Reading through the artists’ concept notes, the exhibition catalogue, talking to people who had seen it, and seeing literally hundreds of digital photos of the ongoing exhibition, ‘Witness(eth)’ at the Galle Face Hotel, two often flagged ideas of what it means to witness came to my mind. One is Elie Wiesel’s argument that “for the dead and the living, we must bear witness.”

The other is Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra observation, “Truth, whose mother is history, who is the rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past, example and lesson to the present, and warning to the future.” A singular idea that becomes clear in both Wiesel’s and Saavedra’s words is, witnessing as an act is not merely a matter of seeing. It is also an emotional burden impregnated with an idea and expectation of telling. That is, telling in times to come so what was witnessed is revealed.

As most people would know, the word, ‘witnesseth,’ the title and the theme of the exhibition, is simply legalese for ‘witnessing’ while in its legalistic rendition the word gives much more linguistic weightage to the act of witnessing or seeing. ‘Witnesseth’ is the second edition of an annual series of exhibitions presented by a group of artists calling themselves The Collective. But as their catalogue notes, The Collective uses the word in a self-consciously nuanced way to mean to “‘take notice of’ and “to bear that knowledge, and then to reveal.”

In this sense, to witness is not only a private or public act of seeing, but also a responsibility to publicly articulate what is seen. Through this sensibility, the theme of the exhibition comes close to the idea of witnessing encapsulated in the ideas of people like Saavedra and Wiesel. For The Collective, witnessing is a burden to carry that one needs to find means to reveal. The exhibition is one way of revealing.

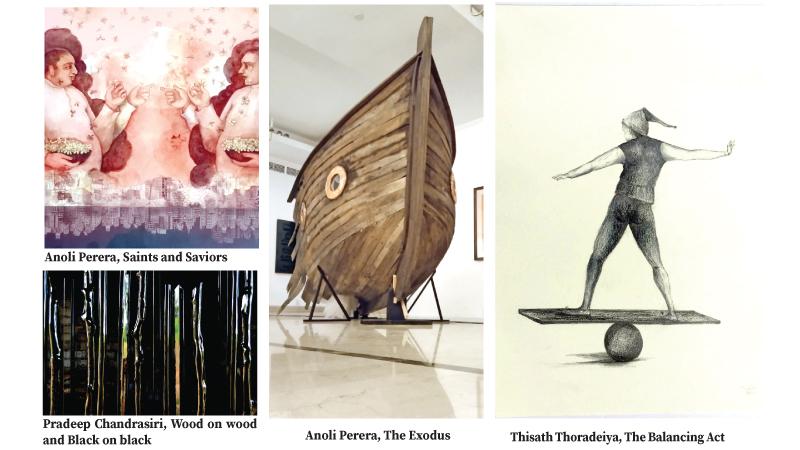

The Collective consists of Pradeep Chandrasiri, Mahen Perera, Anoli Perera, Pala Pothupitiye, Koralegedara Pushpakurmara and Thisath Thoradeniya who are arguably among Lanka’s senior and more creative artists active at present. But it is a risk to talk about the work of a group of artists who are also friends.

Political importance

But my interest in writing about their work stems from the fact, despite the sensibility of witnessing the theme of the exhibition connotes and its crucial political importance in present times, it is almost invisible in the local discourse of art. Not too many people know it is happening in Colombo, mostly due to what appears to be poor public engagement on the part of the artists and the sponsors, which is truly unfortunate as it is a remarkably powerful and creative exhibition. That is, powerful politically and creative in terms of its visual language and engagement with material.

The artists ask in their catalogue, “how does one take this cognised depository of memory” acquired from the act of witnessing “to the future, a future that seems intensely fractured and no different from its past?” In a sense, the exhibition is an effort at making this process possible in so far as the artists’ individual and collectivememories are concerned. But it can only be a more serious public engagement with a broader public memory and collective witnessing, if there is public engagement with the exhibition and its visual politics.

Pradeep Chandrasiri’s paintings, mostly executed on black surfaces and installations, also in black, deals with the issue of what one does after witnessing, particularly in the context of local and global politics of power and violence. He poses the question, “is this a dark prediction, or a prophecy about the aftermath of this ‘quiet social moment?”

For him, witnessing without the power to affect change, is a matter of seeing “silently, like a blind man.”He deals with this unenviable situation via a “self-imposed paralysis” to take his thinking beyond this powerless silence. But that effort pushes him over the edge “towards melancholia.” As he explains, “I try to grasp the blackness, but the blackness blinds me even more.”

So, his works in the exhibition are attempts at dealing with the afterlife of witnessing and placing in context his movement towards melancholia precisely because he, as an individual and many others in society cannot affect change taking what they witnessed as their point of departure. That is, they have seen, but do not have adequate power to transform. However, it does not mean that one cannot articulate, and that is precisely what Chandrasiri and others are trying to do in the exhibition.

