Part 02

November 1994 marked a significant political shift in Sri Lanka’s history. The election of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga as Sri Lanka’s 5th President ended the United National Party’s (UNP) 17-year rule, a period marked by violence, conflict and turmoil.

November 1994 marked a significant political shift in Sri Lanka’s history. The election of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga as Sri Lanka’s 5th President ended the United National Party’s (UNP) 17-year rule, a period marked by violence, conflict and turmoil.

Just two months later, the alternative newspaper Ravaya seized the newfound media freedom under Kumaratunga’s People’s Alliance (PA) Government to investigate disturbing reports of atrocities committed during the UNP’s rule.

Among the most haunting for journalist Nandana Weerarathne were the horrific accounts emerging from the Batalanda Housing Scheme, a rumoured state-sanctioned torture camp, located in the Biyagama electorate, just 13 km from Colombo. Encouraged by his editor, Victor Ivan, who saw the change in Government as an opportunity to “write reports to get the country on the right track through the People’s Alliance Government” , Weerarathne began documenting what he uncovered.

Influenced by Weerarathne’s reports, and possibly other factors, on September 21, 1995, Kumaratunga appointed a Commission of Inquiry under the powers vested in the Commissions of Inquiry Act to investigate the establishment and operation of unlawful detention centres and torture chambers at the Batalanda Housing Scheme.

The Batalanda Commission

Accordingly the Commission of Inquiry appointed by Kumaratunga, it was tasked with investigating and reporting on several key aspects related to the alleged atrocities at the Batalanda Housing Scheme. It was required to examine the circumstances surrounding the disappearance of Sub-Inspector of Police Rohitha Priyadarshana on or about February 20, 1990 and identify those responsible.

Similarly, the Commission was to investigate the circumstances relating to the arrest and detention of Sub-Inspector of Police Ajith Jayasinghe on or about February 24, 1990 and determine who was accountable. Furthermore, it was mandated to probe into the establishment and maintenance of unlawful detention centres at the Batalanda Housing Scheme, which was owned by the State Fertilizer Manufacturing Corporation, during the period from January 1, 1988, to December 31, 1990. The Commission was to ascertain whether persons detained at these locations had been subjected to cruel and inhuman treatment, including torture, and identify those responsible for such acts.

Similarly, the Commission was to investigate the circumstances relating to the arrest and detention of Sub-Inspector of Police Ajith Jayasinghe on or about February 24, 1990 and determine who was accountable. Furthermore, it was mandated to probe into the establishment and maintenance of unlawful detention centres at the Batalanda Housing Scheme, which was owned by the State Fertilizer Manufacturing Corporation, during the period from January 1, 1988, to December 31, 1990. The Commission was to ascertain whether persons detained at these locations had been subjected to cruel and inhuman treatment, including torture, and identify those responsible for such acts.

It was also required to determine whether any inquiries had previously been conducted into these incidents and whether any persons had directly or indirectly interfered with such investigations. The Commission was also empowered to assess whether any officers or other persons had committed criminal offences under existing laws, engaged in undue influence, or misused or abused their power in relation to these matters. Finally, the Warrant granted the Commission the authority to make recommendations based on its findings regarding the incidents under investigation.

Commission Members

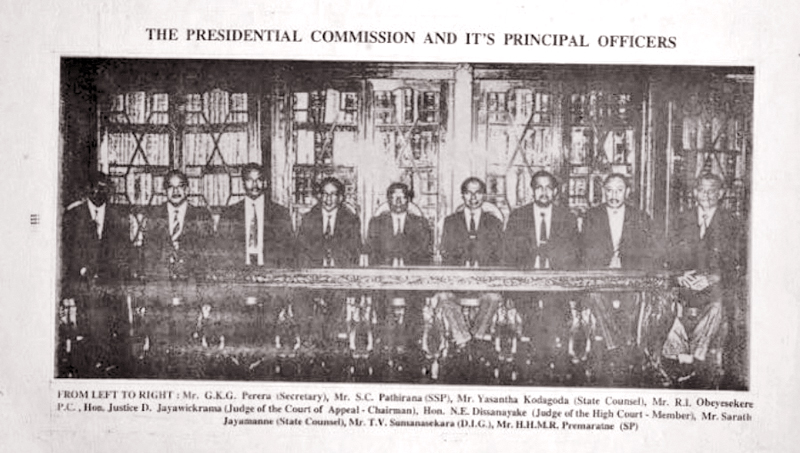

The Commission consisted of respected judges, capable administrative officers and police sleuths supported by other staff.

The late S. T. Gunawardena, a former Officer of the Sri Lanka Administrative Service and an Attorney-at-Law, was initially appointed as Secretary to the Commission at the time. However, he resigned on February 1, 1996 after a brief period in office. Following his resignation, the Assistant Secretary, David Geeganage, was appointed as Acting Secretary for a short time. On June 7, 1996, G. K. G. Perera, also an Officer of the Sri Lanka Administrative Service was appointed as Secretary of the Batalanda Commission.

R. I. Obeysekera PC, a former Crown Counsel at the Attorney General’s Department, also played a crucial role in assisting the Commission. As the President of the Committee of Human Rights of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka in 1996, Obeysekera brought significant expertise in human rights and criminal law. He had represented both the Crown and the Defence in numerous high-profile criminal trials, further strengthening his qualifications for this role.

