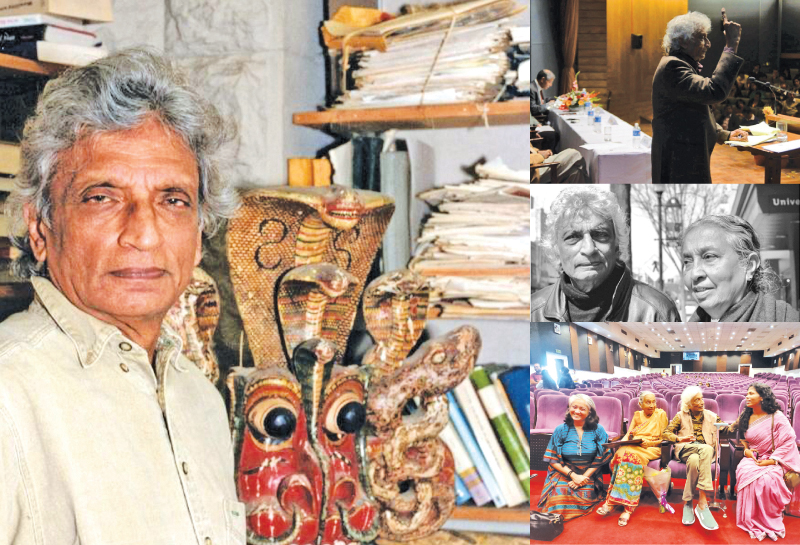

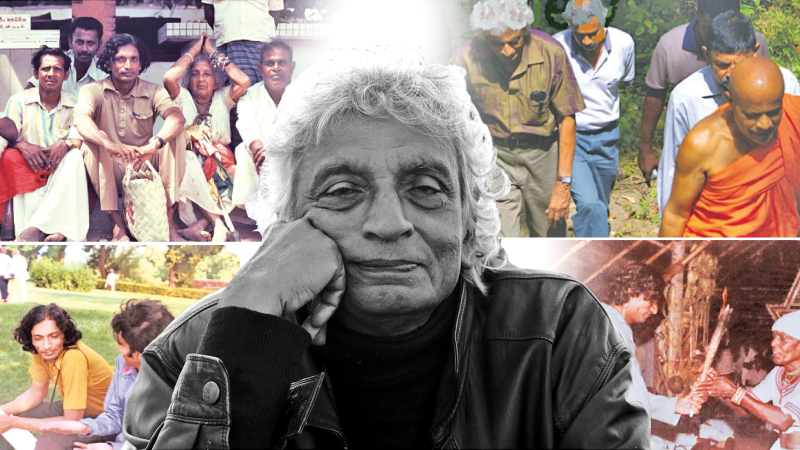

On March 25, 2025, the world lost one of its most original anthropological minds, Prof. Gananath Obeyesekere. Born in 1930 in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), Obeyesekere was not just an academic but a provocateur, a poet of ethnography and a relentless critic of colonial myths. His death marks the end of an era where Anthropology was not just about studying cultures but about engaging with them intellectually, emotionally and sometimes combatively.

Obeyesekere’s work spanned psychoanalysis, history, religion and literature, refusing to be confined by disciplinary boundaries. He wrote about Sri Lankan exorcisms with the same depth that he analysed Captain Cook’s apotheosis in Hawaii. He compared Buddhist meditators to Christian mystics, Freudian unconscious drives to Sinhala ritual symbolism, and colonial violence to nationalist myth making.

Obeyesekere’s work spanned psychoanalysis, history, religion and literature, refusing to be confined by disciplinary boundaries. He wrote about Sri Lankan exorcisms with the same depth that he analysed Captain Cook’s apotheosis in Hawaii. He compared Buddhist meditators to Christian mystics, Freudian unconscious drives to Sinhala ritual symbolism, and colonial violence to nationalist myth making.

This is the story of why his work matters not just to anthropologists but to anyone who cares about how cultures remember, how power distorts and how humans make meaning in an uncertain world.

From colonial Ceylon to global Anthropology

Gananath Obeyesekere was born into a world in flux. British Ceylon was still under colonial rule and the nationalist movements that would later shape Sri Lanka’s identity were gathering momentum. His early years in a village, followed by a move to Colombo exposed him to both traditional Sinhala culture and the imposed structures of colonial education.

