Some connections are not made—they’re remembered. Ours was born not in words, but in shared reverence, mutual curiosity, and a faith that transcends sea and stone.

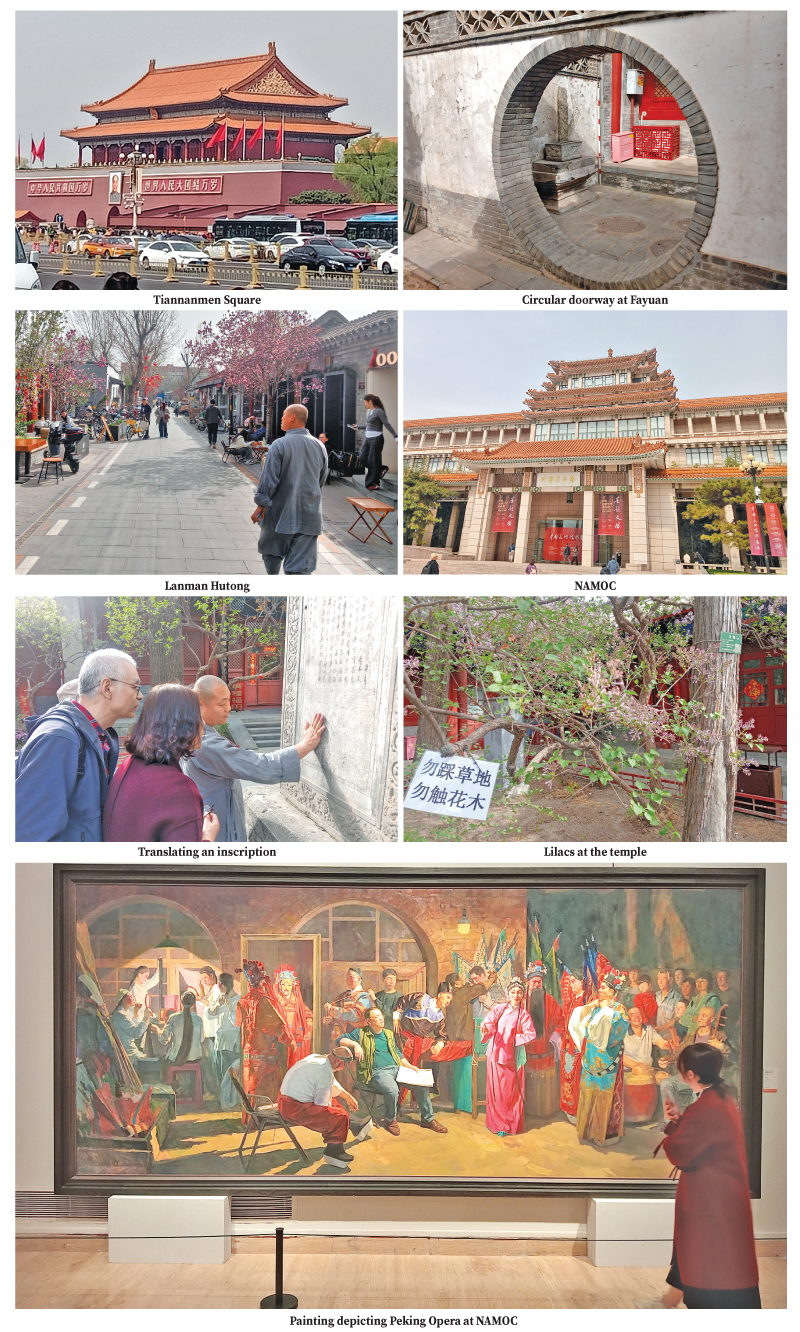

The golden sun of Beijing dazzled the Gate of Heavenly Peace. Outside, huddled masses waited patiently to pay respects to the hero of China. I took a picture and slid my phone back inside my pocket.

The golden sun of Beijing dazzled the Gate of Heavenly Peace. Outside, huddled masses waited patiently to pay respects to the hero of China. I took a picture and slid my phone back inside my pocket.

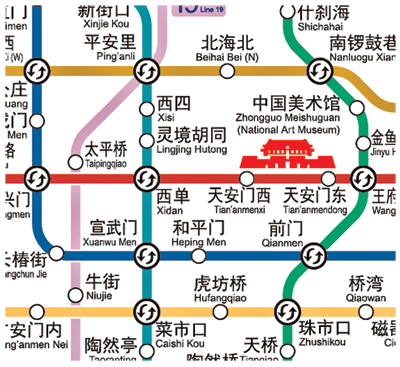

Tiananmen Square gets hundreds of thousands of visitors each day. However, due to the sheer influx, the Chinese authorities have mandated that visitors book their request prior. This can be done via WeChat – the “super app” of the People’s Republic. I couldn’t book a visitation due to my tight seminar schedule, so instead I walked east to Wangfujing station and rode the subway to the National Art Museum of China (NAMOC), costing me three yuan.

The security guards outside the museum asked me: “Did you register?” Mind you, all of these conversations were done via translation apps. However, to my relief, they scanned my passport and wave me in.

Art Museum

NAMOC had several exhibits on the day I visited. The first floor featured three shows – the Year of the Snake, Pierre Carron’s donated works and Beauty of the Five Great Mountains. The Year of the Snake and Mountains exhibit featured cultural artefacts including watercolours, ink paintings and calligraphy from several dynastical eras.

NAMOC had several exhibits on the day I visited. The first floor featured three shows – the Year of the Snake, Pierre Carron’s donated works and Beauty of the Five Great Mountains. The Year of the Snake and Mountains exhibit featured cultural artefacts including watercolours, ink paintings and calligraphy from several dynastical eras.

