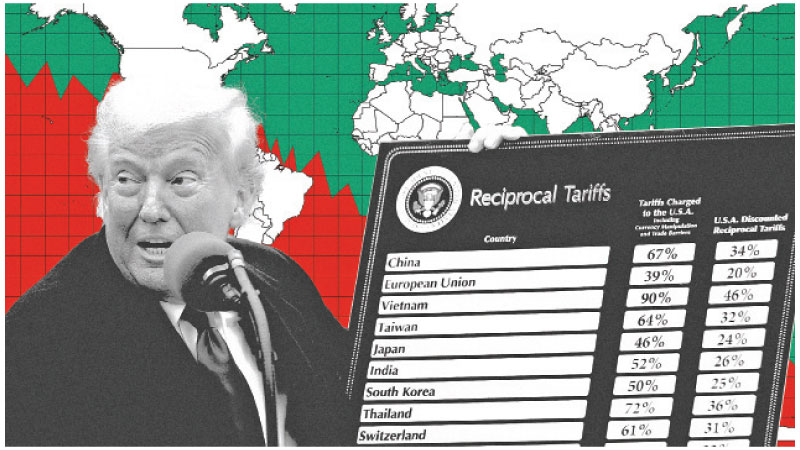

When Donald Trump assumed the U.S. Presidency in 2016, one of his key economic proposals was the introduction of a “reciprocal tariff” policy. Framed as a solution to America’s long-standing trade deficits and economic “unfairness,” this policy allowed the U.S. to impose the same tariff rates on countries that tax American exports. Trump’s justification is that the move is a way to level the global trade field and bring manufacturing jobs back to the U.S.

When Donald Trump assumed the U.S. Presidency in 2016, one of his key economic proposals was the introduction of a “reciprocal tariff” policy. Framed as a solution to America’s long-standing trade deficits and economic “unfairness,” this policy allowed the U.S. to impose the same tariff rates on countries that tax American exports. Trump’s justification is that the move is a way to level the global trade field and bring manufacturing jobs back to the U.S.

In his second term, Trump has already announced new tariff rates targeting many countries, including Sri Lanka. Although the original focus was China, now poised to overtake the U.S. as the world’s largest economy, nations such as Sri Lanka have also been caught in the fallout of these abrupt policy moves.

However, Trump has been forced to scale back some of his tough positions. Despite continuing with strong rhetoric, pressure from both domestic and international fronts has led to clear signs of retreat.

Breaking the rules of engagement

Trump’s tariff strategy marked a major departure from decades of multilateral trade diplomacy. His approach shifted from cooperation through frameworks such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) to a more transactional model: if Sri Lanka taxes U.S. cars at 100 percent, the U.S. will do the same to Sri Lankan goods.

While this move resonated with frustrated U.S. manufacturers, it alarmed global markets. The threat of a global trade war loomed large. Trump’s strategy disrupted supply chains, challenged WTO authority, and caused tit-for-tat retaliation from China, the European Union, Mexico, and Canada. These decisions often shifted without consistent policy rationale, heightening market uncertainty.

The WTO promotes trade fairness through non-discriminatory rules like the Most-Favoured-Nation principle. Trump’s focus on bilateralism and retaliation bypassed these principles. This undermined WTO authority and encouraged similar unilateral actions by other nations.

He often cited national security under Section 232 of the U.S. Trade Expansion Act to justify tariffs on steel, aluminum, and automobiles. Many saw these justifications as politically driven rather than genuine threats. Using this loophole risked normalising protectionism under the guise of security.

Trump also crippled the WTO’s dispute resolution by blocking appointments to its Appellate Body, rendering it non-functional by 2019. Without this enforcement tool, countries lost a legal avenue to address trade issues. This weakened faith in the global trade system and pushed countries towards alternative agreements.

While President Biden aimed to rebuild trust in global institutions, the damage from Trump’s approach lingers.

Supply chain disruptions

Trump’s tariff policies during the U.S.-China trade war severely disrupted global supply chains. Tariffs on billions of dollars of goods forced companies to rework sourcing strategies and manufacturing sites. U.S. firms relying on Chinese parts faced higher import costs, prompting a shift to countries like Vietnam, Mexico, or India. But such moves were costly and time-consuming.

This impact spread globally. Southeast Asian economies integrated into U.S.-China supply chains struggled to adjust. Companies built redundant supply chains to buffer future shocks, sacrificing efficiency and driving up prices. The once-optimised just-in-time model began to unravel, increasing economic volatility.

U.S. allies such as Japan, South Korea, Canada, and the EU were hit with tariffs despite strong political ties. Tariffs on steel, aluminium, and autos, often under the pretence of national security, strained long-standing relationships.

The EU, historically aligned with the U.S., began exploring stronger trade ties with China and Russia. This shift marked a loss in U.S. credibility as a stable partner. Strategic alliances began to realign.

