The Sinhala and Tamil New Year is all about transition. Astrologically, the reason is the transit of the Sun from Pisces (Meena) to Aries (Mesha). Traditionally, it marks the season where farmers and others pay homage to the Sun for a bountiful harvest, which gives them new hope. In other words, a period of transition in their lives, a sort of renewal and transformation.

The roots of the traditional New Year go back thousands of years. In fact, Oriental cultures have based their calendars – and daily life – around the movements of the Sun and the Moon for millennia. The festival is a homage to the Sun, which gives us life. Our food is literally made by the Sun through the process of photosynthesis, which is really the basis of all life on Earth. Thus, the New Year traditions evolved as a result of farmers expressing their gratitude to the Sun and Nature for a bountiful harvest, paving the way for a transformation in their lives.

In fact, the very word “Sankranthi” (transition) derived from Sanskrit says it all. Variations on this theme can be found in virtually all Asian countries. For example, in Thailand the traditional New Year period is known as “Songkran”, derived from Sanskrit.

It is easy to see why the traditional New Year is thought of as a rejuvenation of one’s soul. Avurudu and Puthandu (in Tamil), as the Sinhala and Tamil New Year is often called in Sri Lanka, is an occasion to forget the past and forgive one’s adversaries. After all, life is too short to hold onto grudges. In coming to terms with the past and reconciling with any person or persons with whom you had some sort of disagreement, you become a new person. Life thus begins anew at Avurudu.

Significantly, the Sinhala word “Bak” for the month of April signifies “fortune”, being a derivative of the Sanskrit root word Bhagya, which also is a common name in many Asian countries.

Torrent of commercialism

No other annual event brings the country together like the Sinhala and Hindu New Year, which is celebrated every April. Although primarily celebrated by Sinhala Buddhists and Hindus, it has now become a national event that transcends all man-made boundaries.

Indeed, those belonging to other communities and religions participate in Avurudu events with great enthusiasm.

Indeed, those belonging to other communities and religions participate in Avurudu events with great enthusiasm.

But one question remains: Whether the excessive commercialisation of our national events including Avurudu, Vesak and Christmas is a healthy trend.

Take any newspaper and you will see hundreds of advertisements targeting the Avurudu season, for everything from electronics to clothes. The message of unity and happiness embedded in the Avurudu celebrations is in danger of being submerged in this torrent of commercialism.

It spares no one even the remotest areas and the most innocent of minds have been swamped in this mad rush. It is a tough battle tradition versus modernity that could leave the former battered and bruised.

Family time

Contrast today’s situation with that experienced by generations that knew nothing about commercialism. I still remember those pre-TV days when Avurudu was a merry occasion without even a hint of artificial gloss. In far-off villages, Avurudu was a unique celebration of life itself.

It brought the entire village together in a spirit of camaraderie, buoyed by an air of festivity. It marked a new beginning for the entire village, which was heavily dependent on agriculture.

All the families in the village strictly followed the traditions associated with Avurudu. It was a marvellous time for children – unlike today, there was no pressure from adults to study all day and no tuition classes to attend.

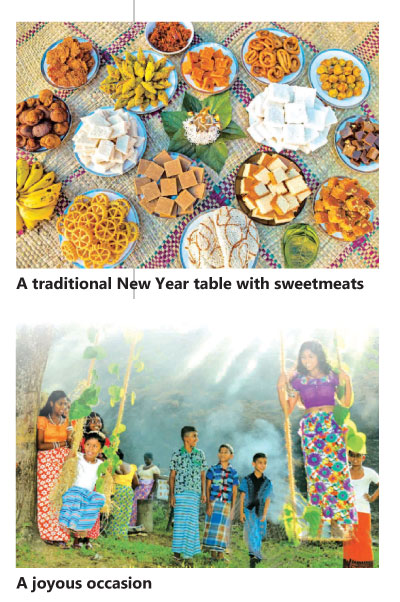

Today, you can walk into any supermarket or pastry outlet and buy sweetmeats (Rasakevili) to your heart’s content. This was not the case all those years ago. Sweetmeats had to be made at home, and in any case, no one would have it any other way. Children looked forward to this more than any other event associated with Avurudu. After all, how could anyone possibly resist the aroma of freshly made sweetmeats?

The auspicious times are the highlight of Avurudu. A lot of people view the auspicious times associated with the Avurudu with disdain in this high-tech age, but they teach us the value of time and punctuality. They also emphasise the importance of familial links. When practically everyone kindles the flames of the hearth at the same time, that sets the tone for working on time for the rest of the year. The auspicious time for “Ganu-Denu” or transactions is another opportunity to renew our bonds within the family and even outside of it. Many banks give their customers an opportunity to engage in banking transactions at this exact time, bringing a touch of prosperity to their lives.

Incidentally, the word “Ganu Denu” loosely translates to “Give and Take”, which is an appropriate lesson for our lives. This points to the need for a bit of compromise in everything we do. The symbolic conduit for Ganu Denu in Sri Lanka (as well as in neighbouring India) is the humble sheaf of betel leaves, called Nagawalli in ancient times. There are many legends associated with the betel leaf which has become a pivotal item in New Year festivities. The betel leaf also symbolises our close affinity with Nature. It is thought of as a harbinger of prosperity.

It was amazing that an entire village (and indeed an entire country) could do one thing at exactly the same time. We would visit the temple, attired in white, during the nonagathaya (Punya Kaalaya or period for meritorious deeds). Then came the lighting of the hearth, which was a family affair, followed by another, even more important family affair – the partaking of meals.

A joyous occasion

Farmers and those who were employed also left for work at an auspicious moment, a couple of days later. Needless to say, Avurudu was easily the most joyous occasion of the year, heralded by the lighting of crackers and the beat of rabanas amidst a profusion of erabadu flowers.

But the villagers often saved the best for last – the annual Bakmaha Ulela (Avurudu festival) replete with traditional games such as pillow fighting, climbing the greasy pole, bun eating, cart racing etc and some modern ones such as cross country running. The village lasses got an opportunity to become the Avurudu Kumari. Incidentally, the Bak Maha Ulela has survived largely intact through the years, albeit with a heavy dose of sponsorship and commercialism.

Perhaps the best part of Avurudu was not the festivity per se – it was the spirit of giving and forgiving. Animosity was cast away in place of friendship. Enemies became friends. People vowed to give up discord and rancour.

That was bigger and better than even the sheer joy of Avurudu itself. Visits to friends and relatives near and far strengthened lifelong bonds.

As we celebrate yet another Sinhala and Hindu New Year, it is time we went back to these basics, these simple pleasures of life.

These are simple things that made Avurudu special for both children and adults all over the country. They still have the potential to do so.

We should be able to see through the veneer of commercialism and extract the essence of Avurudu so that future generations could still benefit from time-honoured traditions which we have inherited from our ancestors. Avurudu once again needs to be the simple celebration of spontaneous joy that it used to be.