Part 01

March 14, 2025, will stand as a pivotal moment in Sri Lanka’s parliamentary history. The long-awaited Report on the Commission of Inquiry into the Establishment and Maintenance of Places of Unlawful Detention and Torture Chambers at the Batalanda Housing Scheme commonly known as the Batalanda Report, was finally tabled in Parliament, 27 years after it was handed over to then-President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga.

March 14, 2025, will stand as a pivotal moment in Sri Lanka’s parliamentary history. The long-awaited Report on the Commission of Inquiry into the Establishment and Maintenance of Places of Unlawful Detention and Torture Chambers at the Batalanda Housing Scheme commonly known as the Batalanda Report, was finally tabled in Parliament, 27 years after it was handed over to then-President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga.

The move came after former President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s somewhat disastrous interview with Al-Jazeera’s Mehdi Hasan which was telecast on March 6. The interview was marked by tense moments, with uncomfortable questions from Hasan and curt responses from the former Sri Lankan leader. However, none was more controversial than Hasan’s question about the Batalanda report. Wickremesinghe’s response, where he appeared to deny the validity of the report, sent shockwaves across the country. Many activists swiftly demanded that the Government table the report in Parliament, with some going as far as to call for immediate action. There were even calls to revoke Wickremesinghe’s civic rights, citing his alleged involvement in the events outlined in the report.

In response to the growing public outcry, the Cabinet, following extensive discussions, decided to table the long-suppressed Batalanda report in Parliament on Friday. Leader of the House, Bimal Rathnayake, presenting the report, underscored its historical significance and the alarming fact that, despite its gravity, the report had never been formally presented in Parliament since its completion decades ago.

Minister Bimal Rathnayake tabling the Commission Report in Parliamen

“As the main accused himself revealed during the Al Jazeera interview, it was never tabled in Parliament,” Rathnayake said, emphasizing the report’s long history of political obscurity. He said that the final Batalanda Commission report, along with relevant material, had been handed over to the Director of the National Archives on May 20, 1998.

Adding to the controversy, Rathnayake said that under the directives of then-President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, 750 printed copies of the report—including versions in Sinhala and Tamil had been produced. However, not a single copy had been forwarded to the Attorney General. “Those who called for this report not only failed to implement its recommendations but instead wielded it as a mere political tool during elections,” he said.

“It is evident that the report should have been handed over to then-President Kumaratunga before May 1998. However, the reasons for her failure to forward a copy to the Attorney General remained unclear until today, when they have become crystal clear,” Rathnayake said.

With mounting pressure for accountability, Minister Rathnayake said that the Cabinet, under President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has now resolved to seek the Attorney General’s advice on the Batalanda Commission Report, a move that could pave the way for long-awaited legal and political consequences. In addition to the decision to seek the Attorney General’s advice, President Dissanayake is set to appoint a committee to examine the next steps regarding the Batalanda Commission Report. The committee will be tasked with determining the appropriate course of action, considering the severity of the findings outlined in the report. In an effort to bring further transparency and accountability to the issue, a two-day debate will be held in Parliament.

****

Batalanda, about 15 km from Colombo, perhaps may be described as an unremarkable town, today and in the late 1980s. A nondescript housing complex, built for Government employees of the State Fertiliser Corporation at the time, it should have been just another quiet settlement on the outskirts of the country’s capital. But, for those who lived through the terror of the late 1980s, the name Batalanda even today is whispered with unease, a place where youth entered but never returned.

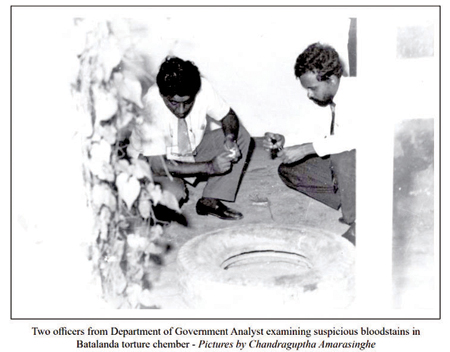

As the Batalanda Report stands as testimony, it is here where allegedly in the dimly lit rooms with cracked walls, terrors unimaginable took place as part of the State’s counter-offensive against Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) cadres. The brutal operation was one that swept up not just JVP youth but the innocent as well. Thousands disappeared and the lucky ones who survived carried with them stories too horrifying to believe until, years later, the Batalanda Commission sought to uncover the truth.

