. They move from one area to another based on land availability. For instance, when the paddy is harvested, moving to a nearby cinnamon plantation or secondary forest would be an option. During paddy harvesting season, farmers find fawns lying in paddy fields. Sometimes, they make nesting areas in the paddy field when it is ready to be harvested. The grown paddy provides them with good cover and the wet conditions that Hog Deer prefer to stay in. However, this is a temporary behavioural state due to the shorter duration of the crop.

The Hog Deer, also known as Paddy-field Deer (Gona Muwa, Vill Muwa, and Wel Muwa in Sinhala), is a medium-sized ungulate that belongs to the family Cervidae. Due to its extreme rarity and localised distribution, when it appears, it is often misunderstood by the other deer species. As per the previous research studies, the distribution of the Hog Deer is restricted only to the south-western part of the country, mainly in the Galle district. Although seeing other deer species during excursions to the wilderness in Sri Lanka is common, sighting a Hog Deer is almost impossible, even in Galle. This may be due to its highly elusive nature and small population density. They mainly live in the Galle district’s home gardens, paddy fields, and secondary forest patches. They move from one area to another based on land availability. For instance, when the paddy is harvested, moving to a nearby cinnamon plantation or secondary forest would be an option. During paddy harvesting season, farmers find fawns lying in paddy fields. Sometimes, they make nesting areas in the paddy field when it is ready to be harvested. The grown paddy provides them with good cover and the wet conditions that Hog Deer prefer to stay in. However, this is a temporary behavioural state due to the shorter duration of the crop.

Threats to Hog Deer

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has designated the hog deer critically endangered (CR). Some records indicate that displaced fawns and injured adults were handed over to the nearby wildlife Veterinarian Offices in the Galle district.

A study conducted by Shashi Madhushanka for his postgraduate research study at the University of Peradeniya discovered that the most serious problem Hog Deer faces in the region is electrocution from illegal electric wires. Hunters and landowners place these wires to kill vertebrate pest species such as wild boars and porcupines entering their crop fields. However, Hog Deer accidentally hit these wires. Further, shooting them for meat continues. Sometimes, farmers don’t like them since they feed on young cinnamon saplings, which leads to reduced yield. All these reasons have negatively affected their survival in the area.

Hog Deer Conservation

Many questions remain unanswered about the country’s Hog Deer and ecology. Their origin, population size, habitat preference, and how they survive under enormous human pressures have remained a mystery for a more extended period.

Installed camera traps in the field.

Due to human activities, conserving this animal in its natural habitat would not be easy. Maybe introducing them to a new suitable habitat would be an option, but this is subject to a comprehensive understanding of its ecology. Any in-situ conservation measure should be coupled with raising community awareness.

Hog Deer Ecology and Conservation Project, Sri Lanka (HoDEC-lk)

The HoDEC-lk is an initiative of the Ecological Association of Sri Lanka (EASL). The project’s collaborating partners are the Conservation Ecology Centre, the Smithsonian’s National Zoo, and the Conservation Biology Institute.

In the initial stage, field cameras are being deployed in the country’s south-western part to study the population aspects, density, home range, and breeding information. The HoDEC-lk would be the first-ever camera trapping study conducted for Hog Deer in Sri Lanka.

The HoDEC-lk would like to thank the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) for financing this project with an internal Species Survival Commission (SSC) grant.

HoDEC-lk Team

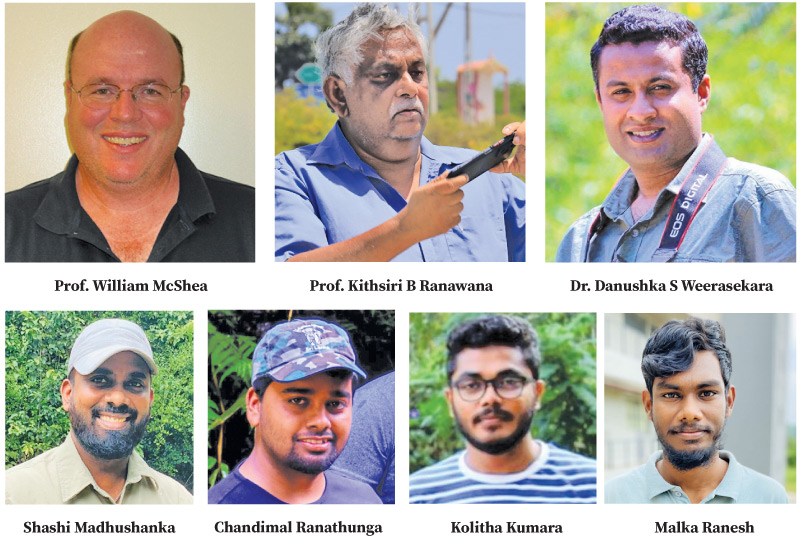

The HoDEC-lk Team comprises dedicated professionals and researchers committed to wildlife conservation. The team is led by Prof. William McShea, a Wildlife Ecologist and Project Supervisor from the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, with extensive expertise in forest mammal conservation and mitigating human-wildlife conflicts. Prof. Kithsiri Ranawana, a Senior Professor from the Faculty of Science, University of Peradeniya, and an Ecological Association of Sri Lanka (EASL) member, is also a Project Supervisor. Dr. Danushka S. Weerasekera, the Project Director, oversees the initiative under the EASL. Shashi Madhushanka, a Field Ecologist from EASL, and Chandimal Ranathunga, a Senior Lecturer at Sabaragamuwa University of Sri Lanka and a Field Ecologist HoDEC-lk project at EASL, support fieldwork. The team also includes dedicated Field Assistants, Kolitha Kumara and Malka Ranesh, who are passionate about wildlife conservation.

Prof. William McShea

Wildlife Ecologist & Project Supervisor

Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute

Prof. Kithsiri B Ranawana

Zoologist and Project Supervisor

Faculty of Science, University of Peradeniya Member, The Ecological Association of Sri Lanka (EASL).

Dr. Danushka S Weerasekera

Project Director, HoDEC-lk

Shashi Madushanka

Field Ecologist & Naturalist, HoDEC-lk

Chandimal Ranathunga

Senior Lecturer, Sabaragamuwa University of Sri Lanka

Field Ecologist, HoDEC-lk

Kolitha Kumara

Field Assistant, HoDEC-lk

Malka Ranesh

Field Assistant, HoDEC-lk

Collaborating Institutions

Ecological Association of Sri Lanka

Correspondence:

[email protected]

[email protected]