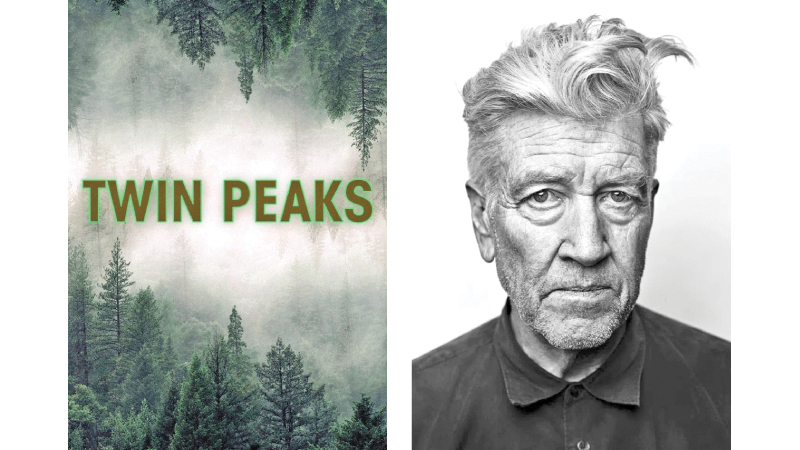

David Lynch died at the age of 78. By any measure the most influential filmmaker of our time, the Missoula, Montana-born artist left such a mark that his very name became an adjective. There’s Hitchcockian, and then there’s Lynchian.

Controversial, visionary, and absolutely singular, his films from “Eraserhead” and “Blue Velvet” to “Lost Highway” and “Mulholland Drive” were immersive plunges into rich cinematic landscapes of twisted psyches and luscious surfaces.

Born on January 20, 1946, Lynch’s life itself was one of unabashed Americana. As an Eagle Scout, he attended the inauguration of John F. Kennedy in 1961. From an early age, he was interested in painting, and becoming a professional artist was his sole preoccupation for much of his early life. Unhappy experiences at the Corcoran School of Fine Arts in Washington, D.C. and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, led to him travelling around Europe for three years with his friend and fellow artist, Jack Fisk, who would become the production designer on many of his films as well as a legendary collaborator of other filmmakers such as Terence Malick and Martin Scorsese.

Filmmaking

Eventually, Lynch settled in Philadelphia and enrolled in the Philadelphia Academy of the Fine Arts. Painting is something he’d continue throughout his entire career, but while in Philadelphia he experimented for the first time with filmmaking. Or rather, animation. His short “Six Men Getting Sick” from 1967 is a repeated animation showing symbolic vomiting. It’s eerie and unsettling, exactly what you’d think he might have made as his first film.

“It’s a beautiful day with golden sunshine and blue skies all the way.”

A particular combination of the cutesy and the absolutely disgusting would become a Lynch signature. Industrial imagery yet again pervades “The Elephant Man,” set in hazy, smokestack-filled 19th century London. Where “Eraserhead” was provocative, earning raves from the likes of Rosenbaum but condemnation from mainstream critics such as Roger Ebert, “The Elephant Man” was surprising for just how extraordinarily, overwhelmingly moving it was.

Lynch could combine genuine, heartrending emotion with unsettling material in a way no one else could touch. It’s what you feel when you hear Laura Dern’s Sandy in “Blue Velvet” relate her dream about a flight of robins spreading love over all the world. Or Major Briggs in “Twin Peaks” sharing his vision about his son, all scored to transcendent Angelo Badalamenti synths.

It’s what made Lynch’s first and only foray into blockbuster filmmaking such a misguided idea, when he accepted an offer from Dino de Laurentiis to direct an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s “Dune” in Mexico City after “The Elephant Man” earned an Oscar nomination for Best Picture at the 1981 Academy Awards. Lynch had previously said he met George Lucas about directing “Return of the Jedi,” a movie he had “next door to zero interest” in directing, and that he developed a massive headache when meeting with him.

With “Dune,” he did have a chance to give some of his signature flourishes. With Kenneth McMillan’s Baron Harkonnen, he was able to engage in a level of grotesquerie that was Lynch’s own. He fused outlandish sexuality with utter sadism in the spectre of Sting’s loincloth-clad Feyd Rautha in a manner that would pop up in his subsequent work. De Laurentiis took final cut out of his hands and ultimately delivered a more pedestrian vision for the theatrical cut in 1984. It bombed. In interviews throughout the rest of his life, Lynch made clear he disowned “Dune” and that the film was a great source of sadness for him.

