Short poems have evolved across cultures, distilling profound emotions and ideas into concise forms. In ancient Japan, haiku emerged with poets like Matsuo Basho, who captured fleeting moments of nature, as in his famous verse:

“An old silent pond…

A frog jumps into the pond—

Splash! Silence again.”

In Persia, Rumi used brief yet powerful verses to express spiritual longing and love:

“The wound is the place

where the Light enters you.”

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam combined quatrains with deep philosophical reflections, such as:

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam combined quatrains with deep philosophical reflections, such as:

“The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.”

In modern times, Emily Dickinson revolutionized English poetry with her compact, enigmatic lines:

“Hope” is the thing with feathers—

That perches in the soul—

And sings the tune without the words—

And never stops—at all—

Meanwhile, Langston Hughes infused brevity with rhythm and social insight:

“What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?”

Short poems continue to evolve, proving that a few words can leave a lasting impact.Sri Lankan short poetry has evolved from classical Sandesha Kavya traditions to modern free verse, reflecting the nation’s shifting cultural and political landscape. In recent years, contemporary poets have embraced multilingual expression, blending Sinhala, Tamil, and English to address themes of identity, memory, and resistance.

In 2014, poets, Aryawansha Ranaweera and Nandana Weerasingha published a collection of short poems called තුන් පෙති හතර පස් පෙති (Thun Pethi Hathara Pas Pethi), that marked a turning point in the history of Sri Lankan poetry. The poems suggest fairness and inclusion, reminding us that prosperity and attention should reach all, not just the powerful. It subtly critiques inequality, advocating for shared light in society. The following poem from page 27 of their book explains the delicate reflection on equality in nature, capturing warmth and quiet grace in a few words.

Not just on the rock,

the sun also shines

on this blade of grass

පර්වතය මත විතරක්ද

මේ තණපත මතත්

හිරුඑළිය

To add to the value in the contemporary Sri Lanakan short poems Manjula Wediwardena published ‘Nimithi’, a collection of short poems most of which are shrunk into a handful of words but expressing eons of meanings in the readers’ imagination. Taking the whole idea of a short poem to create imagination by a visualised moment, Wediwardena hints highlights the deep, empathetic connection between human beings and nature, mostly reflecting an emotional resonance beyond words. Poem number six of his Nimithi is a great example.

Amazed, the horse’s eyes

find relief,

seeing the bright,

beautiful glow

in the baldhead’s gaze

කෙස්සබෑහිස

ලස්සන

අස්මතින්දිසි

රස්දෙස

විස්මයෙන්වුව

විස්මෘත

අස්වැසිල්ලක

අස්ඇස

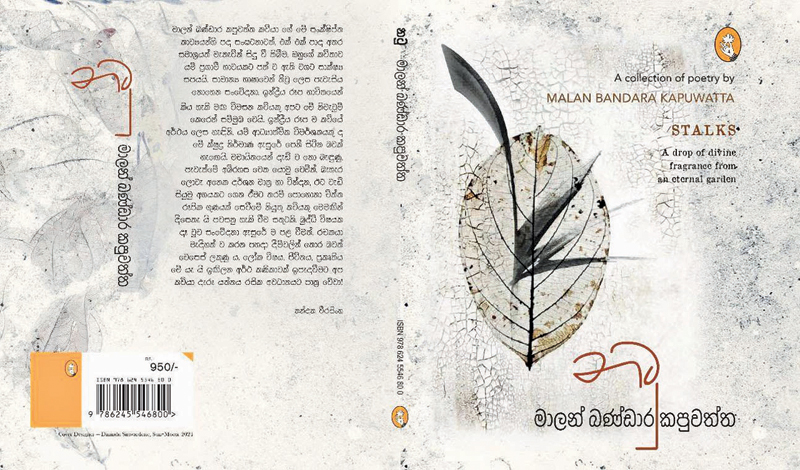

Malan Bandara Kapuwaththa’s recently published (Natu) takes a fresh approach, guiding readers along a journey where the present seamlessly connects with the past and extends into the future. While many of the poems draw from his personal experiences, the collection also weaves in vivid imaginative elements that highlight the persistent religion-based cultural and socio-economic conflicts in Sri Lanka.

