A human-made system is a collection of interconnected elements that work together based on a set of rules to form a cohesive whole. Shaped and influenced by its environment, a system is defined by its boundaries, structure and purpose, which are reflected in its operations. The establishment of a boundary involves determining which entities are considered part of the system and which belong to the external environment.

Systems are the focus of study in Systems Theory and other related disciplines. They share several common properties and characteristics, such as structure, function, behaviour and inter-connectivity. Systems Theory sees the world as a complex network of interconnected components.

Most systems are open, meaning they exchange both inputs and outputs with their surroundings. In contrast, a closed system only exchanges outputs with its environment, while an isolated system does not exchange anything with its environment.

An open system converts inputs into outputs, where inputs are utilised and outputs are generated. In the context of education, for instance, the output is the total number of students who achieve academic success by the end of their schooling, regarded as the final product of educational inputs.

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of what constitutes a system, the essential components it should include, factors that contribute to system failure and a conceptual framework of strategies to build system resilience.

A system

A system is a set of interconnected components that work together to achieve a shared objective. It receives inputs from stakeholders and other systems, which undergo specific processes to generate outputs. These outputs, when combined, help fulfill the system’s overall goal. It means that if a part or certain parts of a system fails to deliver, then the goals set to be achieved will obviously become a tough challenge. A World Bank report highlights that while Sri Lanka has achieved high literacy rates, it has struggled to deliver high-quality educational services (World Bank, 2013), particularly in science and mathematics and the lack of internet access in schools exemplifies how the interconnected elements of a system must align to successfully achieve its broader objectives.

A system can vary in complexity, ranging from simple to complex. A complex system, such as a social system, consists of multiple subsystems. For example, an educational institution is a social system made up of several subsystems, organised in a hierarchical structure and working together to achieve the institution’s overall goal. The design of school architecture can greatly affect students’ learning experiences, while the surrounding neighbourhood communities can also have a significant impact on schools. However, each subsystem has its own limitations and involves various inputs, processes, outputs, and outcomes, all aimed at achieving the system’s overall goal. Complex systems typically interact with their surroundings, making them open systems.

For a system to succeed, consistent feedback between its components is essential for achieving its goals. When any part of the system encounters an issue, the monitoring process must promptly signal the problem, allowing for necessary adjustments to stay on track with its objectives. This ongoing feedback loop is what gives the system its resilience. Feedback loops are systems and methods where the parties exchange information and learn from each other.

A system failure occurs when a system is unable to perform its intended function or experiences a significant disruption. It can happen in a number of ways for a number of reasons:

Providing comprehensive training to all stakeholders, from top-level decision-makers to grassroots participants, is essential to ensure seamless functioning of a system. Such training equips individuals with a clear understanding of their roles and responsibilities, contributing to the successful operation of the system.

Effective communication is another critical factor to ensure a system’s sustainability. Overlooking analytics and disregarding failure as a form of communication can result in severe consequences, potentially leading to system failure.

Integration with related systems is crucial for a system to effectively address ongoing challenges and future disruptions. Systems that cannot coordinate and integrate plans internally and across different levels are often compared to a body without a head. In such systems, decisions made at executive level are passed down to front-line workers as implementation suffers due to gaps at various levels.

A system should adopt a metrics-driven approach, leveraging analytics from other systems. By analysing data on productivity of various business departments, systems can identify areas of overall improvement and pinpoint opportunities for further enhancement.

Supporting employees is essential for a system to achieve objectives. They need to feel that an established procedure is in place to provide assistance when needed. Human resources play a critical role in the successful operation of any system.

Establish standards to ensure high quality in every aspect of a system, from the outset and throughout its operation. A mechanism should be in place to monitor and uphold these standards.

Recognise and reward employees for meeting deadlines and maintaining established quality standards. This not only motivates employees but also fosters an environment that supports long-term success of a system.

System resilience

System resilience refers to the system to endure significant disruptions, whether caused by human activities, natural disasters, or events such as a pandemic. It should maintain functionality and recover swiftly, with minimal or no impact on its capacity to provide the expected service. In essence, the system acts as a buffer, able to withstand obstacles and continue delivering its services with little to no major interruptions. A resilient system can adapt to changes in the environment through various means: risk management, contingency, and continuity planning.

