It was a brief remark made during a mundane session of Parliament. But to Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister, Dr. Harini Amarasuriya, it was the moment she realised that her country wrecked not long ago by strongman leaders and their populist politics, had entered a potentially transformative moment for women.

A male colleague (and “not a very feminist” one, as Dr. Amarasuriya described him) stood up to say that the island nation could not get more women into the formal workforce unless it officially recognised the “care economy” — work caring for others.

To Dr. Amarasuriya, it was “one of the biggest thrills” to hear language in Government that had long been confined to activists or to largely forgotten gender departments. “I was like, OK, all those years of fighting with you have paid off”, she said with a laugh during an interview in December at her office in Colombo, the capital.

Political dynasty

Two years after Sri Lankans rose up and cast out a political dynasty whose profligacy had brought economic ruin, the country is in the midst of a once-in-a-lifetime reinvention.

Anger has steadied into a quieter resolve for wholesale change. Through a pair of national elections last year, for President Anura Kumara Dissanayake and for Parliament, the old elite that had governed for decades was decimated. A Leftist movement has risen in its place, promising a more equal society.

As the country’s democracy rebounds, opportunities are opening for women.

Driving force

Women were a driving force behind the protest movement that forced Sri Lanka’s President to flee in July 2022. When the country all but ran out of cash and fuel, the burden fell disproportionately on women, who shoulder the domestic load. Their rage sent them onto the streets.

Now, women are at the centre of efforts to give the country lasting protections against the whims of strongmen. Women are also doing the slow and steady work of shaping a political culture that allows them equal space.

Women, who make up 56 percent of registered voters, were crucial to the electoral victories late last year by National People’s Power (NPP), a small Leftist outfit.

President Dissanayake, the party’s leader, has spent his life in Leftist politics. He appointed Dr. Amarasuriya, a sociologist and activist, as Prime Minister, the country’s second-most-powerful post. She is the first woman to hold such a high post in South Asia who was not the wife or daughter of a previous top leader.

In September, as she prepared to take office, Dr. Amarasuriya was nursing a cold when New York Times reporters visited her home, its walls covered in cat art. One of her four cats was giving her attitude, she said, faking a limp as she tried to feed her.

She was keeping an eye on the political debates in the United States, where she spent a year as an exchange student. “I guess I am one of those ‘childless cat ladies,’” she said with a smile, referring to a dismissive comment by now-US Vice President J.D. Vance that became a rallying cry for some American women.

Dr. Amarasuriya has long preached that a more equal society cannot be achieved without making governance more women-friendly, injecting what she calls “feminist sensitivity” into policymaking.

Mobilising women politically

The new Government is taking up policy debates on improving pay parity and making work environments better for women. It hopes to raise the rate of female participation in the formal work force to about 50 percent, up from 33 percent. The governing party is doubling down on its efforts to mobilise women politically to ensure that this moment is not fleeting.

It is “a change of the way you think about government, the way you think about power and authority,” Dr. Amarasuriya said.

Some of the earliest actions have included ending the VIP culture around politics. Gone are the long motorcades, large security details and lavish mansions for ministers. President Dissanayake has slashed his travelling entourage. The Prime Minister’s compound Temple Trees, which under its previous occupant buzzed with the activity of over 100 staff members, now has a library-like quiet, as Dr. Amarasuriya works with a staff of just a dozen.

Outside the lobby leading to her office, as well as on her desk, are framed drawings that schoolchildren have been sending her. One showed Dr. Amarasuriya in a blue sari and her natural curls.

“Prime Minister Auntie,” the writing on the drawing said. “May the Buddha bless you”

The true test will be the economy.

It is stabilising, bolstered by an uptick in tourism and reductions in Government expenditure after decades of runaway spending. But it is not out of the woods yet.

Kaveesha Maduwanthi, 18, who works at a clothing factory, is among the many who hope that the country’s new leaders can find a way to boost economic growth.