In response to an invitation extended to former Attorney General Shibly Aziz, to nominate two State Counsel to assist the Commission at the time, State Counsels Sarath Jayamanne and Yasantha Kodagoda were also appointed. These two State Counsel were assigned critical responsibilities, with the endorsement of the then Attorney General Sarath N. Silva who had permitted them to continue assisting the Commission. Together with Obeysekera, these three Counsel had examined the witnesses.

Police investigators

Meanwhile two teams of police officers were assigned to assist the Commission in its investigative duties. One team was led by DIG T. V. Sumanasekera while the other was headed by SSP S. C. Pathirana. SP H. H. M. R. Premaratne also provided support to the investigators from the Criminal Investigations Department (CID), who were under the leadership of DIG T. Y. Sumanasekera.

The teams had already conducted preliminary investigations into certain aspects of the case before the Commission was appointed, and the material from those investigations was considered during the establishment of the Commission according to the report.

Once the Commission began its work, the investigative team continued to delve into these matters. The team under Pathirana, consisting of eleven officers permanently attached to the Commission, was tasked with investigating specific matters assigned by the Commission. Pathirana’s team worked closely with the Commission, reporting directly on their findings.

Balatanda Commission Members

As noted in the report, the wide publicity given to the proceedings of the Commission by both the print and electronic media played a significant role in encouraging public interest and participation. A large number of people attended the sittings of the Commission, with free and unimpeded access granted to the public. It is evident that the positive response from the public highlighted their strong desire to ascertain the truth behind the matters under inquiry.

As a result, the Commission said it received vital information, which greatly aided the investigation. Initially, the Commission was expected to submit its report by December 1995, but due to the high volume of information and evidence provided by witnesses, its tenure had to be extended 12 times. Extensions were granted to the Commission on various dates, starting from March 13, 1996 and continuing until the final extension, which required the Commission to submit the report by March 26, 1998. The unprecedented number of witnesses volunteering critical information necessitated comprehensive investigations, further justifying the need for these extensions.

The proceedings

The Commission held public sittings starting from January 16, 1996, continuing for 127 days. During these sittings, 82 persons appeared and gave evidence, and 126 items of productions and documents were submitted.

The proceedings of the Commission were conducted at the High Court of Colombo, in Court No. 2, a venue chosen to reduce costs associated with obtaining separate premises for the sittings. The Commission’s secretariat was based in Room No. 301A of the Superior Court Complex in Hulftsdorp, Colombo, with additional staff accommodation within the High Court Complex. Investigators, working under the leadership of SSP S. C. Pathirana, operated from an office at No. 18B, Summit Flats, Keppetipola Mawatha, Colombo 7.

Statements were recorded in these locations, and all proceedings were documented on audio tape, shorthand notes, and later transcribed into typed records. These proceedings, which span 6,780 pages across 28 volumes, were submitted alongside the report by the Commission to President Kumaratunga at the time.

Ranil Wickremesinghe giving evidence before

the Batalanda Commission

The Commission of Inquiry into the Batalanda Housing Scheme took extensive measures to ensure public participation throughout its proceedings. Notifications were published in Sinhala, Tamil, and English daily newspapers inviting the public to make representations on issues related to the terms of reference. These notifications encouraged members of the public to submit written statements, providing their names and addresses. Those who made such representations were initially questioned by police officers assisting the Commission. In cases where it was deemed that the persons could provide relevant and credible information on the atrocities, they were summoned as witnesses by the Commission. All decisions regarding the summoning of witnesses and the recording of statements were made by the Commissioners themselves.

Meanwhile, all witness testimony was recorded in open sittings, except for one instance where the Commission decided to record the evidence of a witness in camera due to the nature of their statement. This, as has been revealed today, was the statement of Reginald Sylvester Vincent Fernando, also known as Reggie, the caretaker of former President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s bungalow within the housing scheme at the time. Reggie died mysteriously a few days before Wickremesinghe was scheduled to appear before the Commission.

As per the Commissions of Inquiry Act, the Commission allowed witnesses to be represented by Attorneys-at-Law. During the process of recording evidence, it became clear that there was prima facie evidence suggesting that some persons had committed criminal offences, and some were involved in matters covered by the terms of reference. It is however important to note that due to the limited statutory powers of the Commission, they were unable to issue a notice to these persons, as would be the case under the provisions of the Special Presidential Commissions of Inquiry Act. Therefore, these persons were summoned as witnesses.

Over the course of the inquiry, three distinct categories of persons appeared before the Commission. Those who complained of criminal offences against themselves or people known to them, official witnesses who had no allegations against them, and persons alleged to have been directly or indirectly involved in criminal activities as outlined in the report.

During the proceedings, victims and witnesses shared harrowing accounts of the atrocities they had suffered, shedding light on the extent of the crimes committed in connection with the Batalanda Housing Scheme. Their testimonies revealed disturbing details about the perpetrators and the systemic issues that allowed such actions to take place. The Commission gathered valuable information from those directly affected by the incidents, as well as from officials and others involved.

During the proceedings, victims and witnesses shared harrowing accounts of the atrocities they had suffered, shedding light on the extent of the crimes committed in connection with the Batalanda Housing Scheme. Their testimonies revealed disturbing details about the perpetrators and the systemic issues that allowed such actions to take place. The Commission gathered valuable information from those directly affected by the incidents, as well as from officials and others involved.

Next week’s report will delve deeper into witness testimonies and key characters named in the atrocities of Batalanda, which has haunted a generation for decades.