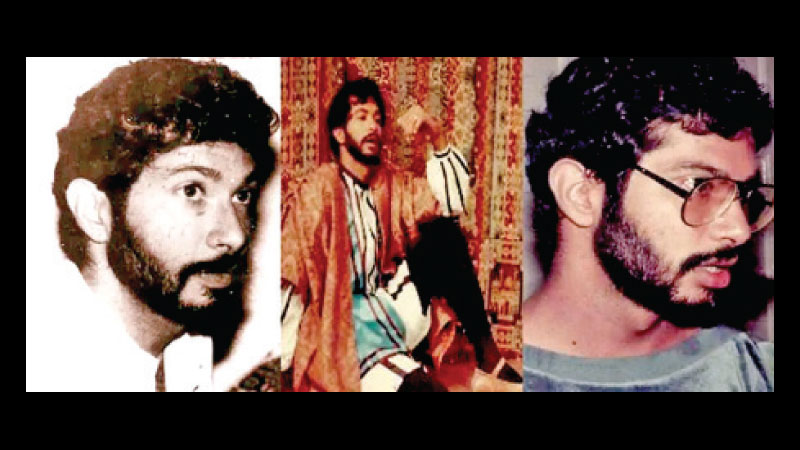

More than a month after its release, Ashoka Handagama’s Rani remains at the centre of public discourse. The film, which dramatises the events surrounding the tragic murder of journalist Richard De Soyza has ignited conversations that range from political interpretations of his death to broader discussions on the systemic violence and discrimination faced by Sri Lankan women.

More than a month after its release, Ashoka Handagama’s Rani remains at the centre of public discourse. The film, which dramatises the events surrounding the tragic murder of journalist Richard De Soyza has ignited conversations that range from political interpretations of his death to broader discussions on the systemic violence and discrimination faced by Sri Lankan women.

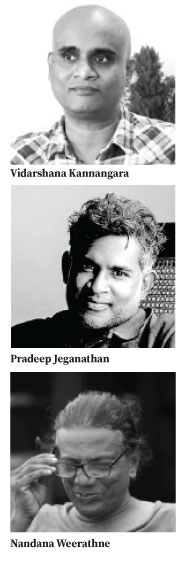

Adding to the ongoing debate, the ‘Yukthiye Kandawuma’ (Call of Justice) organisation hosted a panel discussion at the National Library on the anniversary of Richard’s abduction. The panel, which included Nandana Weerarathne, Pradeep Jeganadan, Widarshana Kannangara and Ashoka Abeyrathne, was moderated by Marine Nilashani. A fifth chair was left empty in honour of the slain journalist, symbolising both the absence of justice and the ongoing impact of his story.

Political context of Richard’s murder

Nandana Weerarathne, a writer known for documenting state violence, provided historical context, connecting Richard’s murder to a pattern of political assassinations.

He recounted the fate of Dharamaratnam Shivaram, one of the first to identify Richard’s body, who was himself found murdered in 2005. Weerarathne also highlighted the mysterious killing of dramatist and city councillor Lakshman Perera, speculating that his politically charged play may have made him a target.

Perera was abducted and killed just weeks before Richard’s murder, raising questions about connections between the two cases.

Perera was abducted and killed just weeks before Richard’s murder, raising questions about connections between the two cases.

Weerarathne explored the deep-rooted political dynamics that shaped the era, including the ascent of Ranasinghe Premadasa. He theorised that Premadasa’s rise from Colombo’s tenement gardens to the presidency was a calculated move by the UNP to groom a Sinhala-Buddhist leader, placing him in stark contrast with figures of the likes of Richard, whose lineage represented Colombo’s elite. The narrative of class struggle, caste disparity and political manoeuvering is crucial in understanding the tensions that culminated in Richard’s assassination.

A history of State violence

Anthropologist Pradeep Jeganadan placed state violence within a broader historical framework, citing Robert Knox’s 1681 account of King Rajasinghe II. He said that the State’s use of terror to subjugate its people is not merely a post-colonial phenomenon but has deep historical roots.

The mechanisms of control—arbitrary executions, public displays of brutality and silencing of dissent—have been ingrained in Sri Lankan governance across centuries. From the feudal monarchies to the British colonial administration and eventually the post-independence governments, the recurrence of state-sponsored terror reflects a persistent culture of impunity.

Jeganadan emphasised that while many perceive Richard De Soyza’s murder as an isolated event tied to the late 1980s, it is instead part of a continuum of state repression.

From the violence against Tamil civilians during the civil war to the suppression of leftist insurrections in the South, Sri Lanka’s history is marred by cycles of state brutality.

‘Film critic Vidarshana Kannangara addressed the portrayal of fear and complicity in ‘Rani’, noting its exploration of societal apathy. He referenced Slavoj Žižek’s analysis of cinema as a voyeuristic medium, likening the audience’s experience to Hitchcock’s ‘Psycho’, where viewers inadvertently empathise with the antagonist. Similarly, ‘Rani’ forces viewers to confront their own potential responses to state violence.

“There is a scene where Manorani rebukes her neighbours for not raising a hue and cry about Richard’s kidnapping, but earlier in the film, she acts just as apathetic about Richard’s friend being abducted,” Kannangara said. “This duality highlights how fear conditions people into silence and in doing so, enables oppression.”

Kannangara said that ‘Rani’ challenges viewers by denying them the explicit spectacle of Richard’s murder. “Audiences today are conditioned by commercial cinema to expect violent retribution or clear resolutions but Handagama subverts this by focusing on the emotional and psychological trauma that lingers long after an act of violence occurs.”

Role of cinema in remembering the past

Ashoka Abeyrathne emphasised the significance of ‘Rani’ in rekindling public memory about Richard’s murder. While Sri Lanka’s past is marred by the loss of approximately 60,000 young men in the South alone, ‘Rani’ serves as a reminder of the systematic suppression of dissent.

Abeyrathne also addressed audience criticism, particularly those who expected a graphic re-enactment of Richard’s murder.

He said that while filmmakers often face external pressures, internal artistic choices also shape the narrative, with directors sometimes choosing to imply rather than explicitly depict certain events.

“The biggest complaint we hear is that the film did not show Richard’s death in all its sordid detail. Some people wanted to see whether his body was dumped from a boat or a helicopter,” Abeyrathne said. “But cinema is not just about spectacle; it’s about evoking emotion and critical thought. The real power of ‘Rani’ lies in the questions it forces us to ask”, he said.

A decade of reckoning?

With ‘Rani’ sparking renewed discussions, the current decade appears to be one of reflection and reckoning. The film and its associated debates underscore an enduring question: How did Sri Lanka’s ‘Mafia State’ emerge, and what can be done to prevent history from repeating itself? As voices such as Richard’s continue to echo decades after their silencing, Sri Lanka finds itself at a crossroads between remembering and forgetting.

Moreover, the public response to ‘Rani’ highlights a generational shift in attitudes toward justice and accountability. For those who lived through the violence of the late ‘80s, the film serves as a painful reminder of unresolved crimes. For younger audiences, it offers an entry point into understanding a period of history that is often obscured or sanitised in official narratives.

As Sri Lanka grapples with contemporary challenges ‘Rani’ reminds us that the past is never truly ‘past’. The ghosts of state violence linger, demanding acknowledgment, accountability and ultimately, justice.