Ms. Maduwanthi earns about US$ 100 (approx. Rs.30,000) a month. Her husband, a mason, brings home roughly the same amount if he gets steady work.

She said that more than half of her salary went on baby formula for her daughter, who turned one in January.

On top of that, she and her husband pay for the food and medicine of grandparents who babysit the girl while they work.

“We don’t need the Government providing us with food — we can somehow manage,” she said. “What we need is a country where I have the space to make a little extra cash so I can invest in my daughter — maybe a pair of gold earrings for her first birthday.”

Before the Presidential Election last year, the NPP, the Leftist party, spent about two years trying to mobilise women of the likes of Maduwanthi. Women, Dr. Amarasuriya and other party leaders argued at the time, were looking for someone to champion the issues they felt strongly about.

After female voters helped lift President Dissanayake to victory in the Presidential vote, the party won an absolute majority in Parliament weeks later. In many Districts, women won handily.

Dr. Amarasuriya, running in Colombo, broke a record for votes that had been held by Mahinda Rajapaksa, a former Prime Minister, President and war hero and the older brother of Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the President who was ousted in 2022.

The ample victories by Dr. Amarasuriya and other women shattered a myth that female politicians could not win, she said. Her party raised money centrally and distributed it evenly to female and male candidates to overcome disadvantages that women face.

Women in Parliament doubled

The number of women in Parliament doubled. Still, the country has far to go — women still make up just 10 percent of lawmakers.

There are only two women among the 21 Ministers in Dissanayake’s Cabinet.

Dr. Amarasuriya and other female leaders said they were disappointed with those numbers. But the work of making the political culture gender-inclusive is not just about numbers, Dr. Amarasuriya said, but also a “constant process” to influence and sensitise policymaking and day-to-day governance.

The party says it is focused on entrenching its mobilisation of women to get more of them into leadership positions at lower levels of politics. The goal, it says, is to remove the pretext that there are not enough female leaders to be tapped for more prominent roles.

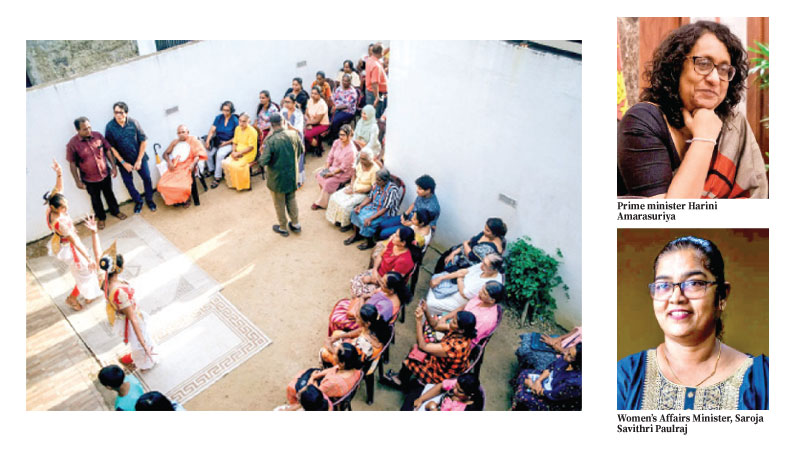

Across 13,000 of the 14,000 Grama Niladari Divisions, the smallest units of Sri Lanka’s local governance, the party has established women’s committees, according to the Women’s Affairs Minister, Saroja Savithri Paulraj.

On a Sunday afternoon in a suburb of Colombo, a new committee was being inaugurated. The organisers had canvassed door- to- door, collected information and created WhatsApp groups. About 100 people trickled in and sat in plastic chairs in the courtyard of a house.

Samanmalee Gunasinghe, the local Member of Parliament, took to the mic. “We used to be flower pots on the political stage,” Gunasinghe said. “They would take our votes and throw us into the fire afterward, abandoning us with our children.”

Now, she said, the women’s committees have created a space “where we can shout together.”

Mujib Mashal is the South Asia bureau chief for The Times, helping to lead coverage of India and the diverse region around it, including Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan. -New York Times