Without “Dune,” we surely never would have gotten “Blue Velvet.” A re-teaming with Kyle MacLachlan, but also producer De Laurentiis, “Blue Velvet” represented a “one for me” after the “one for them” in his Herbert adaptation. For all the controversy it inspired, all the handwringing interviews asking him about its violence, its sexuality, and, even whether, as Roger Ebert alleged in his review of the film upon its release in 1986, it exploited its lead actress, Lynch’s then girlfriend Isabella Rossellini, this is a film made by an eagle scout from Missoula, Montana.

Movie history

“Blue Velvet” is one of those watershed moments in movie history. It was to 1986 what “Psycho” was to 1960. And with the particular combination of its extreme violence, sexual panic, and its homespun all-American aesthetic, was it actually a work of outsider art? Or a deeply conservative expression of Reaganism? The ’80s were a time when the ’50s did seem to make a comeback in many aspects of American life.

By the time he directed the pilot of “Twin Peaks” for ABC (he exerted a guiding hand over its first season and the early part of its second) the idea of what would be known as “Lynchian” was set. The extreme zoom out from the lattice-like ceiling of the police station when Ray Wise’s Leland Palmer is being interrogated in a Season 2 episode. Joan Chen’s Josie being trapped in a piece of furniture. An episode’s opening shot beginning in outer space. Anything was possible in the universe Lynch had created with “Twin Peaks.” You can draw a direct line from The Lady in the Radiator in “Eraserhead” to David Bowie’s voice giving life to a kind of industrial teapot in “Twin Peaks: The Return.”

Folksy and unsettling, homespun and avant-garde. You know Lynchian when you see it: It’s the teen angst of “Wild at Heart” and Willem Dafoe’s Bobby Peru graphically shooting his head off with a shotgun. It’s the headlights of a car frantically jostling down a lonely road like your eyes darting in REM sleep to start “Lost Highway.” It’s the digital hell of Robert Blake video-recording everybody in that movie, and the fuzzy bunnies and Phil Spector songs of “Inland Empire” (one of the early features shot on digital video). The campfires and muffled battle sounds on the soundtrack when war vets are recounting their past traumas in “The Straight Story” (a movie actually made for Walt Disney Studios and rated G, perhaps proving Rosenbaum’s thesis right). And it’s in the heart of his greatest film, the one that most profoundly captures his entire creative voice, “Mulholland Drive.”

Initially a kind of spinoff of “Twin Peaks” and developed as a TV show for ABC centered on the character of Audrey, “Mulholland Drive” ended up being rescued by French producer Alain Sarde when ABC rejected it (if ever there was a nemesis for Lynch, it was Bob Iger, who took creative control of “Twin Peaks” out of his hands and ultimately cancelled the show after it was a phenomenon in 1990.) The story of two women and their connection in the Hollywood Hills, “Mulholland Drive” captures the dreams, sweaty desperation, and down-on-one’s-luck depravity of Tinseltown better than any film since “Sunset Boulevard.”

No movie has shown the darkness of Hollywood quite like this, but also its lustrous beauty and possibility as summed up in two scenes: one where Naomi Watts’ Betty recites a bit of silly boilerplate soap opera dialogue, and another where she acts it out with the utmost passion and conviction and commitment as if it were Chekhov. There can be depth in shallow things. We call it Tinseltown, based on cheap Christmas ornamentation, but it sure does glitter, and it sure can be beautiful. With “Mulholland Drive” we got a film where many things can be true at once, where traumas and injustices exist but judgments aren’t quickly forthcoming; it’s hard to imagine how anyone could call this a Reagan-approved vision, even with an Old Hollywood star in Ann Miller appearing.

Nostalgia

Instead of relying on nostalgia, he delivered Kyle MacLachlan’s Dale Cooper as a barely sentient simpleton, among many other ways of breaking down and reframing the way viewers saw his creation. And like “Mulholland Drive” it mixed horror and deeply felt emotion in an unclassifiable way, turning “Twin Peaks” into a story about returning a somehow-revived Laura Palmer to her mother, who lost her murdered daughter so many decades before. Then, as anyone who was seen the show will remember, it ends with a scream. One still ringing in our ears over seven years later.

Lynch’s work had that ability to haunt. And his influence can be seen in so many places, there’s no point in even enumerating it. Yes, there’s Hitchcockian. And then there’s Lynchian. He was that magnitude of a talent. His vision was that potent. Both instantly identifiable and worthy of endless obsession and scrutiny and study. It will be a spectre that haunts cinema forever. – Indie Wire