The Commission’s findings should have shaken the nation when it was finally published in 2000. It pointed fingers at those in power, including a future President. And yet, despite the gravity of its conclusions, no one was ever held accountable. But the report was neither tabled in Parliament nor forwarded to the Attorney General, its fate sealed by those in power at the time for reasons best known to them. But a condensed report was published as a Sessional Paper on February 9, 2000. Since then the only person who has consistently dared to speak out and accuse those he believes are responsible for the atrocities is investigative journalist Nandana Weeraratne, who has authored numerous books documenting the tortures that took place in Batalanda.

The Commission’s findings should have shaken the nation when it was finally published in 2000. It pointed fingers at those in power, including a future President. And yet, despite the gravity of its conclusions, no one was ever held accountable. But the report was neither tabled in Parliament nor forwarded to the Attorney General, its fate sealed by those in power at the time for reasons best known to them. But a condensed report was published as a Sessional Paper on February 9, 2000. Since then the only person who has consistently dared to speak out and accuse those he believes are responsible for the atrocities is investigative journalist Nandana Weeraratne, who has authored numerous books documenting the tortures that took place in Batalanda.

This series, Batalanda Files: Shadows of a Dark Era, will revisit that forgotten dark chapter of Sri Lanka’s history. Through extracts from the Commission report and expert analysis, the Sunday Observer, though many years late, will piece together the story of what allegedly happened inside Batalanda. Batalanda is not just about the past, it is a reminder of the present. Of how easily democracy can slip into dictatorship. Of how terror, when left unchecked, becomes part of a nation’s bloodstream.

Batalanda Housing Scheme

On the night of March 23, 1990, Earl Suggy Perera had found it difficult to sleep. “Sir, please kill me without hurting me anymore,” he had heard another person pleading with his captors in a nearby room earlier. A labourer at the Ministry of Health and a part time lottery ticket seller, Perera had been abducted by two unidentified men in the Kiribathgoda town earlier in the day. Brought blindfolded and trembling with fear, an unsettled Perera had no idea where he was. His only impression was that he had been brought to a house. He had heard the sounds of a television. His captors, he realised had finally led him to a room within the house. For several hours Perera was a silent witness to the beatings and the cries of other abducted youth. Now, unable to sleep, he had begged his captors to allow him to answer a call of nature.

With his blindfold and chains removed, Perera had been led to a toilet within the same building. Seizing the rare opportunity, he had cautiously peeked through a small window. From there, he observed that the building was located at the rear of a particular plot of land, its boundary fenced off with barbed wire. Beyond the fence, he saw several small houses in the distance.

Having been to the area before, Perera quickly realised that he was in the infamous Batalanda village. In fact, he later told the Commission that he had known for some time that adjacent to Batalanda was the housing scheme of the State Fertilizer Manufacturing Corporation, where people were being detained and tortured in some of the houses. The house he was housed in was later identified as B8. The house had been officially allocated from 1988 to 1991, to Security Officers assigned to ASP Douglas Peiris.

Assaulted and beaten for 22 days, including at the hands of the infamous ASP Douglas Peiris, Perera had witnessed others being beaten, hung upside down and left bleeding. His freedom was finally secured after his father had promised a payment of Rs. 50,000, which was later reduced to Rs. 10,000, to Attorney Lakshman Ranasinghe.

