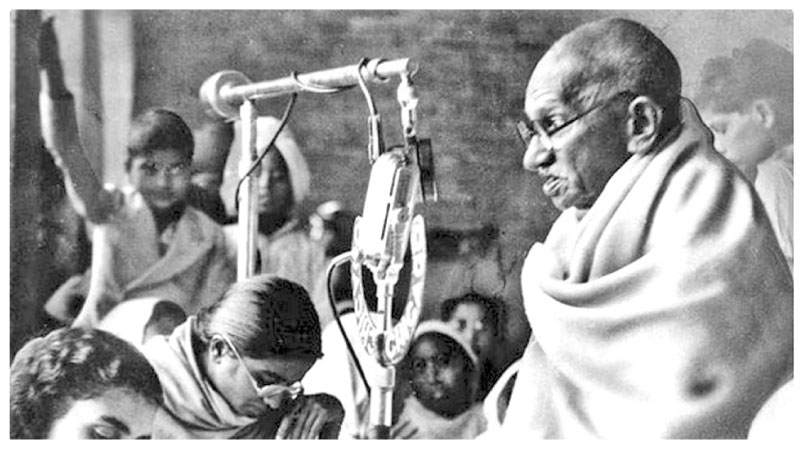

January 13 is the 77th anniversary of Gandhi’s last fast which was aimed at restoring Hindu-Muslim amity in riot-torn Mehrauli near Delhi

Mahatma Gandhi, the icon of the Indian freedom struggle, pioneered the use of “fasting” to goad his British and Indian adversaries to view thorny issues from the larger and deeper moral, social and humanitarian angle. His intention was to ensure that the social fabric or the body politic of India was not torn asunder by such conflicts and the larger good was served.

Gandhi went on major fasts 15 times between 1913 and 1948. The first was in South Africa, where he pioneered a new brand of “moralistic politics” that he practised in his subsequent struggle for India’s independence. The last fast, from January 13 to 18, 1948, was to stop Hindu-Muslim rioting in Mehrauli near Delhi, days before he was assassinated by a Hindu fanatic.

The gunman, Nathuram Vinayak Godse, editor of a Marathi journal Hindu Rastra accused him of pandering to the Muslims even after they had secured Pakistan by splitting India. Godse pumped three bullets into Gandhi’s chest with his Beretta revolver at a prayer meeting in New Delhi on January 30, 1948.

Communal carnage

Ironically, Gandhi was a staunch opponent of the vivisection of India on religious grounds, declaring that, “Partition of India will take place over my dead body.” And yet, he firmly believed that, having agreed to partition, India had no moral right to deny Pakistan its legitimate share of united India’s financial assets, which was INR 55 crores. He also wanted the communal carnage that marked partition to stop to let India survive.

Gandhi had also been even-handed in his campaign against communal violence. He did a “padayatra” through Noakhali in East Pakistan where Muslims were killing Hindus. He went on a “fast unto death” to stop the killing of Muslims by Hindus in Mehrauli near Delhi.

Gandhi had asked Pakistan’s rulers to ensure the safety of minorities and predicted that Pakistan would be an impermanent entity unless it evolved a secular polity, recalls historian Dilip Simeon of Ashoka University. Gandhi warned those who were pained by partition, that “Akhand Bharat” or United India could only be established by love and mutual respect, never by force.

But all these fell on deaf ears. Godse and other Hindu hotheads branded him as “the Hindus’ enemy number one”. His prayer meetings in Delhi were interrupted by anti-Gandhi sloganeering. Objections were raised to reading passages from the Quran in addition to the Gita.

Gandhi broke his seven-day fast on violence in Mehrauli on January 18, 1948, only after political leaders of the day fulfilled his conditions which were:

1) The annual fair at the Khwaja Bakhtiyar Islamic shrine at Mehrauli should take place peacefully. The festival is a celebration of communal harmony and cultural unity. It includes a procession of flower sellers carrying large floral fans, or pankhas, from the dargah of Khwaja Bakhtiyar Kaki to the Yogmaya Temple. The flower sellers pray for a better flower season by offering the pankhas to both shrines.

2) Over hundred mosques in Delhi converted into homes and Hindu temples should be restored;

3) Muslims should be allowed to move freely around Old Delhi;

4) Non-Muslims should not object to Delhi Muslims returning to their homes from Pakistan;

5) Muslims should be allowed to travel without danger;

6) There should be no economic boycott of Muslims.

