Her voice trembles as she recalls the pain that has defined her family’s existence. “For years, my parents fought tirelessly for his release, hoping that one day he would return home. But they both died waiting. After my father’s death, my mother’s grief turned into unbearable suffering. She lost herself in the weight of sorrow, tormented by the thought of my brother wasting away in prison. Now, I am the one left to fight for him.”

The struggle for justice for those victimised by the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) is far from over. The Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) is not just a law; it is a weapon of suppression that has been wielded for decades to silence dissent and imprison political opponents. Its victims have been Tamil political prisoners, activists, journalists and even ordinary citizens, many of whom have suffered detention without trial, torture and death in custody.

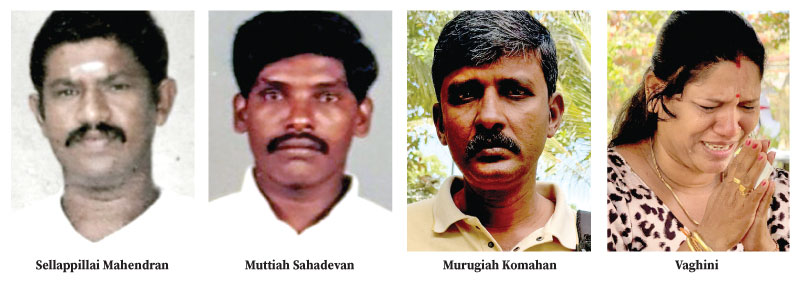

In Jaffna, the Sunday Observer met Murugiah Komahan, a former Tamil political prisoner who spent six years behind bars under this law. Today, he fights tirelessly for those still trapped in its grip. His story is not just his own, it represents the thousands of lives torn apart by this draconian legislation.

The article revisits two tragic cases of persons arrested under the PTA who died in custody. These stories stand as painful reminders of justice that came too late. However, also highlighted are two ongoing struggles where justice is still possible. In amplifying these voices, the question remains. Will history repeat itself, or will Sri Lanka finally break free from this cycle of injustice?

Sellappillai Mahendran

Sellappillai Mahendran, a toddy tapper from Batticaloa, was arrested in 1993 during a military search operation. He was accused of attempting to overthrow the Government and participating in LTTE attacks, charges based solely on a confession written in Sinhala, a language he did not understand. Mahendran had been a low-ranking LTTE member as a teenager but had left the organisation years before his arrest. Despite this, he was sentenced to life in prison plus 70 years, stripped of any possibility of freedom.

In the following decades, Mahendran fought relentlessly to prove his innocence, appealing his case in both the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court. But justice never came. He was never allowed to see the child his wife was pregnant with at the time of his arrest. After spending more than two decades in a cramped prison cell, Mahendran died at the age of 45, a victim of the cruel but existing system.

Muttiah Sahadevan

The public petition for the release of prisoners being handed over to the Presidential Secretariat

In 2005, Sri Lanka’s Foreign Minister, Lakshman Kadirgamar, was assassinated by an unknown sniper. In the aftermath, Muttiah Sahadevan, a daily wage labourer was arrested under suspicion of aiding the assassination. His alleged crime was cutting a tree branch near a house from which the fatal shots were believed to have been fired. It was a routine task he had done under the homeowner’s instructions.

Allegedly tortured into signing a confession he could not even read, Sahadevan spent 14 years in prison. His case rested solely on this forced confession under the PTA, while the actual owner of the house, a politically connected businessman was never questioned. Beaten until his teeth were broken, he told the court, “I was beaten for a crime I did not commit.” His family, too, suffered under the weight of injustice. His wife and children were interrogated and harassed, yet no evidence was ever found against him. Sahadevan remained behind bars until his health deteriorated. In 2019, he was transferred to the Colombo National Hospital, where he died from kidney failure. His death marked the end of a life stolen by a legal system that never gave him a fair trial. Following his passing, the Court closed his case for justice, which was denied until the end. The custodial deaths of Sahadevan and Sellappillai serve as grim reminders of the ongoing horrors faced by Tamil political prisoners.