At the University of Ceylon (now the University of Peradeniya), he studied English literature, immersing himself in Shakespeare, satire and the New Criticism movement. This literary foundation would later distinguish his anthropological writing – lyrical, ironic and unafraid of ambiguity.

But it was Anthropology that gave him a lens to examine his own society. After moving to the University of Washington for his PhD, he became part of a generation of non-Western scholars who began “studying back” turning the anthropological gaze onto the colonisers rather than just the colonised.

The Freudian turn: Psychoanalysis meets culture

Obeyesekere’s early work was deeply influenced by Freud but not uncritically. While many anthropologists dismissed psychoanalysis as ethnocentric, he saw its potential to understand how personal anxieties become collective myths.

Obeyesekere’s early work was deeply influenced by Freud but not uncritically. While many anthropologists dismissed psychoanalysis as ethnocentric, he saw its potential to understand how personal anxieties become collective myths.

His 1981 book, ‘Medusa’s Hair: An essay on personal symbols and religious experience’, began with a chance encounter,a woman in a Sri Lankan temple, her hair matted and wild, swaying in ecstatic devotion. To Obeyesekere, she was not just a religious figure but a Freudian puzzle: What unconscious forces drove such extreme acts of faith?

The book explored how individual trauma,sexual repression, castration anxiety, unresolved grief,transforms into public ritual. A man smashing coconuts on his head was not just performing a rite; he was externalising a psychic struggle. This was Obeyesekere’s great insight “culture does not just reflect psychology, it works on it, reshaping private pain into shared meaning.”

Work of culture and its discontents

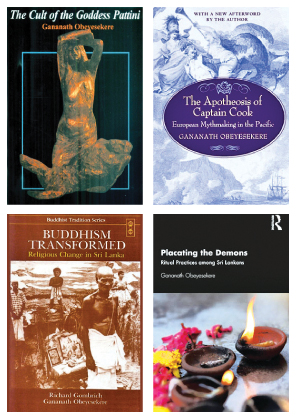

In ‘The Cult of the Goddess Pattini’ (1984), Obeyesekere documented a once-vibrant ritual tradition that was fading under modernity. Pattini, a deified heroine was worshipped through dance, drama and exorcism. But the book was more than Ethnography; it was a meditation on cultural loss.

“Pattini is a history of a past that is no longer present,” he wrote. The rituals he recorded in the 1950s had nearly vanished by the 1980s, victims of urbanisation and shifting religious attitudes. Yet, he said, these disappearing practices held keys to understanding Sri Lanka’s pre-colonial psycheits gender norms, its anxieties about disease and fertility, its resistance to Brahminical and European impositions.

Debating king Dutugämunu: When history becomes a weapon

One of Obeyesekere’s most politically charged interventions was his analysis of Sri Lanka’s ancient chronicles, particularly the Mahaavansa. The text recounts how the Sinhala king Dutugamunu defeated the Tamil ruler Elaara in the 2nd century BCE. In some versions, Dutugamunu is tormented by guilt over the slaughter; in others, he is a righteous hero and Elaara a villain.

Obeyesekere saw these contradictions not as historical “errors” but as debates frozen in time contentious dialogues that reflected changing political needs. When Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism surged in the 20th century, Elaara was demonised anew.

This argument enraged some scholars. Once, a bhikkhu, cut ties with Obeyesekere entirely, accusing him of undermining Sinhala pride. But for Obeyesekere, the lesson was clear: “History is never neutral. It is always contested, always alive”.

The Captain Cook controversy

In 1992, Obeyesekere dropped a bombshell ,“The Apotheosis of Captain Cook”. European historians had long claimed that Hawaiians mistook Cook for the god Lono, a narrative that painted Indigenous people as naive and Europeans as rational. Obeyesekere flipped the script.

The “apotheosis,” he said, was a “European myth”, not a Hawaiian one. Cook’s death was likely a political execution, not a case of mistaken divinity. The idea of ‘natives’ worshipping white men said more about colonial arrogance than Polynesian beliefs.