It has been found in various reports of international organisations such as the World Bank that education literature efforts to cultivate more resilient education systems have been proposed to ensure better response and recovery to crises and increased preparation for new shocks and disruptions. However, without careful planning and understanding, these preparations will become claptrap. For instance, during and aftermath of the Covid -19, steps had been taken to prevent system collapse and online learning was introduced. However, online learning experience is different from courses offered online in response to a crisis or disaster. It is doubtful, in the Sri Lankan context, whether schools and universities working to maintain instruction during the Covid-19 pandemic had understood those differences when evaluating this emergency remote teaching. In such cases, Education System Resilience (ESR) is just a buzzword.

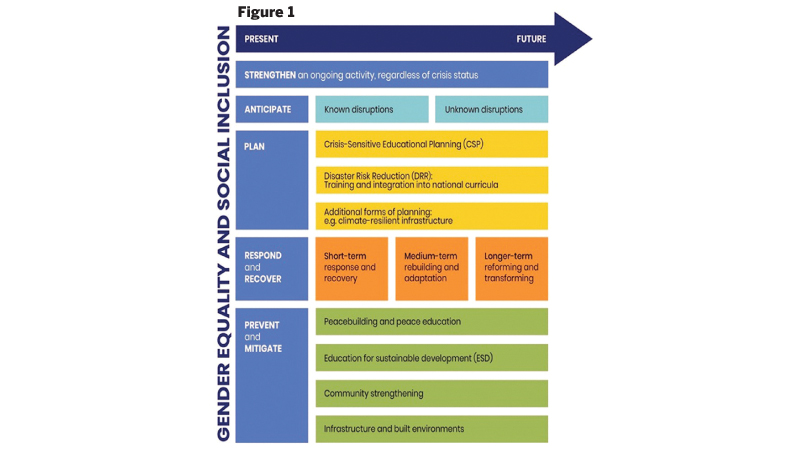

A conceptual framework should be the priority of policymakers and all stakeholders who will shape the curriculum and determine curricular and extra-curricular activities in the school environment. An ESR Framework should be characterised by policies and plans to embed overall system strengthening, to anticipate risk, to plan for and to respond and recover in times of crisis, and to prevent and mitigate future disruptions to a system. The framework should adapt to the needs according to various contexts.

The framework (see figure 1) to understand and examine education system resilience was developed as part of a scoping study commissioned by The Global Partnership for Education Knowledge and Innovation Exchange (GPE KIX). It was implemented by the Education Development Trust by incorporating academic and grey literature review, policy analysis and key informant interviews with education planning officials in low- and middle-income countries, all GPE partner countries.

One key aspect of system resilience, as shown in the framework, is anticipating known and unforeseen disruptions. This anticipation drives stakeholders to conduct risk analyses, examining past causes and potential future threats. Such proactive measures enable better preparation to safeguard the system, minimising or completely avoiding disruptions to routine operations.

Planning in risk management enables people to see potential risks and reduce their negative impact. Planning ahead is a continuous process like the resilient system itself.

The goal of planning is to help identify, assess, and prepare for potential risks that may arise along the way. It serves as a blueprint, guiding the system through every phase, from crisis-sensitive educational strategies to climate-resilient infrastructure development.

In the ESR framework, the ‘Respond and Recover’ phase plays a crucial role in translating planning into action during a crisis. This step is essential to guide managers in addressing disruptions promptly, minimising downtime, and subsequently rebuilding, reforming and transforming the system to ensure business continuity.

‘Prevent and Mitigate’ is a key aspect of system resilience, focusing on preventing future crises and reducing the impact of ongoing disasters. Policies and programs designed to minimize these impacts are vital elements of the system resilience framework.

The framework also focuses on gender equality and social inclusion since disaster situations often marginalise the victims according to various indexes such as gender, social status and geographical locations and many more and they are excluded from the recovery programs based on these indexes.

This framework primarily emphasises policies and planning rather than individual-level activities. It relies on a collective effort involving stakeholders at various levels, from policy-making to intervention and implementation. Therefore, the success of a resilient system hinges on adopting a top-down approach.

The definition of a system suggests that there can’t be a universal framework as a panacea to resilience. Therefore, the framework stated above can be a starting point and could be adapted to various contexts. Then, there is a system resilience in place anticipating events that can bring a halt to normalcy to any system.

In this line of argument, research communities should take the lead in refining the framework to their own context to ensure that policies and plans genuinely enhance resilience of a system, avoiding it from falling into a policy-speak and lamenting a system failure.

(The writer, is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of English Language Teaching, Eastern University, Sri Lanka.)