Their fate echoes the fears of Murugiah Komahan, who endured six years behind bars, and Vigneshwara Nathan Parthiban, who has languished in prison for an unimaginable 30 years. In Jaffna, when we spoke to Vaghini, Parthiban’s sister, she confided her deepest fear that her brother might not leave prison alive. Having spent two-thirds of his life behind bars, Parthiban’s story is a chilling testament to the enduring brutality of the PTA. Her fear is not unfounded. Since 2009, at least 11 Tamil prisoners have died in custody, their names now part of a long and painful history of injustice.

Murugiah Komahan

Murugiah Komahan, a Tamil activist and former political prisoner, was detained under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) from 2010 to 2016. Reflecting on Sri Lanka’s history of detaining and releasing Tamil political prisoners, he said. “In 2009, after the armed conflict ended, approximately 12,000 people were rehabilitated and released during Mahinda Rajapaksa’s Government. Since then, many others arrested on suspicion of terrorism have faced trials, leading to either their release or continued imprisonment. Each successive Government has released a certain number of political prisoners upon coming to power. Yet, even today, 10 people are remaining in prison under the PTA.”

Sri Lankan prisons are notorious for overcrowding, poor sanitation, and inadequate medical care. Political prisoners under the PTA endure even harsher conditions, often denied basic healthcare. Komahan described this reality.

“PTA prisoners don’t receive the medical privileges of ordinary inmates. While others are referred to outside hospitals for serious conditions, we are confined to prison hospitals with inadequate care. Since 2009, 11 Tamil political prisoners have died in custody. Even in severe illnesses, we are locked in cells while others at least get hospital beds.”

Despite efforts and pledges by consecutive Governments, the release of Tamil political prisoners has been slow and inconsistent.

“We had high hopes for their release on Independence Day, but it didn’t happen. It was a major disappointment. Still, we wait and remain vigilant. Justice must be served,” he said.

A sister’s fight for justice

In Jaffna, we met Vaghini, a woman whose life has been shaped by an unending battle for her brother’s freedom. For over 30 years, her brother has remained behind bars, making him the longest-serving Tamil political prisoner in Sri Lanka.

“I was only 16 when he was taken from us. My mother told me that my brother was arrested in 1996 when we were in Vanni. He was just 18 then. Decades have passed, and yet he remains locked away. In all these years, he has only been allowed to leave his prison cell twice, once in 2017 when my father passed away and again in 2022 when my mother died,” she said.

“I was only 16 when he was taken from us. My mother told me that my brother was arrested in 1996 when we were in Vanni. He was just 18 then. Decades have passed, and yet he remains locked away. In all these years, he has only been allowed to leave his prison cell twice, once in 2017 when my father passed away and again in 2022 when my mother died,” she said.

Her voice trembles as she recalls the pain that has defined her family’s existence. “For years, my parents fought tirelessly for his release, hoping that one day he would return home.

But they both died waiting. After my father’s death, my mother’s grief turned into unbearable suffering. She lost herself in the weight of sorrow, tormented by the thought of my brother wasting away in prison. Now, I am the one left to fight for him.”

Through tears, she makes a desperate plea not just to the authorities but to the Sri Lankan people. “To those who are watching, to those who are listening, I beg you, understand our pain. My brother has been in prison for more than thirty years. Some might say, ‘If he is released, he will create problems.’ But the war ended long ago. So many have been freed. Why is my brother still in prison? All I ask is for him to be granted amnesty. Let him come home. Let him live with us. I don’t want anything else.” Her words are heavy with grief, but her determination is unwavering. After three decades of waiting, she refuses to give up.