Ancient altar

Priest secures

A loosened nail

On the cross

පැරැණි අල්තාරය

කුරුසියේ සෙලවෙන ඇණය

තදකරන පිය නම

(page 45)

This brief poem carries deep socio-economic and cultural significance. The priest fixing a loosened nail on the cross symbolises the struggle to uphold faith and tradition amid growing materialism. It reflects the financial challenges of religious institutions and the decline in church attendance, while also highlighting the resilience of spiritual heritage. Despite societal shifts, faith, like an old altar, endures, though it requires constant upkeep.

A similar idea is beautifully expressed on page 127.

The Souvenir Shop

Wooden Buddhas,

arranged in order

of height

සංචාරක අළෙවිසල

උසේ පිළිවෙලට වැඩ හිඳින

දැවමුවා බුදුවරු

This poem subtly reflects Sri Lanka’s socioeconomic realities, where tourism-driven commerce commodifies cultural and religious artifacts. The souvenir shop represents the country’s reliance on tourism, while the wooden Buddhas symbolise the tension between spirituality and capitalism. Their arrangement by height mirrors economic and social hierarchies, where wealth and power dictate status, much like Sri Lanka’s rigid class system. The poem also hints at the exploitation of artisans, whose craftsmanship is often undervalued in a market catering to foreign demand. Ultimately, it captures the paradox of a nation balancing cultural heritage with economic survival.

Malan writes about how strong a society can become when they get together to achieve a common goal.

I placed a log

across their way,

The marching ants

took a new path.

හරස් කොට තැබුවෙමි

මුගුරක්

නව මගක් ගෙන

කුහුඹු රැළ

(Page 59)

This poem symbolises resistance, adaptation, and collective resilience. The log represents obstacles like economic crises, corruption, or authoritarian rule, while the ants symbolise people uniting and adapting rather than surrendering. It highlights that revolutions do not stop momentum but redirect it towards justice and change. The poem’s open-ended nature raises the question: do the ants succeed, or do new barriers arise? This mirrors historical revolutions, where victories often lead to new challenges. Through minimalistic imagery, the poem captures political struggle and human perseverance, making it a powerful reflection on revolutionary movements.

The poet not only explores the universal socioeconomic and cultural divides across different societies but also delves into the emotions of loneliness, togetherness, emptiness, and fulfillment, carefully linking them to nature. Living overseas, Malan experiences firsthand how material luxuries cannot replace the presence of loved ones. He captures this indescribable feeling brilliantly in his short poems. Among many remarkable examples, this particular poem truly touched my heart.

Through Mother’s call

I hear a ting-ting,

a squirrel’s song

from my distant village

අම්මාගේ දුරකතන ඇමතුම

අතරින් ඇසෙයි

දුරු රට මාගෙ ගමේ

ලේනෙකුගේ ටිංටිං නද

(Page 139)

The poem evokes a deep sense of nostalgia and connection to home through sound. The “Mother’s call” symbolises warmth and belonging, while the “ting-ting” and the squirrel’s song represent distant yet familiar memories. The contrast between present and past highlights longing for one’s roots. Through simplicity, the poem beautifully captures the power of sound in rekindling emotions of home and childhood.

It is fitting to conclude this review with a remark by Manjula Wediwardena about this book. The title, Natu (Stalks), symbolises the fallen petals scattered on the ground, yet still intrinsically connected to their source. In the same way, Malan’s thoughts and themes remain rooted in the essence of his work, spreading across the 160 pages of his new book.

(Translated versions for the short poems in this article are by Dilini Eriyawala).