During the fast, streams of ordinary folk and top political leaders visited him and he had discussions with them. Even Pakistan High Commissioner Zahid Hussain came calling. “Please lift the fast” Hussain pleaded, adding: “I’m getting calls every day from Pakistan asking about your health,” recalled Dilip Simeon.

Peace and amity

The fast did restore peace and amity in Mehrauli, but Hindu-Muslim animosity continued to simmer, breaking into violence periodically in one part of North India or the other.

The one-man Jivan Lal Kapur Commission which inquired into the assassination of Gandhi had concluded that the conspiracy to kill Gandhi involved V. D. Savarkar, the present-day icon of Hindutva. But sadly, a few years down the line, a Hindu nationalist Government installed Savarkar’s portrait in the Central Hall of Parliament. Commenting on this, Dilip Simeon, said, “It’s almost as if we, as a country, are celebrating the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. The consequences of the partition of India are still with us.”

For Gandhi, fasting did not involve just physical suffering. It involved “mental cleansing”. If fasting did not involve mental cleansing, it would be hypocrisy and end in ignominy, he said. Non-violence was not a sign of weakness nor was it motivated by political gain, Gandhi said. He saw non-violence, fasting and self-flagellation as a means of educating the adversary and appealing to his conscience through an act of self-sacrifice and self-infliction of pain.

In Gandhi’s eyes, the sufferings of the Satyagrahis would effectively demonstrate the “righteousness” of their cause, help change public opinion and inspire others to change themselves.

Commentators said that Gandhi drew a distinction between political hunger strikes and the doctrine of “Satyagraha”. Although he acknowledged the legitimacy of the former, he felt that the attitude of those engaged in hunger strikes had a streak of violence, was accompanied by rancour and hostility towards the adversary, an aspect totally absent in his “Satyagraha”.

Gandhi’s fasts had mixed results. The 1942 Quit India Movement, which aimed at securing independence from British rule immediately, was a significant moment in the Indian freedom struggle, and the fast undertaken by Gandhi in its support played a pivotal role in mobilising the public.

Thousands, including Gandhi, were arrested. Gandhi began a fast on February 10, 1943 to protest against the arrests. The British soon took into account Gandhi’s deteriorating health and the growing unrest, and on February 18, 1943, began talks with him.

Through his fasts, Gandhi sought to transform what might have appeared as a political struggle into a righteous and ethical struggle. Gandhi was the first to make fasting both a spiritual and political weapon.

The British rulers attempted to downplay the significance of his fasts and occasionally responded with repressive measures, but they did conclude that fasts were a potent form of resistance.

Gandhi fasted for a variety of causes. It was a penance for the immoral behaviour of his Ashram inmates in South Africa in 1913; against violent protests of radical factions of the independence movement in Bihar; to show solidarity with the ‘untouchables’ (Dalits); in opposition to the British proposal for separate electorates for the untouchables which he felt was socially divisive; and against Hindu-Muslim riots. The duration of these fasts varied from three-four days to 21 days.

A lasting weapon

In independent India, the fast, and even “fast-unto-death”, has been used to get demands met. The first major fast-unto-death in Independent India was in 1952 when Potti Sriramulu stopped eating, demanding a separate state of Andhra Pradesh for the Telugus of Madras Presidency. His death after 58 days of fasting sparked violent protests and finally led to the creation of Andhra Pradesh in 1953.

In 1969, Sikh leader Darshan Singh Pheruman fasted unto death over the demand to include all Punjabi-speaking regions, including Chandigarh, in the then newly-created Punjab State. Pheruman died after fasting for 74 days. His demands were met partially.

In November 2000, after 10 Manipuri civilians were gunned down by the 8th Assam Rifles, 28-year-old Manipuri activist Irom Sharmila began an indefinite fast against the killing, and also against the draconian Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA). Three days after she began her fast, Irom Sharmila was arrested for “attempting suicide” and remained in police custody for 16 years, where the authorities force-fed her through the nose even as she continued her hunger strike. The “Iron Lady of Manipur” ended her fast in 2016, but without achieving her goal.

There have been many fasts for a variety of causes. Medha Patkar’s on the Narmada waters and Anna Hazare’s to end corruption, got international attention. Fasts are regularly used by Indian political and social leaders agitating for various causes, though not always with success.