Numerous anecdotes about Anagarika Dharmapala’s endeavours as a dedicated reformer remain largely hidden from the public. Despite several biographies written by various authors, much information regarding the notable events in Dharmapala’s life remains undiscovered.

Born into an affluent family in the late 19th century British Ceylon, Anagarika Dharmapala’s journey towards the Sinhalese Buddhist resurgence was deeply influenced by his associations with leading bhikkhus of the time. Beyond the well-known aspects of his life, a particularly interesting element is his audacity and the way the British viewed him as a potential threat to colonial governance, especially during the events of the Sinhalese-Muslim riots in 1915.

This tragic episode served as a wake-up call for the timid national leaders who were closely aligned with British colonial interests, marking a significant turning point in Sri Lanka’s history. Although Dharmapala was not directly involved in the events that led to the riots, the British naturally viewed him with suspicion due to his prominent role as an ideologue.

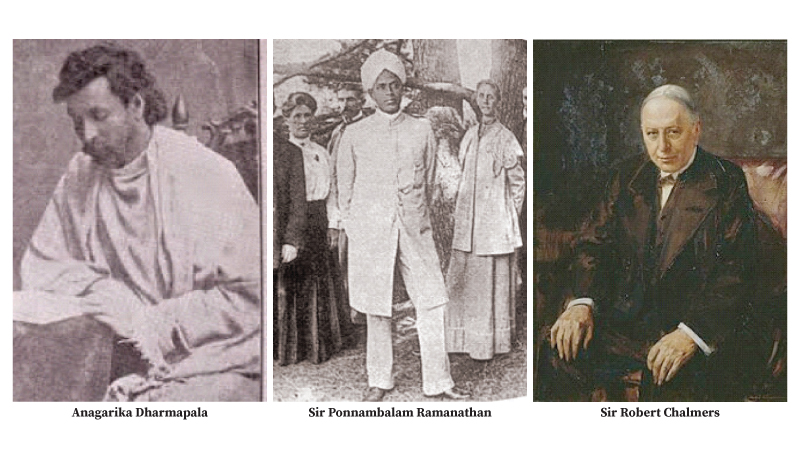

At the time the riots erupted, Dharmapala was in India, and his return to Ceylon was blocked when the Governor of Ceylon, Sir Robert Chalmers, requested that the colonial administration in Calcutta place Dharmapala under house arrest. Chalmers’ animosity towards Dharmapala stemmed from a previous incident when Dharmapala openly confronted him at the King’s House.

This confrontation occurred when Chalmers, curious to meet Dharmapala, arrived late to their scheduled meeting. Known for his punctuality, Dharmapala was outraged by the Governor’s behaviour and left the King’s House after making condescending remarks about Chalmers’ lethargy.

CID monitors Dharmapala

The British attempted to link the events of 1915 to an alleged nationalist resistance, coinciding with the 100th anniversary of the Kandyan Convention. Local supporters of the British made efforts to implicate Dharmapala in the riots, claiming that his ideology fuelled Sinhalese nationalism. Mudaliyar Reginald Fernando argued for Dharmapala’s arrest, asserting that his teachings incited ethnic clashes. He referenced the harsh language that Dharmapala used against the British, Christian missionaries, and local elites, expressing that he would not be surprised to see Dharmapala marching around the Queen’s House one day.

Officers of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), established in 1870, closely monitored Dharmapala’s activities even before the riots started in 1915. CID agents, disguised as civilians, frequently attended meetings organised by the Mahabodhi Society and the Sinhala Baudhaya, two significant movements initiated by Dharmapala, in search of evidence of his anti-colonial actions.

When Dharmapala was placed under house arrest in Calcutta, the CID searched the offices of the “Sinhala Baudhaya” newspaper under the supervision of IGP Dowbiggin, who was notorious for his actions during the 1915 riots. The press and its equipment were confiscated, leading to a dire situation for nationalist discourse. The CID maintained a special file documenting all of Dharmapala’s activities, while local British collaborators, such as Gate Mudaliyar Simon de Silva, translated Dharmapala’s articles in an effort to persuade the colonial secretary to arrest him.

Local elites

Admired by many today for writing the first Sinhalese fiction, Simon de Silva was a staunch colonialist who feared the sudden rise of Buddhist influence under Dharmapala. In his missive to the colonial secretary in 1916, he justified his plea to prolong Dharmapala’s house arrest by stating: “After quarrelling with Col. Olcott, Mr. Dharmapala abandoned the Theosophy movement and started Mahabodhi. Both Mahabodhi and its new publication, ‘Sinhala Baudhaya,’ are dangerous publications aimed at promoting ethnic choice.”

Based on recommendations from local chieftains, the colonial secretary continued the house arrest regulations against Dharmapala until 1920, overturning his right to return to his homeland despite the efforts of his well-wishers. The distinguished Tamil leader Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan wrote a petition to the Governor, insisting that Dharmapala should be allowed to return to Ceylon. Sir Ramanathan acted out of compassion, seeing the pitiable condition of Don Mallika Hewavitharana, Dharmapala’s mother, who lamented not seeing her son for years.

In his lengthy letter to the Governor, Ramanathan wrote to Sir John Anderson to allow Dharmapala to come back. He stated, “Unlike Gandhi, who inspires citizens towards civil disobedience, Dharmapala leads a hermetic life, living like a yogi and devoid of mundane concerns.

He even criticises the Buddhist clergy. Thus, Dharmapala will not pose a threat to the empire.”

Although the pleas from Ramanathan and Almond de Souza had a significant impact, the position of the colonial secretary remained adamant. He firmly considered Dharmapala to be a threat to imperial administration, and as a result, Dharmapala was not granted permission to return to Ceylon until 1920, which undermined many of his activities for the cause of national resurgence. Several reasons compelled local elites to persuade the Government to take a rigid stance against Dharmapala.

Primarily, the grievances developed among traditional loyalist families against him turned into animosity when he vehemently critiqued their lifestyle. Maha Mudaliyar Sir Solomon Dias frequently became a subject of Dharmapala’s contempt. In particular, when the McClum administration proposed to open taverns in every village, this decision received full support from local aristocrats such as Sir Christopher Obeyasekere, sparking Dharmapala’s ire towards the entire Mudaliyar clan.

Amid the threats that encircled him in a chaotic period that the island was facing, Dharmapala showed his accustomed fortitude. While engaging in many activities to promote Buddhism in Bengal, he attempted to convince the British rule in Ceylon that he was not a threat to the British empire. The letter he wrote to Sir Joh Anderson referred to his financial contribution to the imperial war effort in the Great War. But, the opinion inculcated by the local elites in the mind of the Governor shunned the expectations of Dharmapala to return to his country until 1920.

The writer is a lecturer at the Department of International Law, Faculty of Law, General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University