Brutality of the PTA

Under the PTA, suspects can be detained without trial for prolonged periods, often based on forced confessions obtained through torture. Tamil political prisoners, activists, and journalists, alongside dissenters from all communities, have suffered under its unchecked power. Cases like Sellappillai Mahendran and Muttiah Sahadevan, who were detained, tortured, and denied justice, highlight its devastating consequences.

Despite repeated promises of reform, the PTA remains intact, undermining fundamental rights such as the presumption of innocence, legal defence, and protection from torture. Successive Governments have used it to silence opposition and control communities, particularly in the North and the East. Even after the civil war ended in 2009, the PTA’s reach expanded beyond Tamils to include Sinhala activists, poets, and Muslim writers. The 2022 Aragalaya protests further exposed its misuse, as authorities weaponised it against pro-democracy demonstrators, reinforcing its role as a tool of state suppression rather than justice.

A new pledge

At a public gathering in Vavuniya on November 11, 2024, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake pledged to release political prisoners upon the advice of the Attorney General. His manifesto was clear. If elected, he would dismantle draconian laws like the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) and end their misuse. However, arrests under the PTA persist until the Government takes steps to introduce an alternative, drawing criticism from various quarters. Recent cases include persons detained over an alleged security threat to Israeli tourists in Arugam Bay, accused of displaying LTTE-related symbols during Maaveerar Naal commemorations, Ganemulla Sanjeewa’s murder suspects, and three suspects who were involved in the Middeniya shooting incident.

Giving some hope to victims and all those concerned in January the Government announced it is in the process of preparing a Cabinet paper to establish a committee tasked with abolishing the PTA, Justice Minister Harshana Nanayakkara said.

At the time, he said the new committee would also focus on drafting a replacement piece of legislation, the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA), which aims to align fully with international human rights standards.

A crossroads for justice

The Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) was first introduced in 1979 with the stated purpose of preventing acts of terrorism and maintaining national security. Yet, over the decades, it has been weaponised against political opponents, activists, and ordinary citizens, turning into a tool of state repression rather than protection. Now, in 2025, Sri Lanka faces a new security crisis shaped by the rise of organised crime and underworld violence. Addressing Parliament during the February 28, 2025, Budget debate, President Dissanayake made a significant statement on the PTA.

“We are repealing the Prevention of Terrorism Act. No one has pushed for its repeal as much as we have. But we need a legal framework to combat organised crime and extremist threats. The PTA cannot be abolished until such a framework is in place,” he said.

While the Government’s stance is clear, the PTA’s dark legacy cannot be ignored. What was once enacted in the name of security became a tool of torture, indefinite detention, and human rights abuses. Sinhalese, Tamils, and Muslims alike have suffered under its unchecked power. Even now, 10 Tamil prisoners remain behind bars under this law, waiting for justice, while others never get the chance, dying in prison without proving their innocence.

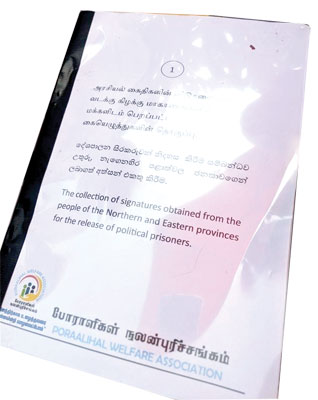

Last week a petition with 18,000 signatures was submitted to President Dissanayake by the Poraalihal Welfare Association, calling for the immediate release of Tamil political prisoners detained under the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA).

The large-scale petition saw thousands of persons, including families of detainees, activists, and concerned citizens join the call for the release of those imprisoned under a law that has long been condemned by human rights organisations.

The real question is whether history will repeat itself. If a new anti-terror law is introduced, will it truly protect the people or will it become yet another draconian tool of oppression? If the Government is sincere about reform, then this time, it must get it right. Any new Law must ensure accountability, prevent abuse and uphold human rights, or else, Sri Lanka risks stepping back into the same cycle of repression that has haunted it for over four decades.