The China-U.S. rivalry deepened. What started as a trade dispute evolved into a broader competition over technology, finance, and military dominance. China accelerated its Belt and Road Initiative, while developing nations found themselves navigating between two superpowers.

Trump’s tariff-first approach weakened global cooperation mechanisms. Treating all nations as economic rivals fostered zero-sum thinking, reducing diplomatic coordination on shared issues like climate change and cyber threats.

Domestic legal rebellion

Trump’s across-the-board 10 percent import tariff and higher rates for specific countries, especially China, triggered legal action. States and businesses challenged the tariffs as unconstitutional and economically harmful.

A coalition of 12 Democratic Attorneys General, led by New York AG Letitia James, filed a lawsuit arguing Trump lacked authority to impose tariffs without Congressional consent. California Governor Gavin Newsom and AG Rob Bonta launched a separate suit, challenging the use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), saying trade deficits don’t qualify as national emergencies.

Small businesses, represented by the Liberty Justice Center, also sued, calling the tariffs illegal and imposed without public input. They said the IEEPA had never been used this way and that Trump’s actions overstepped executive power.

These lawsuits question both the constitutional basis and economic logic of Trump’s tariff policy, with possible long-term effects on how trade policy is governed in the U.S.

Despite Trump’s claim that “China is paying the tariffs,” studies from the Tax Foundation, Brookings, and Harvard reveal the truth: U.S. importers pay, and costs are passed on to consumers.

Trump’s tariff policy drives up prices for goods from electronics to furniture. Households are estimated to pay an extra $700 to $1,000 annually. Manufacturers, especially those using imported materials like steel and semiconductors, also face higher costs. These are either passed to consumers or offset by job cuts.

Product variety in the U.S. market may shrink as foreign firms cut exports due to retaliation. Domestic producers, facing less competition, may raise prices, further burdening consumers. Washing machines, for instance, recorded a 20 percent price hike after Trump’s 2018 tariffs.

Small businesses reliant on imported parts suffer more, as they lack the bargaining power to absorb costs. Many face closure or are forced to raise prices.

U.S. exporters—especially farmers and manufacturers—lose markets due to foreign retaliation. This leads to layoffs and reduced income, compounding the impact on consumers.

To soften the blow, the Government has paid billions in subsidies to affected sectors, notably farmers. These funds are taxpayer-funded, meaning Americans pay at stores and through taxes.

Stubborn Trump

Trump remains firm, framing reciprocal tariffs as a needed correction for “decades of unfair trade.” His stance fits his “America First” ideology and appeals to voters in key manufacturing states.

He distrusts institutions such as the WTO, seeing them as favouring foreign competitors. Tariffs serve as a hardball tactic to gain better terms and signal strength.

He dismisses expert economic advice, preferring anecdotal support from sympathetic business owners. Reversing course would contradict his image and alienate his base.

Trump’s political survival hinges on projecting consistency and toughness. Even if tariffs bring hardship, he views them as necessary and refuses to compromise.

Trump’s tariff policies benefited certain groups: domestic steel and aluminum producers, lobbyists, law firms, exempted countries, and political allies. However, these gains were narrow.

The losers include consumers, farmers, exporters, small businesses, and U.S. allies. Manufacturing—a sector Trump sought to protect—also suffered from higher input costs.

Though “reciprocal tariffs” sound fair, global trade is more complex. Developing nations often need higher tariffs to protect young industries. Trump’s approach ignored these nuances.

Trade fairness involves more than equal tariffs—it includes context, subsidies, standards, and quotas. Trump’s narrow bilateralism clashed with multilateral trade norms, appearing punitive rather than equitable.

Implications for Sri Lanka

Though not a major U.S. trade partner, Sri Lanka is feeling the ripple effects. Global supply chain shifts away from China could have benefited Sri Lanka, but political instability and weak infrastructure have held it back.

Sri Lanka relies heavily on exports—garments, tea, rubber, and services. Disruptions in global demand affect these sectors. For instance, if U.S. tariffs reduce access for European or Asian firms, they may cut orders from Sri Lanka.

Job losses are a real threat. The apparel industry, which employs hundreds of thousands, faces falling orders and tight margins. Layoffs and factory closures could follow. Related sectors like logistics and packaging would also suffer.

Reduced consumer spending in the U.S. due to higher prices hurts Sri Lankan exporters. Lower demand affects foreign reserves and the balance of payments.

Service exports such as IT and Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) may also shrink. If U.S. and EU companies tighten budgets, they reduce outsourcing, affecting employment for skilled Sri Lankan youth.

Financial volatility from tariff wars could lead to capital flight from Sri Lanka, currency depreciation, and higher borrowing costs. This is especially risky given Sri Lanka’s current economic challenges and reliance on IMF support.

Trump’s unpredictability in trade policy adds to global uncertainty. For Sri Lanka, this complicates long-term trade strategy and forces constant reassessment of markets and partners.

While diversification could help, shifting away from traditional Western markets will take time. In the interim, Sri Lanka must navigate the unstable global trade climate shaped by Trump’s tariffs.