Mahen Perera’s works are collectively called ‘Rivers of Stain’. They consist of objects presented in different ways, which the artist sees as a “a journey into the grounds of materiality,” which “refigure the psychonomy of one’s corporeal being as tangible formations which exist as testimonies of an illusive narrative.”

That is, at one level, these objects can be understood as the residue of the aftermath of an incident, which the artist or the society may have witnessed. But they – be they limbs; remnants of household items or whatever – tend to be part of an elusive narrative because like in any history, no testimony is complete, but afragment that can only tell a partial story or a partial truth of the past at best.

Like Chandrasiri, he too is trying to articulate the difficulty in narrating in the aftermath of witnessing though at the same time he is also trying to articulate it in his own code. Whether viewers can decipher his code without the artist being present is another matter.

Pala Pothupitiye is more directly interested in the idea of history and his work is less coded compared to Chandrasiri and Perera. As he notes, “I am fascinated with history and historical artifacts.” And he says, “both history and historical artifacts are residues that constantly impact our thinking, our movement and our sense of belonging in the present.”

But, very self-consciously he is suspicious of mega-histories – be they of nations or communities – because they often contradict what he has witnessed as a person and as a member of society. So, his interest in recent works and in this exhibition is not in mega histories of glorious pasts, but in “the underbelly of such ‘glorious’ encounters within history to find the counter narratives of the ‘disgraceful’ and ‘dishonorable’ foundations of those glorified histories.” In other words, he is more interested in dealing with the act of witnessing head on and without too much coding in his presentation, and also without succumbing to melancholia or falling prey to feelings of powerlessness.

Koralegedara Pushpakumara strongly believes that people cannot live their lives in isolated from their personal experiences, memories, and their personal histories. That is, how they see and feel the world will depend on what they are in terms of these trajectories of life. Witnessing and particularly narrating what is seen is also formulated based on this background.

Different people will narrate what they have witnessed differently or decide not to reveal at all based on how their personalities are constructed. Though Pushpakumara’s work is quite abstract in the same sense as Mahen Perera’s and Chandrasiri’s, Pushpakumara believes that they are replete “with meaningful signs” so that what he is trying to narrate can be deciphered by viewers because, though “one’s memories are very personal initially,” “they also have the potential to be public.”

This is because experientially, one’s memories may be that of the collective as well. This is why, if the act of witnessing leads to the narrativisation in the public domain, its authorship might be shared my many albeit often in silence. Pushpakumara seems to bank on this possibility to make his works meaningful to others.

Anoli Perera’s work in the exhibition is generally anchored to the idea of exodus often consequent to manmade calamities from war to politics of exclusion. As she notes, “human feet moving in unison” attempt to “find the next land of promise, to give genesis to their lost dreams.”

But that exodus, usually following close behind not simply to acts of witnessing but also of experiencing calamities does not always end in finding a promised land. Instead, that kind of exodus can also mean the sudden and violent end of large groups of people long before any semblance of a promised land or a stable future is found.

For Perera, authors of calamities are generally political figures who tout themselves as popular leaders, religious personalities and so on who have the ability to use their charisma to fool masses of humanity everywhere. While normal people may perish or experience extreme pain in these calamities resulting in exodus, the authors of such disasters – like politicians –usually escape such political trajectories.

Golden land

As she notes, “the history that touted a golden land, a replica of the same promised by the saviours bearing milky white attire, perfumed with flowers stand still, unmoved and unperturbed by the storm ashore.” For her, as in the case of Pothupitye, history is important mostly as a means of excavating its large chunks of silence and erasure.

This is what she means when she says, “We witness a world that we have little control of. We watch in paralysis the history distorted, mythology industrially manufactured, humanity suspected, and cities crumble to dust.” Her work is meant to unmask the culprits of catastrophes and push to the public sphere hidden and unpleasant histories.

For Thisath Thoradeniya, like the other artists of The Collective, “witnessing is an inherent activity of our bodily existence, and our conscience determines our act of memorising.” For him, even personal memories are incomplete as they too lose their cohesiveness and select specific contents as opposed to others in the process of memorialisation. This selectivity and conscious erasure is a necessary part in the process of individual survival. In this sense, memory post-witnessing too is a selective process and never a complete canvas of the past.

Seen on this sense, what The Collective has attempted to do is to bring the idea of witnessing and narrating what is witnessed to the public discourse of recent history and contemporary art. But that attempted process will only be complete if the public can engage with both the exhibition and its visual langue on one hand and the broader local and global politics it is attempting to narrate on the other. Since the exhibition will be on May 31, 2023, I hope more people will opt to see it and would attempt to engage with its ideas as they would make historical sense to all.