NAMOC’s halls were spacious and reminded me of the expansive spaces inside the BMICH – a recurring theme in Chinese State buildings. What you do notice immediately is the generous use of vermillion everywhere, which is a very auspicious colour according to Chinese culture.

The exhibit on the second floor – Beauty in Life featured sculptures and paintings from contemporary artists based on life in modern China. A striking canvas – depicting scientists flying a drone to collect research data bore striking resemblance to the era of Soviet-realism.

Ascending to the third floor, I felt suddenly at home. Buddha statues and Buddhist temple art dotted the corridors. The Ink Splendour and Cultural Context: Gansu Silk Road Art Treasures Exhibition presented an array of religious art from icons to bone scripts to mandalas. Gansu is a north-central Chinese province between Xinjiang to the West, Inner Mongolia to the East and Sichuan to the South.

Historically, the state of Qin (pronounced ‘Ch’in’) which established the first imperial dynasty in Chinese history originated in what is now south-eastern Gansu. The Northern Silk Road ran through the Hexi Corridor, passing through Gansu. Buddhism entered China via the Silk Road over 2000 years ago as bihikkhus travelled with merchant caravans.

Meeting Zhengliang

After circling around the exhibits and buying some items at the gift shop (Which included a limited edition Qi Baishi pack of playing cards) I stepped outside once again, to the streets of Beijing.

As I was wondering where next to go, I saw a happy Chinese Bihikkhu in sombre grey robes walking out of NAMOC. I hastily translated and showed on my phone: “Are you a Shaolin monk?” He smiled and typed back: “No, but I’m a bihikkhu at Fayuan Temple”. I asked him: “Can I follow you?” to which he winced. I was desperate: “We have a lot of Buddhist Temples in Sri Lanka”. His expression changed: “What a coincidence. I was in Sri Lanka this February!” I pressed on: “What city did you visit?” “Kandy,” was his reply. “That’s my hometown!” I beamed.

At the temple courtyard

At that moment we became friends. We walked to the subway station. I asked him if he spoke any English and he said he did a little. I later learned his name was Zhengliang.

I showed him the photographs of the Ghansu Silk Road exhibit at NAMOC and he smiled even more. We bought our tickets to Caishi Kou station which is due west on Line 7.

On our ride, he showed me the photographs from the same exhibit and I started talking about my love of Chinese culture and my favourite classic – the Journey West. The bihikkhu took his phone again and zoomed into one particular painting. On one of the cliffs stood the protagonists of Journey West – The Monkey King, the monk Xuanzang, Pigsy, Sandy and the White Dragon Horse.

Lunch time approached as we exited the station. I offered to buy food for the bihikkhu and he obliged. “Do you like rice or noodles?” he asked in English. “Noodles,” was my reply.

Zhengliang led me through a very beautiful street. Lanman Hutong is full of hip bars, cafes and gift shops selling souvenir magnets. The scent of brewed coffee and sizzling peanut oil danced between cherry blossoms and rooftops with flying eaves.

The Fayuansi neighbourhood, where the Fayuan temple is located is old-Beijing, the streets were narrower and cobbled. It was very ‘Feng Shui’ and reminded me of Galle Fort.

Scars and noodles

Ven. Zhengliang

We entered the noodle shop. Ven. Zhengliang said he was a vegetarian and ordered Changping noodles while I preferred a hearty bowl of pork noodles in hot soup. As we waited for our orders I asked him about the scars on his head and he quickly translated.

According to Chan Buddhist tradition, Jieba are an ordination practice where ritual burn scars are received by monks who take up the Bodhisattva precepts. Lay people usually get it on their arms. For bihikkhus, it signifies lifelong commitment.

When I tried to pay, I discovered he’d already done so—via QR Pay.

“Why didn’t you let me pay?”

“You are in my hometown,” he said gently.

Fayuan Temple

The Fayuan Temple (not to be confused with the bihikkhu Faxian). The temple was first built in 645 during the Tang dynasty by Emperor Taizong. The temple houses a collection of Tibetan texts and priceless Buddhist icons including statues and paintings of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara and Guanyin the Compassionate.

Ven. Zhengliang told me that the temple’s lilacs are especially popular and draw in many tourists in the spring. He showed me into the first shrine, lit up two joss sticks and handed two to me. I politely declined due to my Christian beliefs and he obliged by offering the incense himself.

He led me to the ante chambers around the main shrine and showed me the statues of the many abbots and Buddhist masters.

Beijing Transit lines

The next shrine also had several Buddha statues and the thousand-armed Avalokiteshvara. At this point I told him about my article on the cult of Avalokiteshvara worship in Sri Lanka during the 7th-10th Century (See Sunday Observer July 30, 2023).

From chamber to chamber he took me, showing centuries-old icons, some even 2000 years old.

We exited the shrines and walked around the yard. Several tourists approached the bihikkhu and asked him to translate an inscription on a stone stele. The local worshipers were curious about me and were delighted to know I was Sri Lankan.

As much as I wanted to linger, time was slipping away. I had to leave Fayuan Temple. But what lingered was the sheer improbability of this encounter—meeting Ven. Zhengliang in a city of over 22 million, more than the population of my entire country.

Some connections are not made—they’re remembered. Ours was born not in words, but in shared reverence, mutual curiosity, and a faith that transcends sea and stone.

Perhaps I’ll see the good bihikkhu again—and this time, I’ll bring him a gift from Sri Lanka. Until then, there’s always WeChat.