The Sahlins-Obeyesekere debate: A clash of paradigms

Marshall Sahlins, a towering figure in Anthropology, fiercely defended the traditional view. Their clash became one of the discipline’s most famous disputes. Sahlins the structuralist, insisting on cultural difference; Obeyesekere the humanist, insisting on indigenous agency.

Critics accused Obeyesekere of being “too literary,” of lacking fieldwork in Hawaii. But his point was broader. Anthropology had too often been complicit in colonial storytelling. The Cook debate was not just about 18th-century Hawaii, it was about who gets to write history, and why.

The late Masterpieces: Mysticism, madness and the limits of reason

In his final major work, ‘The Awakened Ones’(2012), Obeyesekere turned to mystics, Buddhist meditators, Christian saints and even the psychoanalyst Carl Jung. He asked: What happens when rational thought dissolves into ecstasy? Can Anthropology comprehend visions that defy empiricism?

The book was controversial. Some colleagues wondered why an Anthropologist was writing about Jacob Boehme’s pewter visions or Catherine of Siena’s trances. But Obeyesekere’s answer was simple, “If we ignore the irrational, we miss half of human experience”

The legacy of a restless mind

Obeyesekere knew his work was messy, contradictory, sometimes even wrong. But he embraced that. “One must be very humane to say, ‘I don’t know that,’” he once wrote, quoting Nietzsche.

His legacy is not a set of fixed theories but a “way of thinking”one that crosses borders, challenges dogma and finds poetry in the ethnographic. In an age of academic hyperspecialisation, he remained a generalist, a comparativist, a storyteller.

Obeyesekere’s challenge to Anthropology

Though primarily an Anthropologist, Obeyesekere was deeply sceptical of the discipline’s traditional authority to define “other” cultures. He said that ethnographies should be seen as “provisional frameworks”, not final truths. Every cultural account, he believed, is incomplete, shaped by the historian’s biases, the gaps in evidence and the fluidity of human memory.

This perspective was radical in a field that had long presented its findings as objective. For Obeyesekere, Anthropology was not about capturing a culture in amber but about engaging in an ongoing dialogue, one that acknowledges its own limitations.

The danger of speaking for others

His critique extended to the very act of writing about cultures outside one’s own. In ‘The Apotheosis of Captain Cook’, he showed how European narratives had distorted Hawaiian perspectives. But his warning was broader, “Anthropology must constantly question its right to represent”. This was not a call to abandon cross-cultural study but to approach it with humility. Ethnography, he said, should be a “collaborative process”, where the “observed” have as much voice as the observer.

Towards a more authentic Anthropology

Obeyesekere’s vision was of a discipline that evolves,one that moves beyond colonial frameworks toward a more authentic, self-critical practice. He did not reject Anthropology but sought to redeem it,to make it a tool for mutual understanding rather than domination.

In this sense, his work was not just academic but ethical. It asked “How do we study others without silencing them? How do we write about cultures without freezing them in time?”

Why Obeyesekere still speaks to us?

As Sri Lanka continues to wrestle with the weight of post-war reconciliation, as Native Hawaiians reclaim silenced histories from the shadows of colonial memory and as Anthropologists the world over question whether their craft can ever be truly decolonised, Gananath Obeyesekere’s voice still lingers urgent, unsettling and deeply relevant.

He reminded us that “cultures are not static”. They breathe, break, remember and forget. They resist, evolve and speak back. The colonised are not mute subjects of study, but living agents of meaning and the scholar’s duty is not just to analyse, but to listen, to feel and to question their own place in the story.

Obeyesekere believed that Anthropology is “as much art as science” an endeavour that demands irony, empathy and yes, even a touch of foolishness. Ethnography, for him, was never a final word, but a beginning. A provisional, imperfect attempt to grasp the shifting kaleidoscope of human experience.

Now, the man who challenged us to see the world in all its complexity has departed “to the land of nothingness,”as he called it. His final words, whispered with clarity and peace, “Let me go. I am going to the land of nothingness.”And yet, his intellectual presence refuses absence. Obeyesekere still speaks. In the questions he raised. In the myths he unraveled. In the uncomfortable silences he taught us to hear.

In this age of contested truths and fractured narratives, his challenge remains to think deeply, to doubt wisely, to feel fiercely and above all, to recognise that the human world is never finished. It is always becoming.