Allocation of houses

This housing scheme turned torture camp, had been in 1970, a part of a Sri Lankan Government’s ambitious project to manufacture essential fertiliser locally, with the goal of reducing the country’s dependency on imported fertiliser and lowering the cost of agricultural production. This initiative led to the establishment of the State Fertilizer Manufacturing Corporation, tasked with overseeing the production of various fertiliser, including urea. To achieve this goal, the Corporation set up a Urea Manufacturing Plant, with machinery procured from the United Kingdom’s Kellock Company, which was also responsible for assembling and maintaining the plant in Sri Lanka. A site in Sapugaskanda was selected for the plant and a special laboratory to facilitate work related to urea production.

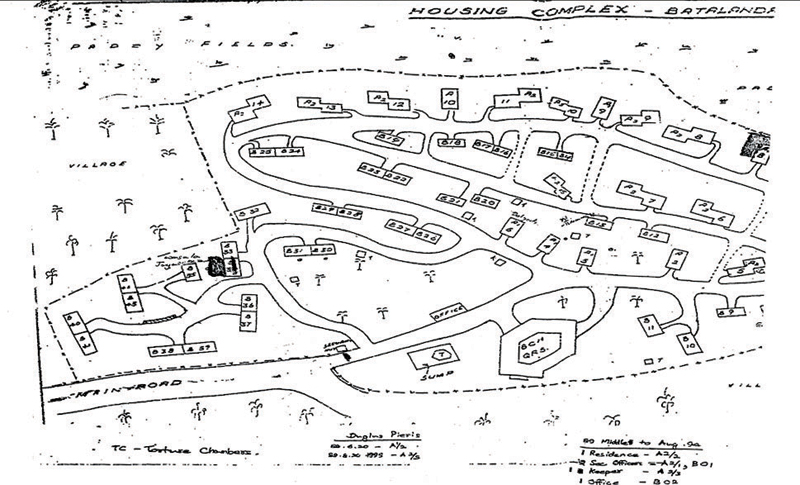

The map of the Batalanda Housing Scheme

Since foreign technical experts were expected to stay in Sri Lanka for an extended period, a housing scheme was designed for their accommodation. A coconut plantation, covering an area of several acres, was identified in Batalanda, a village in the Biyagama electorate within the Gampaha District, to build the housing units. The village, which was two-and-a-half kilometres from the State Fertilizer Manufacturing Corporation’s plant, would become home to foreign nationals working on the project.

By the early 1970s, the construction of the housing scheme was completed. The complex consisted of 64 housing units, designed to accommodate foreign experts and their families. The housing scheme featured a mix of units: 10 two-story type ‘A’ houses, 15 single-story type ‘B’ units with twin apartments, and 43 dormitory-style type ‘C’ units. The development was set within the heart of the Batalanda village, surrounded by coconut trees and was accessed via a single entrance from the Batalanda village road.

The housing scheme, which had originally been intended for foreign nationals, also included various amenities, such as an office complex, a clubhouse and a swimming pool. However, by the early 1980s, as the foreign technical experts completed their assignments and left Sri Lanka, the use of the housing units began to shift. With the departure of the foreigners, the State Fertilizer Manufacturing Corporation began allocating some of the housing units to its senior officers, while others were rented to the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) officials. By the mid-1980s, the Government further extended its control over the housing scheme when the Ministry of Defence requested the Corporation to release a portion of the land for military use.

As a result, an area on the left side of the housing complex was ceded to the Sri Lanka Army, which established a camp on the premises.

This new military presence marked the beginning of Batalanda’s transformation from a civilian housing area into a strategically significant, heavily-secured zone. Even after the formal allocation of houses to officers within and outside the Corporation, a few more houses were left vacant. As seen in the Commission report later, it is revealed through witness testimony that some of these vacant units were allocated for the use of then Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and his staff. The major issue brought to light in the Batalanda Comisson report revolves around the allocation of houses to the police for use as torture and detention centres during the 1980s. This revelation raises deep questions about the State’s involvement in such atrocities and the disturbing use of public resources for such nefarious purposes.

Next week’s article will provide an in-depth investigation into the allocation of these houses, shedding light on the dark history of Batalanda and its transformation from a housing scheme to a symbol of terror.